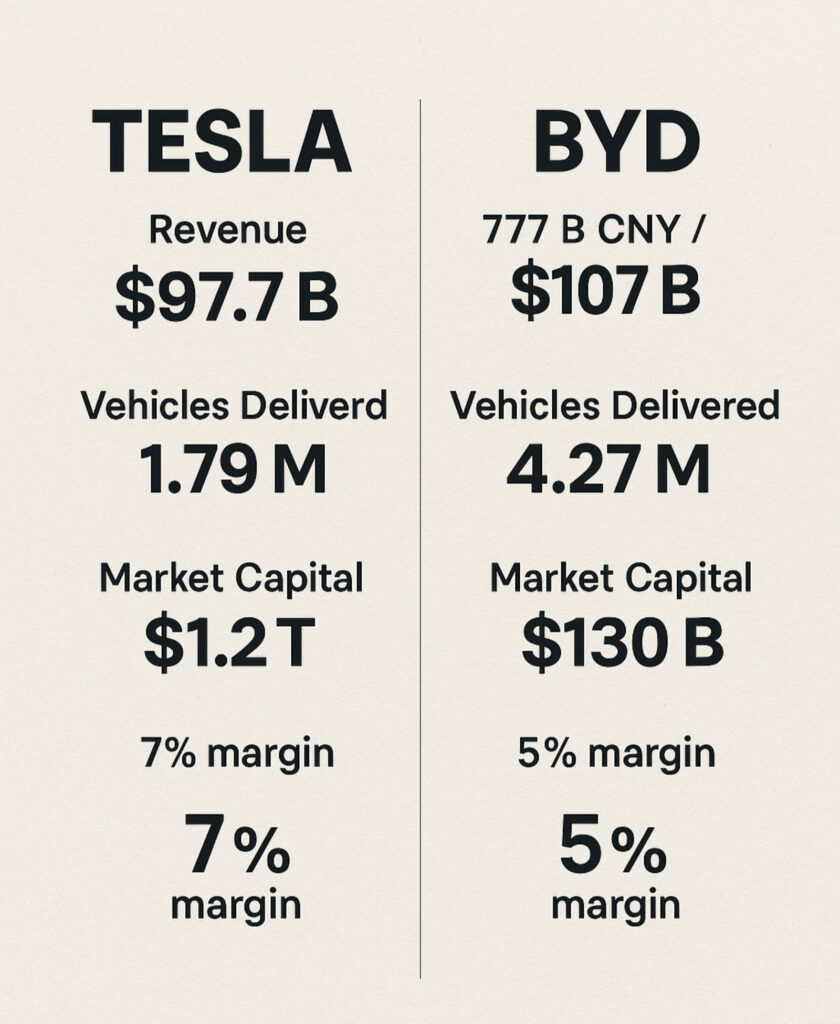

Electric vehicles have become the battleground for the world’s biggest automakers, and two names loom largest: Tesla and China’s BYD. On the surface, the numbers paint an astonishing story. In 2024 BYD – backed by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway and riding surging demand at home – reported roughly 777 billion yuan (about $107 billion) in revenue, surpassing Tesla’s $97.7 billion for the year. BYD also built far more vehicles (over 4.3 million plug-in cars and hybrids versus Tesla’s ~1.79 million EVs). Yet in the stock market, Tesla’s valuation dwarfs BYD’s. Tesla’s market capitalization is on the order of $1.2–$1.3 trillion (mid-2025), roughly ten times BYD’s ~$130 billion. How can Tesla command such a premium, despite BYD’s comparable or even superior sales and top-line growth?

This puzzle can only be solved by looking beyond the raw figures. On Wall Street and in the press, narrative, perception and leadership aura often count for as much or more than quarterly earnings. Elon Musk – a boundary-defying tech billionaire and master marketer – has built Tesla’s image into something far grander than an auto company. His promises of electric robo-taxis, full self-driving technology, and energy innovations fuel a “future of mobility” story that investors buy into. In contrast, BYD’s remarkable achievements – its integrated manufacturing, rapid sales growth and homegrown technologies – are less well known outside Asia. Many Western investors still view BYD as simply a Chinese carmaker, subject to geopolitical risk and harder to bet on. Add to this a thicket of policy quirks (tariffs, tax credits and subsidies favoring local production) and market psychology, and the valuation gap begins to make sense.

