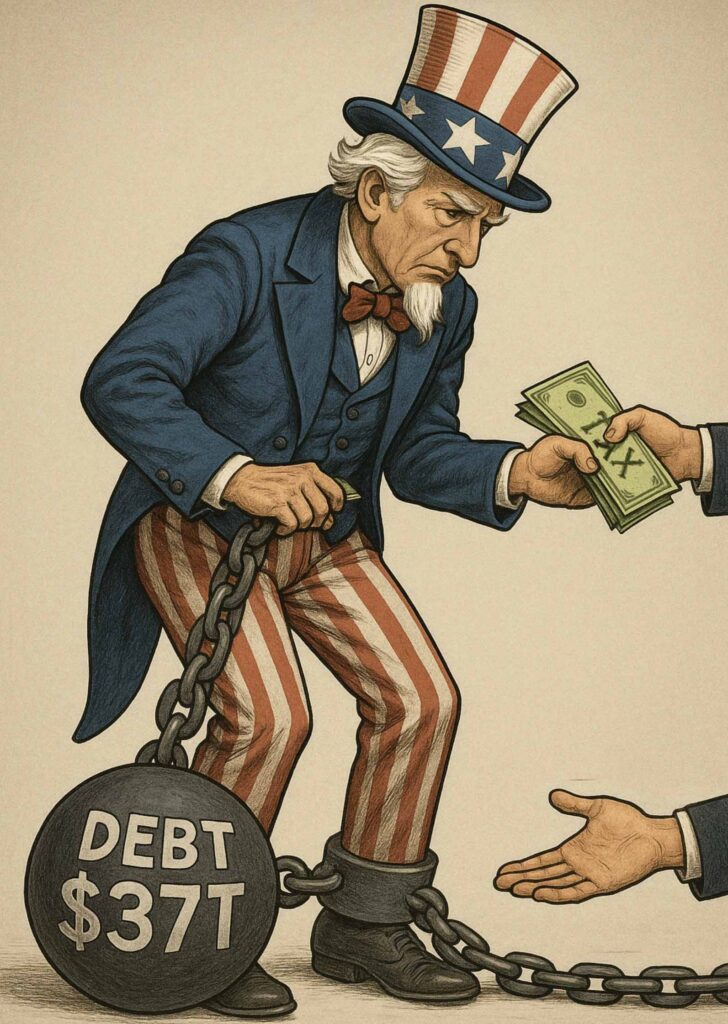

Trillions in debt, soaring interest costs, and your tax dollars on the line – the U.S. national debt has reached an unprecedented ~$37 trillion in 2025. This colossal figure is more than the entire U.S. economy produces in a year, and it works out to roughly $110,000 for every person in the country. While the government’s borrowing may seem abstract or remote, the reality is that interest payments on this debt are consuming a growing share of federal taxes. In fact, interest costs have surged to around $1 trillion per year – nearly one-fifth of federal revenues – meaning a significant portion of every tax dollar you pay goes not to schools, roads, or defense, but to service past borrowing. This article will demystify how America accumulated such a vast debt, who holds it, what drives it upward, and why the interest on that debt directly affects your taxes, public services, and the economy. We’ll explore key fiscal policy choices (from entitlement programs to military budgets and tax cuts), short- and long-term consequences of heavy debt, and the debates over whether this trajectory is sustainable. By decoding the national debt and its interest burden in plain language, we aim to shed light on how government borrowing ultimately shapes the nation’s financial future – and your own.

Origins and Growth of the U.S. National Debt

America’s debt story stretches back to the very founding of the republic. The U.S. has carried debt for as long as it’s been a country, beginning with loans to finance the Revolutionary War. For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the national debt rose during wars (such as the Civil War and World War I) and fell during peacetime growth. A dramatic turning point came in the 1940s: World War II required massive borrowing that pushed U.S. debt to about 120% of GDP (meaning the debt was larger than the yearly economic output). After the war, robust economic growth and disciplined budgets gradually shrank the debt relative to the economy. By 1970, debt was only around 35% of GDP. However, this trend did not last.

Beginning in the 1980s, the debt entered a new era of rapid growth. The Reagan administration implemented large tax cuts and a military buildup, and federal spending outpaced revenues. Annual deficits (the yearly gap between spending and tax income) ballooned, causing debt to climb. In the 1980s and early 1990s, debt as a share of GDP roughly doubled (from about 30% in 1980 to 60%+ by the early 1990s). A brief respite came in the late 1990s: a booming economy, spending restraints, and some tax increases produced budget surpluses from 1998–2001. During those few years, the government actually paid down some debt. But that progress was short-lived.

In the 2000s, several factors caused the debt to swell again. Early in the decade, the U.S. enacted major tax cuts in 2001 and 2003, reducing federal revenue. At the same time, spending increased with the launch of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq after 9/11. Those wars would ultimately cost trillions of dollars, much of it financed by borrowing. The combination of tax cuts and war spending turned surpluses into deficits. Then, in 2008, the Great Recession hit – the worst economic downturn since the 1930s. The government responded with bailouts for the financial system and stimulus spending to shore up the economy, while falling incomes meant lower tax receipts. As is typical in recessions, deficits widened sharply. By 2010, debt had grown to ~$9 trillion held by the public (roughly 60–65% of GDP). The debt kept rising in the 2010s albeit at a slower pace once the economy recovered, reaching around $16 trillion (80% of GDP) by 2019.

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 triggered another explosion of federal borrowing. Facing a sudden economic shutdown, Congress approved roughly $5 trillion in emergency relief for households, businesses, and hospitals. These rescue packages – though deemed necessary to prevent economic collapse – were financed entirely by borrowing. The economy also contracted briefly, which made the debt-to-GDP ratio spike. By mid-2020, debt soared to about 130% of GDP, an all-time record for the United States. Even after the immediate crisis passed, deficits remained very large in 2021 and 2022 due to ongoing stimulus, infrastructure spending, and rising costs of programs, while revenues did not keep up. As a result, the debt continued climbing rapidly. By 2025, the gross national debt (which includes both debt held by investors and debt the government owes to itself) reached $37 trillion, roughly 119% of GDP. In other words, the debt is now about 1.2 times the size of the entire U.S. economy – a level not seen since the aftermath of World War II.

Figure: U.S. gross national debt as a percentage of GDP, 2000–2025. The debt-to-GDP ratio climbed in three major waves – during the 1980s, after the 2008 financial crisis, and dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic – reaching roughly 120% in 2025.