In this deep dive we unpack the facts and the sentiment: comparing 2024 financials, examining product pipelines, and probing how CEO charisma and national policy tilt the scales. The story of Tesla vs. BYD isn’t just about cash flows and production numbers – it’s a case study in how investor psychology and branding can trumpet one company’s outlook over another’s stronger balance sheet.

2024 Financials: Revenues and Profits

In the latest fiscal year both Tesla and BYD posted record-breaking results – but in very different ways. BYD’s total revenue for 2024 jumped about 29% year-on-year to roughly 777.1 billion yuan (≈$107 billion). Tesla’s revenue was also up slightly – about $97.7 billion, just a 1% increase over 2023. Thus BYD finally overtook Tesla’s top line for the first time (BYD had been a few billion above Tesla in Q4 2024). The difference largely reflects BYD’s explosive domestic growth, while Tesla’s sales plateaued as the company scaled globally.

However, Tesla remains more profitable on each dollar of sales. Tesla earned about $7.09 billion in net income for 2024, a net margin of roughly 7.3%. BYD’s net profit was about 40.3 billion yuan (~$5.6 billion), a margin of only ~5–6%. In other words, Tesla banked a larger slice of profit per dollar of revenue. (Tesla’s profitability suffered in late 2024 as it cut prices – its full-year net income was down sharply from ~$15 billion in 2023 – but BYD’s profit margin is still lower due to its mix of models and businesses.)

Key 2024 metrics illustrate the contrast:

- Revenue: Tesla ~$97.7 B; BYD ~$107 B.

- Net Income: Tesla ~$7.1 B (7.3% margin); BYD ~$5.6 B (~5.2% margin).

- Sales Growth: Tesla +1% YoY; BYD +29% YoY (reflecting China market demand).

- Vehicles Sold (2024): Tesla ~1.79 M EVs; BYD ~4.27 M plug-in vehicles (≈1.8 M BEVs + 2.5 M plug-in hybrids).

- Market Cap (Sept 2025): Tesla ~$1.2–1.3 trillion; BYD ~$130 billion – roughly an order of magnitude larger for Tesla.

- Valuation Multiples: Tesla trades on eye-watering multiples (often 50–100x forward earnings or more); BYD’s P/E is in the teens.

These raw numbers underscore the puzzle: on sales and volumes BYD is as big or bigger, but Tesla is far more profitable per unit and sits on a stratospheric valuation. Any rational investor looking solely at fundamentals might argue that BYD is a screaming value, or that Tesla is overpriced. But valuations are heavily shaped by expectations and sentiment.

Production Volumes and Market Share

The scale of BYD’s operations far exceeds Tesla’s when you count all plug-in vehicles. In 2024 BYD built or sold roughly 4.27 million new-energy vehicles globally. By comparison, Tesla delivered about 1.79 million vehicles (nearly all battery EVs) that year – a slight decline from 1.81 M in 2023. (Tesla’s production was about 1.77 M, roughly matching deliveries.) In fact, BYD’s 4.27 M included ~2.51 M plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) and ~1.76 M pure EVs. Had BYD only counted full EVs, it would have been neck-and-neck with Tesla.

Global EV market share: BYD now looks like the world’s largest EV maker. Industry data show global battery and plug-in hybrid sales around 23–24 million units in 2024. BYD’s 4.27 M total (BEV+PHEV) was on the order of 18% of that market. Tesla’s ~1.8 M EVs were around 7–8% of global EV sales – still leading any individual legacy automaker but well behind BYD. (Tesla’s share of pure BEVs was larger – BYD sold 1.76 M BEVs, just shy of Tesla’s 1.79 M, because Tesla sells only pure EVs.) In practice, “who is #1” depends on definitions, but one recent analysis notes BYD overtook Tesla in EV sales during 2024 and remains on a higher growth trajectory.

China vs. U.S. dominance: The market shares break down very differently by region. In Tesla’s home market, the U.S., Tesla is king of EVs: as of early 2025 it had roughly 50% of U.S. plug-in sales, more than any competitor. BYD, like other Chinese brands, is effectively absent from the U.S. market (more on why below). In China, by contrast, domestic brands dominate EV sales. About two-thirds of Chinese EV buyers choose local makes. BYD is among the leaders in China’s vast NEV (new-energy vehicle) market, responsible for perhaps 20–25% of domestic NEVs in 2024, whereas Tesla’s market share in China was only about 6–7%. Tesla’s Shanghai factory kept it a player, but it never cracked the market as strongly as BYD or other homegrown names.