It’s important to note that the dollar amount of debt will almost always hit new highs (because the economy and budgets grow over time), but the debt-to-GDP ratio puts it in perspective relative to the nation’s capacity to pay. Today’s debt ratio indicates that the U.S. is carrying significantly more debt relative to the economy than at almost any time in history. For decades after WWII, the U.S. managed to keep debt growth moderate, but in recent years spending has outpaced revenue by a wide margin. In fact, the government has run annual deficits every year since 2002, meaning it has borrowed money each year for over two decades straight. Even in good economic times, tax intake hasn’t covered all the spending, so the debt keeps accumulating. This persistent imbalance – basically the nation living beyond its means – is the core reason the debt is so large today.

Who Holds the $37 Trillion Debt?

When we talk about the U.S. “national debt,” who exactly is the money owed to? It turns out the debt is held by a variety of creditors, including foreign investors, U.S. citizens, financial institutions, and even parts of the government itself. Understanding who holds U.S. debt helps illuminate where those hefty interest payments are going – and what it means for Americans.

Broadly, the $37 trillion debt falls into two categories: debt held by the public and intragovernmental debt. Debt held by the public (~$30 trillion) refers to U.S. government bonds and other securities owned by outside investors – this includes individuals, banks, pension funds, mutual funds, foreign governments, and the Federal Reserve. Intragovernmental debt (~$7 trillion) is money the government owes to itself, chiefly to federal trust funds like Social Security and Medicare. For example, when the Social Security Trust Fund runs a surplus, by law it invests that surplus in special Treasury bonds – effectively lending money to the rest of the government. Such internal debt isn’t borrowed from the public, but it still counts in the total owed (because the government will have to pay those obligations back to the programs in the future).

Let’s break down the major holders of U.S. public debt (the $30T held by investors):

Figure: Who owns the U.S. public debt (approximate share by holder as of 2025). About two-thirds of the debt is held by private investors (domestic and foreign), with the remainder held by government accounts (trust funds) and the Federal Reserve.

- Private Investors (Domestic and Foreign) – Roughly two-thirds of the national debt is held by private investors around the world. This category (about $24–25 trillion) includes foreign investors, U.S. individuals, banks, insurance companies, mutual funds, corporations, and pension funds. In fact, about one-quarter of the U.S. debt is held by foreign parties. As of 2025, Japan is the single largest foreign creditor, owning around $1.1 trillion of U.S. Treasuries. China holds roughly $750 billion (down from past years), and other major holders include the United Kingdom and various countries in Europe, as well as international investors seeking a safe place to park money. The other roughly three-quarters of “private” holders are Americans – from large financial institutions to ordinary people who own Treasury bonds directly or via their retirement funds. U.S. mutual funds hold nearly $4½ trillion, and U.S. banks about $1½–2 trillion, with the rest spread across pensions, insurance companies, and individuals. In short, a substantial portion of the debt is effectively money Americans owe to Americans, while a significant share (around 23%) is money owed to foreign lenders. When interest is paid on the debt, it flows into the pockets of these bondholders. That means a portion of U.S. interest payments goes overseas (a transfer of income from U.S. taxpayers to foreign investors), and a portion goes to domestic investors (including retirees, banks, etc., for whom Treasuries are an investment asset).

- Federal Reserve – About 12–13% of the public debt (around $4½ trillion) is held by the U.S. Federal Reserve System. The Fed accumulated much of this during programs like “quantitative easing,” where it bought Treasuries to inject money into the economy (especially during crises like 2008 and 2020). While the Fed is part of the government, its holdings are counted in debt held by the public because the Fed is technically independent and buys bonds on the open market. The Fed rebating interest: The interest on bonds held by the Fed is mostly returned to the U.S. Treasury each year (after the Fed’s operating expenses), effectively reducing the net cost. In recent years, the Fed’s bond purchases helped keep interest rates low. However, as the Fed now lets some bonds mature or sells them (to tighten money supply and combat inflation), its holdings have slightly declined. The Fed’s role essentially means some portion of government debt is owed to itself, and interest paid ends up back in Treasury’s coffers – but only after going through the Fed’s books.

- U.S. Government Trust Funds and Agencies – The remaining portion, roughly 20% of the total national debt (~$7 trillion), is intragovernmental. Key holders here are programs like Social Security’s trust funds (~$2.7 trillion), Medicare trust funds (~$400 billion), and federal employee and military retirement funds (several trillion combined). These trust funds invested their surpluses in special Treasury securities over the years. For example, Social Security built up a large reserve from payroll taxes which peaked in recent years and is now being drawn down as the population ages. The government must pay back the trust funds with interest when they need the money to pay benefits. In essence, this chunk of the debt represents the government’s future obligations to its own citizens (for pensions and benefits). It’s debt in an accounting sense, though not owed to outside creditors.

What does this ownership structure mean for taxpayers? For one, interest payments on the debt get distributed to these holders. Payments to domestic bondholders remain in the U.S. economy (often benefiting seniors, investors, and institutions). Payments to foreign holders, however, are a net transfer out of the U.S. economy – dollars flowing abroad to service American debt. As of 2025, foreigners earn tens of billions in U.S. interest each year. The ownership mix also has implications for financial stability: a diverse base of creditors is generally good, but reliance on foreign investors means U.S. finances depend in part on global confidence. If major foreign lenders reduced their holdings, the U.S. might have to offer higher interest rates to attract other buyers. Fortunately, U.S. debt is still considered one of the safest assets in the world, and demand remains high.

It’s also notable that American households indirectly hold a lot of the debt via pension funds, 401(k) plans, mutual funds, and other investments. U.S. Treasuries are popular because they are seen as very low-risk. This means that when we pay taxes that go to interest, some of that interest might be cycling back into our own retirement accounts or insurance funds. However, in net terms, every dollar spent on interest is a dollar not spent on something else in the budget, which is why the rising share of debt owned by anyone – be it foreign or domestic – is a growing concern.

What Drives the Growing National Debt?

Why did the U.S. debt skyrocket to $37 trillion? The simple answer: yearly deficits – the government spending more each year than it collects in taxes – have piled up over time. But behind those deficits are specific policy decisions, economic events, and demographic trends. Let’s break down the major factors that have driven the debt’s growth:

- Major Wars and Defense Spending: Large-scale military engagements and defense buildups have been significant debt drivers. For instance, in the 2000s and 2010s, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (launched after the 9/11 attacks) were largely financed by borrowing. Estimates put the total costs of these conflicts (including long-term veterans’ care) in the range of $4–6 trillion. These costs didn’t hit all at once, but they added substantially to deficits over many years. Even beyond specific wars, the U.S. maintains a very large defense budget (around $800 billion annually in recent years). During the Cold War and subsequent “War on Terror,” defense outlays rose without equivalent tax increases, contributing to debt. In short, fighting wars or sustaining a global military presence has often meant heavy borrowing.

- Recessions and Economic Crises: Downturns are double trouble for the national debt – the government’s income falls (because people earn and spend less, so tax revenues drop) at the same time that spending rises (for things like unemployment benefits, food assistance, and stimulus efforts). The Great Recession of 2008–2009 is a prime example. The recession itself shrank revenues, and Washington enacted emergency measures like the 2008 bank bailout and the 2009 economic stimulus package to revive the economy. These actions added hundreds of billions to the debt. Similarly, the brief but severe COVID-19 recession in 2020 led to trillions in federal aid to households and businesses while tax receipts temporarily dipped. Historically, periods of crisis (the 1930s Great Depression, early 1980s recession, etc.) have seen debt surge as the government tries to spend its way out of trouble and cushion the public.

- Tax Cuts and Reduced Revenue: A less obvious but very powerful contributor to debt has been a series of tax cuts over the past few decades. Cutting taxes without commensurate spending cuts leads to higher deficits (since the government forgoes revenue but keeps spending). There were major tax reductions in 2001 and 2003 under President George W. Bush, another temporary cut in 2010 under President Obama (as part of stimulus), and a significant overhaul in 2017 (Tax Cuts and Jobs Act) under President Trump. The 2017 law, for example, slashed corporate tax rates by 40% and trimmed individual income tax rates; while supporters argued it might spur growth, it undeniably reduced the tax inflow. Analysts estimate that tax cuts since 2000 have added over $10 trillion to the debt by lowering revenue. Essentially, the U.S. has been collecting less money relative to the size of its economy than it did in earlier decades, even as it continues to spend on programs new and old. This structural gap has greatly widened deficits. Put simply, persistent low tax rates (relative to spending) have been a key driver of federal borrowing.

- Rising Entitlement Costs (Aging Population): Another major factor is the growing cost of entitlement programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. These programs are designed to support the elderly, disabled, and low-income households – and they are mandatory spending, meaning they run on autopilot based on eligibility. As America’s population ages (the Baby Boom generation reaching retirement), more people draw benefits and healthcare costs per person have risen. Thirty years ago, around 13% of Americans were 65 or older; today it’s about 17% and rising. More retirees mean Social Security outlays have ballooned (it’s now the single largest federal expenditure), and Medicare (healthcare for seniors) costs have surged as medical prices grow. These programs are largely funded by dedicated taxes (like payroll taxes), but those revenues haven’t kept pace with benefits promised. Consequently, the government has often had to borrow to make up shortfalls. The demographic wave will continue, putting pressure on future budgets. In essence, the U.S. is accumulating debt to honor its promises of retirement and medical benefits, because current taxes aren’t fully covering them. Without changes, these structural deficits in entitlements will keep adding to the debt each year.

- Other Spending Decisions: Beyond the big-ticket items above, numerous policy choices have added to debt. Creating or expanding programs (from education to farm subsidies to infrastructure projects) often involves upfront costs that are debt-financed if not offset. For example, the 2021 bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act authorized $1.2 trillion for improving roads, bridges, and more – a necessary investment to many, but one that increases borrowing in the near term. Even routine increases in discretionary spending (the annually budgeted funds for agencies, defense, research, etc.) contribute if not matched by revenue. Over time, even relatively small deficits compound. It’s worth noting that interest on existing debt has itself become a significant cost (we’ll delve more into this next): when debt grows, the interest payments on it also grow, sucking up more of the budget and necessitating further borrowing if not paid with taxes. This can become a vicious cycle.

- Low Interest Rates Enabled Higher Debt (Until They Rose): One subtle driver of the debt surge in the 2010s was the historically low interest rate environment. For much of the past two decades (especially after 2008), interest rates were very low – the Federal Reserve kept rates near zero and global investors eagerly bought U.S. debt at cheap rates. This meant the government could borrow heavily without feeling much immediate pain from interest costs. Politically, this reduced urgency to balance budgets. Trillions were added to the debt while interest expense stayed manageable. However, this dynamic reversed starting in 2022, when inflation picked up and interest rates jumped (more on that soon). The end of ultra-low rates suddenly made the existing debt load far more expensive to service.

In summary, the national debt swelled due to a combination of policy decisions (tax cuts, spending increases) and unexpected crises (wars, recessions, a pandemic). Each year that spending exceeded revenue, the debt grew larger. By 2025, annual deficits are running around $2 trillion, even in a time of low unemployment – a sign that the debt is now driven by structural factors, not just one-time emergencies. Simply put, the U.S. government has been consistently living beyond its means, borrowing to fund current spending rather than fully paying with current taxes. This habit has accumulated into the $37 trillion we owe today.

How Interest Payments on the Debt Work

Borrowing money isn’t free – whether it’s a household with a mortgage or the government with its trillions in debt, interest must be paid to those who lent the money. U.S. government debt takes the form of Treasury securities (bills, notes, bonds, etc.), which are basically IOUs promising repayment with interest. Understanding how interest on the national debt works is key to seeing why rising debt costs put pressure on taxes and budgets.

When the U.S. Treasury borrows (by issuing a bond), it agrees to pay the bondholder a certain interest rate. Some debt is very short-term (Treasury bills that mature in weeks or months) with interest paid implicitly at maturity, and some is long-term (Treasury bonds that can mature 10 or 20+ years from now) with interest (coupons) paid every six months. Interest rates on these securities are determined by a combination of factors: the Federal Reserve’s policies (which influence overall interest rates in the economy), market demand for Treasuries, inflation expectations, and the creditworthiness of the U.S. The simpler way to view it: when inflation is low and the Fed sets low benchmark rates, the government can borrow cheaply. When inflation rises or investors see more risk, rates go up and borrowing costs climb.