Global reach: Tesla has been aggressively global: it has factories in the U.S. (Fremont, California and Austin, Texas), China (Shanghai) and Germany (Berlin), plus sales operations worldwide. BYD, on the other hand, has only recently begun expanding beyond China in force. In 2024 roughly 20–30% of BYD’s sales were outside China. BYD is building or planning new plants in Hungary, Thailand, Turkey and Brazil (for cars and even for electric trains), and has launched models in Europe and Asia. But in 2024 the lion’s share of BYD’s deliveries were still in Greater China.

By contrast, Tesla sells significant volume in North America, Europe and China. Tesla’s U.S. dominance and strong performance in Europe (especially for the Model 3/Y) give it substantial geographic balance. BYD is gradually going global, but even Tesla officials admit that Chinese EV makers could penetrate richer markets only slowly due to regulations and brand awareness.

In summary: BYD has ramped up production far beyond Tesla’s, thanks especially to its plug-in hybrids. But Tesla remains most prominent in the Americas and Europe, and benefits from being the incumbent EV leader worldwide just a few years ago.

Technology and Product Lines

Both companies tout innovation, but in very different styles. Tesla built its reputation on breakthrough tech and hype. Its vehicle lineup is relatively simple: today that’s the Model S and X (luxury sedan and SUV), the mass-market Model 3 sedan and Model Y SUV, and now the highly anticipated Cybertruck (a futuristic electric pickup that began production in late 2023). Two more models are (or were) on the horizon: the Semi electric truck (aimed at fleets) is slated to start deliveries in 2025 or 2026, and the revised Tesla Roadster sports car is also long-awaited. Crucially, Tesla has for years promised a “robo-taxi” – a fully autonomous ride-hailing vehicle – based on its full self-driving (FSD) software. Musk has repeatedly moved the timeline (now aiming for 2025), keeping investors enthralled even as the technology faces delays and regulatory scrutiny.

Beyond cars, Tesla has a large energy business. It sells home batteries (Powerwall), large industrial batteries (Megapack), and solar panels/tiles. In 2024 about 15–20% of Tesla’s revenue actually came from energy generation and services (solar, batteries and regulatory credits). Tesla also rakes in “regulatory credits” by selling emission credits to other automakers. This segment has padded Tesla’s profits in past years. On the software side, Tesla heavily promotes its Autopilot and FSD systems – sophisticated driver-assist features with AI software at their core, which it hopes to eventually commercialize as fully autonomous driving.

Tesla’s product narrative is high-tech: battery innovation (e.g. 4680 cells), AI, self-driving, even Neuralink-like brain-computer stuff in association. Musk’s public flair — testing rockets with SpaceX, launching satellites — bleeds into Tesla’s “mission” to accelerate the future. Tesla spends relatively little on traditional advertising; instead it relies on Musk’s persona, social media buzz, and a premium brand image (“it’s what the future looks like”).

BYD’s approach is more pragmatic and broad. BYD stands for “Build Your Dreams” and it has a dizzyingly diverse lineup. Among passenger vehicles, BYD sells multiple electric sedans and SUVs (models like Seal, Dolphin, Han, Yuan, Tang, Atto 3, etc.) alongside a wide range of plug-in hybrids (Toyota-co-developed DM-i and DM-p series, or Denza models in China). Unlike Tesla, BYD’s EVs range from budget-friendly city cars to premium models, and it integrates hybrid drive systems that let a car switch between gasoline and electric. BYD’s hybrids give it a big edge in markets where pure EV subsidies are waning or where drivers want longer range.

Technology-wise, BYD touts its vertical integration. It manufactures its own batteries (including the breakthrough “Blade Battery” for safety and efficiency), electric motors, and even chips. It also makes a range of commercial vehicles (buses, trucks, forklifts) and is active in rail transit (BYD Rail produces driverless urban rails). BYD comes from battery-making roots and still assembles components for mobile phones (some 20% of BYD’s revenue in 2024 came from handset assembly and electronics). It invests heavily in R&D – in 2024 BYD reportedly spent around 54.2 billion yuan on research (≈$7.7 billion), far outpacing Tesla in absolute terms. BYD’s labs work on advanced hybrid powertrains (like the fifth-generation DM system), ultra-fast charging, and new architectures for EVs (e-Platform 3.0, Super e-Platform, etc.).

In short, Tesla’s innovation pipeline is built around transformational bets – full autonomy, radical new vehicle concepts, software updates over the air – whereas BYD’s innovations focus on industrial strength and efficiency – scalable production, safer batteries, and continually updated model families. Both have ambitious roadmaps (Tesla’s robo-taxi vs. BYD’s next-generation plug-in hybrids), but Tesla is seen as the visionary innovator, BYD as the engineering execution champion.