For a good part of the last decade, interest rates were extremely low. In fact, as recently as January 2022, the average interest rate on all U.S. federal debt was only about 1.5% – an extraordinarily low figure by historical standards. That was because a lot of the debt had been issued during the 2010s when rates were near zero. However, starting in 2022, the Federal Reserve began aggressively raising interest rates to combat high inflation. This had a direct effect on new government borrowing: each time Treasury refinances maturing debt or issues new bonds to cover deficits, it must do so at the current rates, which have more than doubled. By mid-2025, the average interest rate on U.S. debt had climbed to roughly 3.3%, the highest in well over a decade. That might still seem modest compared to the double-digit interest rates of the 1980s, but when you apply 3–4% interest to tens of trillions of dollars of debt, the annual interest cost explodes.

To illustrate: in 2015, net interest on the debt was about $250 billion for the year. In 2022, interest costs hit a then-record of about $475 billion – nearly double the amount just a few years prior. By 2024, annual interest had jumped to roughly $880 billion, and in 2025 it’s projected around $1 trillion. Think about that: over $1 trillion just in interest payments in a single year – that’s money spent without buying any new services or goods, simply servicing past borrowing. This surge is because both the debt grew larger and the rates on that debt went higher. If interest rates remain elevated or the debt continues to expand (or both), interest payments will keep climbing further.

It’s also important to understand that interest on the debt is an obligatory expense. The U.S. must pay its bondholders on time, every time, or else face default (which would be an economic catastrophe). In the federal budget, interest is classified as a “mandatory” expense, meaning it is automatically paid under existing law, much like Social Security benefits are automatically paid. Congress doesn’t annually vote on whether to pay interest – it’s baked in. If the government doesn’t have enough revenue to cover all its spending (which it usually doesn’t, hence the deficit), it must borrow even more to pay the interest. This can create a compounding issue: borrowing to pay interest adds to the debt, which then accrues more interest. (Fortunately, the U.S. has not yet fallen into a true debt spiral where it borrows just to pay interest indefinitely, but the risk grows as interest consumes a larger share of the budget.)

Another aspect is the maturity structure of the debt. U.S. Treasury debt comes due at various times – some every month, some years or decades away. The average maturity of U.S. debt is around 5–6 years. This means that each year, a significant portion of debt is being refinanced (old bonds mature and new ones are issued). In any given year, roughly one-fifth of the debt or more might roll over. During periods of rising rates, older bonds that were issued at low interest are replaced with new bonds at higher interest, quickly raising the overall interest burden. We’re seeing that effect now: a 3-month Treasury bill in 2020 had near-zero interest; in 2023–2024, a new 3-month bill might carry 5% interest. Multiply that by trillions of refinancing, and you see why the government’s interest bill has spiked.

To put it in everyday terms, imagine the government’s debt as a gigantic adjustable-rate mortgage that has enjoyed low teaser rates for years and is now resetting to a higher rate – the “monthly payment” has shot up. Except in this case, the payment is measured in hundreds of billions of dollars and funded by taxpayers.

The key point is that interest payments are the price of past borrowing, and as that price rises, it soaks up more of the government’s financial resources. It’s money that must be paid out to lenders regularly, similar to how a household must pay credit card interest or else face penalties. There’s no wiggle room: short of reneging on debt (which would destroy U.S. creditworthiness), interest is essentially the first claim on government funds. In recent months, we’ve even seen credit rating agencies express concern – Moody’s and Fitch have downgraded the U.S. credit outlook in part because of rising interest costs relative to revenue, signaling that if this trend continues, it could threaten the country’s sterling reputation for credit.

One additional nuance: you might hear the term “net interest” in budget discussions. Net interest is the interest outlays minus certain interest income the government receives (for example, on loans it has made, or from assets). It’s essentially the bottom-line interest cost to taxpayers. In 2024, net interest was close to $950 billion. Gross interest (before offsets) was just over $1 trillion. Either way, it’s enormous. And projections by the Congressional Budget Office show net interest continuing to be the fastest-growing major category of expenditure in coming years if policies don’t change.

In short, interest payments on the debt work like a relentless meter that keeps running. With a $37 trillion balance, even a moderately low interest rate generates an eye-watering annual charge. As rates or debt levels increase, the meter runs faster. This is why, as we’ll explore next, those interest payments have a very real impact on the budget, taxes, and public services – because that money has to come from somewhere.

How Interest Payments Shape Taxes and Public Spending

When you pay federal taxes – whether income tax, payroll tax, or others – you probably expect that money to fund government services and programs that benefit the public. And indeed it does: your tax dollars go toward things like national defense, education, healthcare programs, infrastructure, and so on. However, an ever-larger slice of the tax pie is being eaten up before it can reach those public services. That slice is interest on the debt. In effect, a portion of your taxes is diverted to pay creditors who lent money to the government in the past. Let’s unpack how these interest payments are shaping taxes and spending:

- Portion of Taxes Going to Interest: As of 2025, roughly 15–20% of all federal tax revenue is used just to pay interest on the debt. To put that in perspective, imagine you pay $10,000 in federal taxes this year – about $2,000 of that might be going straight to interest payments, not to any program that directly serves you. Another way to look at it: interest outlays equal around 40% of the amount collected in personal income taxes. So, if you filed your taxes and saw how much was withheld or paid, almost half of that, in aggregate, is matched by interest expenses. This doesn’t mean each person’s specific taxes only go to interest, but overall it illustrates the burden. The share of taxes absorbed by interest has been climbing and is projected to keep rising. Essentially, past borrowing (debt) is imposing a “tax within the tax” – siphoning off today’s taxpayer money to pay for yesterday’s expenses.

- Crowding Out Public Services: Every dollar the government spends on interest is a dollar not available for other priorities unless the government borrows more or raises more revenue. In the federal budget, interest is now so large that it competes with and even exceeds what is spent on many programs. For example, in the 2024 fiscal year, the U.S. spent about $880 billion on interest. Compare that to other expenditures: that was more than the annual budget for Medicare (around $874 billion) and more than the entire defense budget (around $870+ billion). In 2025, interest payments are on track to be the second-largest item in the federal budget, behind only Social Security. This is a dramatic change – just a few years ago, interest was well below defense or healthcare spending. As interest costs grow, they threaten to crowd out spending on things like education, infrastructure, research, and social programs. Lawmakers face tough choices: Do they cut back on these services to free up money for interest? Do they allow deficits to grow even more to fund both interest and programs? Or do they raise taxes to cover the gap? None of these choices is politically easy, which is why rising interest often squeezes out less politically protected areas of the budget (for instance, it might be easier to trim an education grant or transportation project than to default on interest or suddenly slash Medicare benefits). Over time, if interest keeps gobbling a larger share, the government could find it harder to finance new initiatives or maintain existing ones. The term “crowding out” is often used: interest payments crowd out other government investments. This could mean fewer infrastructure improvements, less funding for national parks, or constrained military capabilities – all because a chunk of money is locked in to pay bondholders.

- Impacts on Public Services Today: Already, we can see subtle effects. For instance, if interest costs hadn’t risen so sharply, some of that money could have been used to shore up programs that are underfunded. Consider an area like education or scientific research – relatively small parts of the budget that often see funding pressures. The federal government’s interest bill increase from 2019 to 2025 (an increase of several hundred billion dollars annually) is equivalent to multiple times the Department of Education’s budget. One could argue that high interest spending is like having a huge credit-card bill limiting what else you can buy. America finds itself paying for past spending (via interest) rather than future-oriented investments. For citizens, this can translate to things like fewer services, aging infrastructure unrepaired, or simply a larger national debt (if the government chooses to borrow even more to also fund services). No matter what, taxpayers bear the cost – either through their taxes directly servicing debt or through the opportunity cost of services foregone.

- Pressure for Higher Taxes: As interest costs soar, there is an underlying pressure on the government’s finances. If policymakers want to maintain services and benefits without letting deficits explode, they may eventually have to consider raising taxes to cover the interest. In fact, some budget analysts point out that to stabilize debt, revenues as a share of GDP would need to rise. This could mean future generations might face higher tax burdens largely just to pay the interest on debts accumulated by prior spending. Conversely, if there is resistance to raising taxes (as is often the case), interest costs then just get added to the deficit, which in turn increases the debt, creating a vicious cycle that ultimately may necessitate even more drastic measures later. From the taxpayer’s perspective, either route – higher taxes now or potential fiscal crisis later – can be traced back in part to the weight of interest payments.

- Economic Growth and Private Sector Crowding Out: The effect of government interest payments isn’t just felt in the public sector; it also has macroeconomic implications. When the government is devoting significant portions of the budget to interest, it often means the government is borrowing heavily from the financial markets to get that money (since our revenue doesn’t fully cover it). Heavy government borrowing can put upward pressure on interest rates in the economy (especially when the economy is near full capacity). This can lead to what economists call “crowding out” of private investment. Essentially, the government’s appetite for credit can drive up the cost of loans for businesses and consumers. If businesses face higher interest rates on loans or bonds because capital is scarcer or pricier, they may invest less in expansion, new equipment, or hiring. Over time, that means slower economic growth than might have occurred with lower government debt. Additionally, if more of the nation’s savings are going to buy government debt (a safe investment) rather than being invested in private ventures (like startups, factories, research), this can erode productivity growth. While U.S. Treasury bonds are vital to the financial system, every dollar that goes into Treasuries is a dollar not invested in, say, a new business. Thus, a high-debt, high-interest scenario could indirectly lead to a smaller or less dynamic economy over the long haul, which affects everyone’s prosperity.

- Interest Payments and Inequality: Another angle to consider is who ultimately receives interest payments. A significant share of U.S. debt is owned by wealthy individuals, financial institutions, and foreign investors. When taxpayers as a whole pay interest, that money flows to these bondholders. In a way, it can be seen as a transfer from the general taxpayer base to relatively wealthier creditors. (Of course, many middle-class people hold Treasuries too via retirement accounts, but the biggest holders tend to be wealthier entities and foreigners.) This dynamic isn’t often front and center in policy debates, but it’s worth noting: paying interest on debt can have distributional effects, moving money around in the economy in ways that don’t necessarily benefit the average citizen as much as direct government spending might. For example, if the government spends $100 million on building a highway, that employs workers and creates a public asset. If the government instead spends $100 million on interest, that might simply enrich bond investors with no broader public good created.

In summary, interest payments act as a significant claim on government resources before any new spending decisions can even be made. They shape taxes by absorbing a large chunk of what’s collected – effectively forcing taxpayers to finance past expenditures. They shape public spending by constraining what’s available for present and future needs, unless we borrow more (which only kicks the can down the road). And they can shape the economy by influencing interest rates and investment patterns. The more the United States must devote to servicing its debt, the less fiscal flexibility it has. That is why many economists and officials are worried: not only is the debt historically large, but the cost of carrying that debt is rising, directly impacting today’s budget and potentially tomorrow’s economic opportunities.

U.S. Fiscal Policy Choices: Entitlements, Defense, and Taxation

How did we end up with such a mismatch between spending and revenue? To a large extent, it boils down to policy choices – the big-ticket priorities the U.S. government has committed to, and how (or whether) it pays for them. The three areas that dominate fiscal policy debates are entitlement programs, defense spending, and taxation policy. Each has played a role in the debt story, and each is crucial to any solution.

1. Entitlement Programs (Social Security, Medicare, and more): These are programs that provide benefits to individuals – primarily seniors, the disabled, and the poor – and they are called “entitlements” because eligible people are entitled by law to receive the benefits. The largest ones are Social Security (which provides retirement and disability income) and Medicare (which provides health insurance for those over 65 and some younger disabled people). There’s also Medicaid (health coverage for low-income Americans) and a few others. These programs account for a huge portion of federal spending – for instance, Social Security alone is about 20% of the federal budget, and Medicare another ~15%. They are also growing every year due to demographic and cost trends. Social Security is paying benefits to the massive Baby Boomer generation now, and people are living longer. Medicare not only has more enrollees as the population ages, but healthcare costs per person tend to rise over time with new treatments and inflation in medical prices.

The challenge is that these programs are mandatory spending and politically sensitive. No politician wants to tell seniors or vulnerable populations they’ll get less. Yet, these programs are not on sound financial footing long-term. For example, Social Security has begun paying out more in benefits each year than it collects in payroll taxes; it’s drawing down its trust fund, which is projected to be exhausted in the 2030s, after which benefits would automatically have to be cut ~20% unless the program is shored up. Medicare’s hospital insurance trust fund also faces depletion in the next decade or so. The growth of entitlement spending has been a major driver of higher federal outlays. But Congress has been reluctant to make big changes (like raising the retirement age further, modifying benefit formulas, or raising payroll tax rates) due to the popularity of these programs.