Geographic Reach and Government Support

Location matters. Tesla is headquartered in California and listed on the U.S. stock market, which gives it a home-field advantage with many investors. It has four major vehicle plants: Fremont (USA), Shanghai (China), Berlin (Germany), and Austin (Texas), plus a battery plant in Texas. These plants supply North America, Europe and Asia. Importantly, Tesla benefits from local incentives. Under the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), buyers of Tesla cars assembled in North America can get up to a $7,500 tax credit – directly supporting Tesla’s sales in the U.S. and Canada. Tesla also avoided major tariffs: its cars made in Shanghai face no extra duty selling back into China, and its U.S.-made cars have no China-related tariffs either. Europe offers EV incentives too (often tied to local production content), and Tesla’s Berlin factory is set to supply more of Europe going forward.

BYD, in contrast, is based in China and trades in Hong Kong and Shenzhen. China’s government has strongly backed EV adoption: generous subsidies in early 2010s, quotas and license plate lotteries favoring new-energy cars, and massive investment in charging networks. These policies helped BYD grow rapidly at home, and Chinese consumers now largely prefer domestic brands. BYD’s business benefited from preferential treatment, though some consumer subsidies have wound down by 2024. Still, the Chinese market (over half of the world’s EVs) remains tilted toward homegrown companies – local brands now claim roughly two-thirds of all Chinese car sales, squeezing out foreign entrants.

However, BYD’s access to foreign markets is more limited. Most U.S. and Canadian government policy now effectively bars Chinese EVs. In 2024 the Biden administration raised U.S. tariffs on Chinese-made EVs (and batteries and components) up to 100% (building on Trump-era measures). In practice this meant BYD could not meaningfully sell its cars in the U.S. (one political report called Chinese EV imports an “extinction-level event” if they arrived unrestricted). At the same time, U.S. consumers get a tax break on Tesla and domestic EVs but not on imports, further insulating Tesla. In Europe, there are rising concerns about Chinese industrial subsidies and standardization; EU countries now impose about a 17% tariff on Chinese EVs, and have tightened rules on battery supply. BYD has started reaching Europe (a BYD Europe subsidiary in the Netherlands promotes exports, and assembly plants in Hungary and sales in places like Norway and the UK are ramping up), but these efforts are still young.

In short, Tesla sells where Western investors live, often at favorable tax rates; BYD mostly sells in China and parts of Asia. Both governments back their champions: Beijing sees BYD as a national star, Washington sees Tesla likewise. But the international trade rules tilt to Tesla’s benefit in the crucial U.S. and European markets, keeping BYD off equal footing.

Investor Psychology and CEO Cult

Even dry financial newspapers will admit it: Elon Musk is a phenomenon. He’s not just Tesla’s CEO; he’s a brand all by himself. Musk’s outsize presence – on social media, in the press, sometimes in courtrooms – means Tesla gets far more attention (and volatility) than BYD. Every new tweet or product reveal can move Tesla’s stock dramatically. For better or worse, markets latch onto Musk’s vision of the future: rockets, hyperloops, AI. Many investors see Tesla not merely as a carmaker but as a tech company at the nexus of transportation, software, and sustainable energy. That tech narrative commands premium valuations.

BYD’s leader, Wang Chuanfu, is comparatively obscure. BYD doesn’t run with the Silicon Valley style hype cycle. When it debuts a new model or battery, the news tends to stay in the business pages. As a result, BYD is often treated more like a traditional automaker or electronics contractor. Its stock tends to trade on fundamentals and industry news. Tesla’s stock is often swayed by stories: “Tesla to launch Robotaxi in 2025” or “Musk tweets about dogecoin” can influence sentiment, while BYD’s progress is digested more incrementally.

This psychological gap shows up in valuations. Tesla historically traded at extremely high multiples of sales and earnings. In early 2025 its P/E was often over 100 (even above 200 at one point), reflecting sky-high growth expectations. BYD, with slower growth rates but steadier profit expansion, trades in single-digit or low-double-digit multiples. Many U.S. mutual funds and retail investors overweight Tesla because it feels like a “growth tech” stock, whereas BYD (a Chinese manufacturer) has drawn less interest. Some analysts argue this discount is unwarranted – a “China discount” for fear of regulation or misreporting – but for now it persists.