As a result, to keep these entitlements fully funded, the government has often resorted to borrowing when dedicated revenues (like payroll taxes) fell short. In other words, rather than cut benefits or significantly raise taxes for Social Security and Medicare, the government borrowed the difference. This has added trillions to the debt over time. Any serious plan to rein in long-term debt likely has to address entitlements – either by reforming them to spend less or finding new revenue to support them, or a combination. It’s a tough political nut to crack: one side fears harming retirees and the social safety net; the other fears the unsustainable cost. The result so far has been mostly stalemate, with the debt quietly growing in the background.

2. Defense and Security Spending: The United States spends more on defense than any other country – by far. The annual Pentagon budget (plus related expenditures like Veterans’ Affairs and homeland security) regularly approaches or exceeds $800 billion. During active conflicts, supplemental spending bills often added more on top of the base defense budget. For instance, the post-9/11 wars were largely funded through emergency appropriations that were essentially put on the national credit card. Defense spending, like entitlements, is often considered untouchable by many politicians, due to concerns about national security and supporting the military. In fact, adjusting for inflation, the defense budget in recent years has been near historically high levels (comparable to peaks during Vietnam or the 1980s), though as a share of GDP it’s lower than mid-20th century due to the economy’s growth.

Defense outlays contribute significantly to the deficit when they aren’t offset by other cuts or taxes. For example, in the 1980s, President Reagan increased defense spending dramatically to challenge the Soviet Union, but taxes were simultaneously cut – the debt climbed as a result. More recently, even as wars have wound down, the defense budget hasn’t contracted drastically; new strategic competitions (with China and Russia) and modern military needs (cybersecurity, etc.) keep pressure on spending upward. Some argue that there is plenty of waste or overspending in defense that could be trimmed without harming security (for instance, costly weapons programs or maintaining more bases than necessary). Others argue the world is dangerous and the U.S. must invest heavily in its military, debt be darned.

From a debt perspective, sustained high defense spending means higher baseline deficits unless matched by higher taxes or cuts elsewhere. In the debt reduction debates, defense is often one category considered for tightening. Indeed, past budget deals (like in the 2010s) included caps that limited growth in defense (and non-defense) discretionary spending. But those caps expired and spending is rising again. The decision to fund a very strong military is a policy choice with a price tag – and for decades the U.S. has often chosen to not fully pay that price in the present (via taxes), instead deferring it to the future (via debt).

3. Taxation Policy: On the revenue side of the ledger, U.S. tax policy has profound implications for debt. The United States historically has a lower tax-to-GDP ratio than most other advanced economies. Federal revenues (taxes) have averaged around 17% of GDP over the past 50 years. Meanwhile, federal spending has averaged around 20% of GDP, and is higher in recent years. This gap is the structural deficit. Why not raise taxes to close it? This is where political philosophy enters: many U.S. policymakers (especially conservatives) prioritize low taxes to encourage economic growth and let people keep more of their money, whereas others (typically progressives) advocate higher taxes on corporations or the wealthy to fund programs and reduce inequality. The result has been periodic swings, but overall a reluctance to raise broad-based taxes significantly.

As mentioned earlier, the Bush-era tax cuts and the Trump tax cuts significantly reduced revenue from what it would have been. Even parts of the Obama administration’s stimulus included tax cuts (e.g., payroll tax holiday) to boost consumption. At the same time, there hasn’t been a major new federal tax (like a value-added tax or carbon tax) that many other countries introduced to raise money. The federal tax system leans heavily on income and payroll taxes, with corporate taxes and other sources being smaller shares. Over time, lobbyists and lawmakers also carved out many deductions, credits, and loopholes which narrow the tax base.

One can argue that political decisions to underfund the government’s spending level through tax policy have fueled the debt. For example, had the U.S. maintained revenue at 20% of GDP (rather than ~17%), the deficits would be much smaller or nonexistent in some years. Another example: since 2001, the country fought wars and expanded Medicare (with a prescription drug benefit in 2003) without raising taxes to pay for them – a departure from earlier norms (in WWII or Vietnam, taxes were raised significantly to share the burden). In recent discourse, letting the 2017 tax cuts expire as scheduled in 2026 for individuals is a contentious issue – extending them would mean trillions more in foregone revenue over the next decade, but raising taxes (even back to pre-2017 levels) is politically tough.

It’s also worth noting that tax enforcement and compliance are part of the picture. The IRS estimates hundreds of billions in taxes go unpaid each year (the “tax gap”). Funding for the IRS to pursue tax cheats could theoretically yield more revenue and reduce deficits without raising rates, but that too became a political football.

In essence, fiscal policy in the U.S. for many years has been characterized by a bipartisan tendency to give the public low taxes and high spending – a politically pleasing combination in the short run, but one that inevitably leads to borrowing. Republicans often emphasize cutting taxes and have also increased defense spending; Democrats often emphasize expanding social programs and are cautious about cutting entitlements; compromise sometimes ends up being doing a bit of both and letting debt fill the gap.

A few key decisions from the past illustrate this dynamic:

- The early 2000s: Instead of safeguarding the late-90s surpluses for future Social Security strain, leaders chose to cut taxes and engage in costly wars, pivoting back to deficits.

- The 2010s: Following the Great Recession, there was a temporary focus on deficit reduction around 2011 (leading to spending caps and some tax increases on the wealthy in 2013), but soon after, both parties agreed to bust those caps and increase spending. In 2017, despite an already large debt, a major tax cut was passed, arguing it would boost growth. It did coincide with some growth and low unemployment, but deficit spending also increased during a prosperous period (normally when you’d want to reduce debt).

- COVID-19 response: Virtually all policymakers agreed on massive borrowing to address the emergency, prioritizing immediate relief over debt concerns (understandably). But even after the emergency, new initiatives (infrastructure, stimulus checks, etc.) continued, partly debt-funded.

Entitlements, defense, and taxes are the three pillars that any solution to the debt problem must grapple with. For example, reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio could require measures like: slowing the growth of Social Security/Medicare (perhaps by a combination of benefit trims and healthcare cost reforms), restraining or carefully prioritizing defense spending, and finding additional revenue (maybe higher taxes on high earners, or consumption taxes that the U.S. currently doesn’t use). None of these are pain-free options, which is why debt tends to be an issue often acknowledged but rarely aggressively acted upon.