Another factor: market sentiment and risk appetite. Tesla’s stock has seen manic swings: it soared during the EV hype of 2020 and 2021, then crashed nearly 30% in early 2025 when Musk’s attention wandered to social media (he ran Twitter in late 2022–2023) and Tesla’s China sales dipped. BYD, by contrast, has been a more stable gainer lately – its stock hit record highs in early 2025 as sales and earnings beat expectations. But even BYD’s surge attracted fewer headlines globally than Tesla’s volatility did.

In effect, Wall Street has built Tesla into a sentiment bellwether for EVs. Portfolio managers often say: “When Tesla sneezes, the whole EV sector catches a cold.” Tesla’s moves lead or lag sector ETFs, whether justified or not. BYD’s moves, especially its surging revenues, have been interpreted as part of a “China EV story” – but that narrative carries less weight among Western investors. Until BYD attains Musk-level name recognition, its stock will rely on rational analysis more than fairy-tale projections.

Perception, Branding and Side Businesses

Tesla’s brand cachet is enormous. Tesla drivers worldwide are often evangelists: their cars are seen as status symbols of innovation and green coolness. The sleek minimalist design and constant media buzz (cars on the Moon, on Mars, near the White House) create a halo effect. Even Tesla’s marketing is untraditional: it has no advertising budget but a cult-like fanbase that promotes it.

BYD’s brand is more grounded. In China it’s seen as a solid domestic champion – familiar to local buyers who grew up with its buses and early hybrids. Abroad, the BYD name is just starting to build recognition. It doesn’t carry the Tesla vibe of “this is the future.” Some Western consumers might still think “Chinese cars are cheap,” even though BYD is making very advanced vehicles and meets global safety standards. Chinese automakers in general face a long road to gain trust and prestige in Europe and the U.S. Investor bias can creep in, too: funds with mandates might avoid Chinese stocks for diversification or regulatory reasons.

On the other hand, BYD has diversified revenue streams that Tesla does not. In 2024 about 20% of BYD’s revenue came from non-automotive activities (handset components, assembly services, and electronics). Tesla has energy and service lines that accounted for roughly 21% of its 2024 sales. Tesla’s “other” products (solar, batteries, credits) are in many investors’ minds as future growth drivers, while BYD’s phone-related business is often overlooked by EV analysts. Both companies thus have sizable side hustles – but Tesla’s fit the Silicon Valley narrative better (clean energy, technology) than BYD’s (ODM manufacturing).

This branding and perception layer explains a lot of the valuation gap. Imagine two companies with roughly similar sales and growth, but one is a charismatic “future tech” leader and the other is a hardworking industrial giant. Investors will ascribe a premium to the former. Tesla’s CEO even once boasted that robotaxis and AI would push Tesla’s cap beyond $1 trillion. Whether those dreams come true or not, the speculation alone keeps Tesla’s multiple high. BYD, by contrast, is often discounted as the “boring but profitable” half of the story.

Geopolitical and Regulatory Context

Any analysis today has to consider geopolitics. Tesla and BYD operate in a world where U.S.–China relations are tense and governments vie for technology leadership. Chinese regulators often support local champions – for example, China continues to encourage EV adoption with infrastructure spending. BYD was designated a “strategic emerging industry” company in Beijing’s 13th Five-Year Plan years ago, and it benefits from such backing. Meanwhile, in the U.S. and Europe there is growing scrutiny of Chinese high-tech. BYD’s rise has prompted concerns: the U.S. sees Chinese EV companies as potential risks (spyware worries, or simply “made in China” data issues with sensors and software), while also wanting to protect its own automakers.

This context feeds into investor thinking. Some U.S. and European fund managers may hesitate to own BYD because they worry about “political risk” – for example, what if China curbs capital flows, or if Western governments further tighten exports of tech. Tesla, domiciled in the U.S., seems far less exposed to these geopolitical headwinds (beyond general market cycles).

At the same time, each company lobbies for beneficial policies. Tesla famously persuaded U.S. and local governments to allow it to directly sell cars (bypassing dealers) and receives large tax credits in many states. Musk and others have also made statements calling for or against certain regulations (like safety testing), which investors follow closely. BYD, for its part, has aligned with Chinese government goals (for instance, it pledged to stop making combustion-engine cars entirely) and has sought to work with foreign regulators as it expands abroad.