It’s important to note that fiscal policy is about trade-offs and priorities. There is nothing inherently “wrong” about deciding to run a deficit to fund a war or a social program if that is judged to be worth the cost. But over the long term, the accumulation of those choices is reflected in the debt – and the bill for that shows up in the interest line of the budget. The current $37 trillion debt is a ledger of past decisions: tax cuts enjoyed, wars fought, social benefits paid, emergencies addressed – all without fully offsetting payments at the time. Recognizing this helps inform the debate about what to do going forward: should the U.S. scale back some commitments, ask citizens to contribute more in taxes, or some of both, to align our fiscal path with reality?

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Consequences

Is the towering national debt an imminent crisis, or more of a long-term drag? The answer is debated, but it’s useful to distinguish between the short-term effects of high debt and interest payments and the long-term consequences if current trends continue.

Short-Term (Today and the Next Few Years): In the immediate term, the U.S. has been able to manage its debt load without an acute crisis. Interest rates, while higher now, are still at levels the economy can tolerate. The Treasury is successfully issuing new bonds, and there remains strong global demand for U.S. debt (owing to the dollar’s reserve currency status and U.S. Treasuries being seen as a safe asset). The government has not had trouble rolling over debt or raising funds for its day-to-day operations – apart from self-inflicted political dramas like debt ceiling standoffs, which we’ll mention shortly. Unemployment is relatively low, and the economy, despite high debt, has grown in recent years. In fact, running deficits in certain situations (like during the COVID recession) provided a short-term economic boost and likely staved off deeper pain.

In the short run, high government debt doesn’t necessarily cause obvious harm in the way a personal debt problem might (where bill collectors show up). A sovereign government that issues its own currency can keep things afloat as long as investors believe in its creditworthiness. For now, the U.S. benefits from that belief. Also, interest payments, while large, are being met. There’s no immediate inability to pay them – they’re being covered by a combination of taxes and additional borrowing. Inflation, which spiked in 2021–2022 partly due to pandemic supply issues and stimulus, has begun to moderate, suggesting that the situation isn’t spiraling out of control at this moment.

However, short-term does not mean no concerns at all. One pressing near-term issue is the debt ceiling battles. The U.S. has a statutory limit on debt (the debt ceiling) that Congress must raise periodically. In recent years, debates over raising this limit have become contentious, with some lawmakers using it as leverage to demand spending cuts or other policy changes. In 2011 and again in 2023, brinkmanship over the debt ceiling came dangerously close to causing a government default on its obligations. Even the whiff of potential default can rattle markets and has led to credit rating downgrades (Standard & Poor’s downgraded the U.S. in 2011, and Fitch did in 2023). While these are political crises rather than economic necessity, they are short-term risks directly tied to the debt: with debt so high, the ceiling gets hit more frequently, and political polarization turns it into a recurring flashpoint. If an actual default happened even for a few days, it could cause chaos in financial markets and increase long-term borrowing costs due to a loss of trust.

Another short-term effect already visible is that as the government devotes more to interest, it has less flexibility to respond to new challenges. For instance, if a recession hit next year, normally policymakers might want to inject stimulus. But with annual interest costs already around $1 trillion, there might be hesitation or constraints on massive new borrowing (especially as the Federal Reserve is now tightening rather than easing). This doesn’t mean the government can’t respond at all – it certainly can and likely would – but the fiscal space is more limited than when debt was lower. Think of it like a family that already has a lot of credit card debt and then faces a job loss; they can still borrow more to get through it, but there’s a risk of maxing out and they have to be more careful.

In the very short term, the impact of high debt on everyday people is subtle. You won’t necessarily notice it week by week – except perhaps that interest rates on mortgages and loans are higher than they’d be if government debt (and resulting Fed rate hikes) were lower. If you’re a saver or investor, you might benefit from higher interest yields on bonds due to government borrowing. If you’re a borrower, you might face slightly higher costs. The big obvious changes – like slashing of government programs or significant tax hikes – have not happened yet. So for many Americans, the short-term status quo with high debt feels pretty normal, which can breed complacency.

Long-Term (The Next Decades): It’s when we peer further out that the picture grows more worrisome. If current policies persist – meaning large yearly deficits continue, debt keeps rising faster than the economy, and interest costs mount – the U.S. could eventually face a debt crisis or at least severe financial strain. There are a few potential long-term scenarios:

- Soaring Interest Costs Bite Hard: Projections by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and others show that if we don’t change course, interest payments will climb to record levels as a share of the budget and economy. We’re talking interest potentially reaching $1.5 trillion or more per year within a decade, and consuming, say, 20–25% of all federal revenues. At that point, the government either has to greatly increase revenue, cut spending drastically, or keep borrowing in a way that could spook investors. Under a status quo scenario, by the 2030s or 2040s, the debt could double relative to GDP. Carrying that debt could become unsustainable if investors demand higher interest to compensate for risk, creating a spiral. The government might be forced to make painful adjustments: sudden steep tax hikes, abrupt spending cuts, or monetization of debt (basically printing money via the Fed buying more debt), which could trigger high inflation.

- Risk of Fiscal Crisis: While it’s impossible to predict a precise tipping point, many economists warn that continuous debt accumulation could lead to a crisis of confidence. This could manifest as a spike in bond yields (interest rates) if investors fear they won’t be repaid in full or worry about inflation eroding the value of bonds. For a country like the U.S., a classic default is unlikely as long as it borrows in its own currency – but a default is not absolutely impossible if political dysfunction (e.g., failing to raise the debt ceiling) occurs. More likely, a “crisis” would be inflationary: if markets think the U.S. will try to inflate away its debt or that the Fed will have to keep rates low despite inflation to help the Treasury, they might lose faith in the dollar’s value, causing a currency and inflation problem. Hyperinflation is an extreme scenario and not expected for the U.S. barring truly reckless policy, but even a moderate bout of high inflation can be very painful (reducing purchasing power, prompting recessions when fought with high rates, etc.). Another angle: if debt continues to climb, at some point foreign investors (or even domestic ones) might reduce lending, forcing the U.S. to offer higher interest or risk a funding crunch.