A final note on currency and financial access: Tesla is traded on the NASDAQ, fully accessible to most global investors. BYD’s primary listings are in Hong Kong (H-shares) and Shenzhen (A-shares), with an ADR in the U.S. (BYDDF) that trades thinly. Many Western investors cannot easily buy BYD, and those who can often do so indirectly (through ETFs or mutual funds). This limited accessibility can depress a stock’s valuation too; in effect, Tesla’s investor base is larger and more enthusiastic.

How Market Cap Leaves Numbers Behind

By the end of 2024, Wall Street’s verdict on Tesla versus BYD can be summarized as: Tesla is a growth-and-vision machine; BYD is a production-and-profit machine. Tesla’s market capitalization (and media excitement) reflects dreams of the future – autonomous fleets, energy grids, Martian colonies – that extend far beyond any spreadsheet. BYD’s value, while rising impressively, is still anchored in the conventional auto business.

Put another way, perception drives valuation. Tesla trades on its brand of innovation. BYD trades on its bottom line. Consider the price-to-earnings ratio: at times in 2025 Tesla has commanded a P/E in the hundreds (price $395 with earnings per share about $1.70, implying ~230x). BYD’s P/E is closer to 10–20x. These are not minor differences. An investor willing to pay $100 for $1 of Tesla earnings (because of “next decade” dreams) might only pay $15 for $1 of BYD earnings (viewed as a stable manufacturer).

Nor is this gap new. For much of the 2010s and early 2020s, Tesla’s valuation soared on promises of revolution, even during years when production was tiny. In 2020-2021 Tesla’s stock multiplier routinely exceeded those of Apple or Microsoft, despite Tesla selling far fewer vehicles than those tech giants sold phones or software. BYD, despite its age and sales volume, only recently began trading off its fundamentals more in Western markets. Many investors who missed the Tesla rally of the 2010s still believe it has farther to run, whereas BYD’s stock is just starting to wake them up.

Looking Ahead: Will the Gap Close?

Will Wall Street ever give BYD Tesla-like credit? It’s possible, but only gradually. If BYD’s global expansion accelerates – say, by opening more overseas factories or breaking into new markets – investors might start to view it as a multinational automaker rather than a regional champion. Already, its shares have been rising on news of “super-fast” chargers and new models, suggesting some analysts are taking notice. And if Chinese equities become more freely tradable (for example, via new Hong Kong-Shenzhen connect policies), BYD could attract more foreign capital and see its price multiple expand.

Conversely, if Tesla stumbles – if its growth slows drastically, or if technical challenges keep it from realizing promised leaps like robotaxis – some of its premium could vanish. In theory, as Tesla’s story falters and BYD’s fundamentals keep improving, the market might narrow the disparity.

That said, “betting on Musk” is not just a cliché. Investors do literally stake money on Musk’s narrative. One measure: Tesla was on track to briefly cross a $1 trillion market cap in mid-2024 after record production, reflecting market faith in its trajectory. As of late 2025 it hovers in the trillions, while BYD is still in the low hundreds of billions. In other words, the street’s expectation is that the future value of a Tesla share – propelled by Musk’s vision – will greatly exceed that of BYD regardless of current earnings.

This is a reminder that stock prices often reflect collective hopes more than cold calculus. Musk himself has played this game: he famously announced ambitious future products (like the October 2024 robo-taxi rollout) which helped keep Tesla in the headlines, even if deadlines slip. Wall Street, at least for now, seems to reward those headlines.

Valuation vs. Reality: What the Tesla–BYD Gap Really Means

The tale of Tesla vs. BYD is a classic clash between Silicon Valley fantasy and manufacturing reality. BYD’s 2024 results – sky-high revenues, surging sales and new factories – demonstrate that China has a world-leading EV powerhouse. But markets have their own priorities. Tesla’s market cap remains orders of magnitude larger, driven by investor psychology and Musk’s star power. Government policies in the U.S. (IRA credits, tariffs) and prevailing narratives about technology amplify Tesla’s lead.

For U.S. and global investors focused on growth and vision, Tesla is still the white knight of electrification. For analysts focused on balance sheets, BYD looks like the better value. In the end, Wall Street chooses to “bet on Musk over the numbers” because Musk’s narrative promises more than just car sales: it promises a new future. BYD’s equally impressive progress will continue to chip away at fundamentals, but it will take time (and perhaps a few more quarterly beats on Wall Street) for BYD’s valuations to reflect its full story.

Whichever way this story unfolds, one lesson is clear: in today’s market, perception can outweigh profit. Tesla and BYD may soon produce comparable profits and vehicles, but Wall Street’s enthusiasm is still ignited more by the spectacle of Musk than the spreadsheets of BYD.