- Economic Drag and Generational Burden: Even without an acute crisis, a high debt path can slowly erode a nation’s prosperity. Resources spent on interest are not spent on infrastructure, education, or research – which are the foundations of future growth. Over time, that can mean a less productive economy. Additionally, if heavy borrowing crowds out private investment, it means fewer businesses formed or expansions made, leading to lower productivity and wage growth. Future generations could find that a lot of their tax dollars go just to servicing debt incurred before they were born, limiting the government’s ability to invest in their future or requiring them to pay much higher taxes for the same services. We often talk about “passing the burden” to future generations: this is usually what it means – tomorrow’s workers having to pay for yesterday’s spending, with potentially less to show for it. It can also create intergenerational tension: young people may resent high taxes to pay benefits for a large retired population, while older people feel they’re owed the benefits promised. The debt is in part a reflection of that social contract straining.

- Hard Choices and Reforms Forced by Circumstance: In a long-term view, one way or another, the gap between spending and revenue must close. If done proactively, it could be gradual and sensible (a mix of policy adjustments). If postponed until markets demand it, it could be sudden and severe. For instance, if one day interest rates jump and the U.S. finds itself unable to easily borrow, it might have to enact austerity measures abruptly – slashing budgets and raising taxes in a short span. We’ve seen countries like Greece go through that (though the U.S. is not Greece – it controls its currency and has a far larger economy – but the general principle of losing fiscal freedom applies at some limit). Such a scenario would likely lead to a sharp recession and political turmoil. It’s far better to avoid reaching that point. The long-term consequence of continuing on our path is that the U.S. edges closer to a point where external or internal pressures force a reckoning.

- National Security and Global Standing: A more intangible long-run effect is on the country’s global power. If debt and interest constrain economic growth and squeeze out defense or diplomacy budgets, the U.S. might have less ability to project power or invest in cutting-edge technology, etc. Also, being the world’s largest debtor potentially gives leverage to some foreign creditors (though in reality, they can’t easily pull out without hurting themselves, as the U.S. economy is deeply interlinked globally). Nonetheless, some worry that if the debt weakens the economy, it could, in time, weaken America’s leadership position in the world.

It’s not all doom and gloom – there are also scenarios where things could stabilize. For example, if the U.S. implements moderate reforms (slightly higher taxes, some spending restraint) and the economy grows steadily, the debt-to-GDP ratio could be tamed. Or a burst of productivity (say from a tech revolution) could boost GDP faster, making the debt more manageable relative to the economy. Additionally, inflation, while harmful in many ways, does erode the real value of existing debt if wages and GDP rise with it; indeed, post-WWII, a mix of inflation and growth helped the U.S. reduce its debt ratio significantly. However, counting on inflation is risky – uncontrolled inflation brings other problems.

In essence, short-term, the debt is like a slow burn; long-term, it could become a wildfire if left unattended. We’re already seeing early sparks – rapid interest cost growth, political frictions – that hint at future difficulties. The prudent approach, many economists say, is to take action while things are stable (i.e., now) to avoid the worst-case outcomes later. That means planning for the aging population costs, gradually adjusting taxes and spending, and setting debt on a sustainable path before it’s done in crisis mode.

In summary, short-term: no immediate catastrophe, but growing strains; long-term: an unsustainable course that, if uncorrected, will constrain America’s future and could lead to crisis. Recognizing the difference is important – it’s why some argue we should act now even though things feel okay, to ensure they remain okay later.

International Comparisons and Perspectives

The United States is far from the only country with a large national debt. Many other nations, especially after the global financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic, have seen their debt levels rise significantly. Comparing the U.S. situation to others can provide context on what’s “normal,” what’s risky, and how interest payments shape budgets elsewhere.

Debt-to-GDP Around the World: By global standards, the U.S. debt (around 120% of GDP) is high, but not the absolute highest. Japan holds the title for the highest debt-to-GDP ratio among major economies – over 230% of GDP. Japan’s situation, however, is unique: the vast majority of its debt is held by its own citizens and institutions, and for decades Japan had ultra-low or even negative interest rates. That meant Japan could carry a huge debt without high interest costs; in fact, interest consumes only around 8% of Japan’s budget (as of a couple years ago) – much lower than the U.S. percentage – because their government pays very low rates on its bonds. However, even Japan is starting to feel pressure: as its central bank hints at raising rates slightly, interest expenses are projected to shoot up by 50% in a few years. Japan’s debt is a cautionary tale of how debt can accumulate in an aging society, but also an example that if you can keep interest low (and have domestic savers), you can avoid crisis – at least for a long time.

European Countries: In Europe, debt levels vary. Countries like Greece (which had debt around 180% of GDP in recent years) and Italy (about 150% of GDP) have struggled with high debt. Greece famously had a debt crisis in 2010–2012, requiring international bailouts and painful austerity, because investors lost confidence in its ability to repay – partly since Greece doesn’t control its own currency (it’s in the Eurozone) and couldn’t devalue or print money. Italy, also in the Eurozone, managed to avoid Greece’s fate largely because the European Central Bank intervened to buy Italian bonds and calm markets, but its debt remains a vulnerability. Germany, on the other hand, has kept its debt relatively modest (around 60–70% of GDP), partly due to cultural aversion to debt and constitutional “debt brake” rules. France and Spain are around 110–120% and 100% of GDP respectively, not far off from the U.S., after taking on a lot of debt during the pandemic.

The European Union sets a theoretical limit of 60% of GDP for member countries’ debt (and 3% of GDP for deficits) in its rules, but many countries exceed those, and enforcement is lax especially after the pandemic. What Europe shows is that high debt isn’t solely a U.S. phenomenon, but responses differ. Some European countries raised taxes or cut spending significantly in the 2010s (the era of “austerity”) to try to rein debt in – with mixed results and often social unrest. The U.K., outside the EU, has debt about 100% of GDP. A recent episode there in 2022 illustrated market discipline: a new government proposed big unfunded tax cuts that would’ve increased borrowing, and markets reacted swiftly with higher interest rates for U.K. bonds, forcing a reversal of the plan. This signaled that markets can indeed push back on fiscal policy if they sense irresponsibility – even for a developed nation. The U.S. hasn’t faced that kind of market rebellion, but it’s a reminder it’s not impossible.

Emerging Markets: Many developing countries traditionally had lower debt ratios but often pay higher interest due to risk. Some have defaulted at debt levels (relative to GDP) that are much lower than what the U.S. has, primarily because they borrow in foreign currencies or don’t have the same credibility. For example, a country like Argentina has defaulted multiple times; its debt might have been, say, 60% of GDP, but if it’s in dollars and investors flee, that’s enough to cause collapse. The U.S. has the advantage that its debt is in dollars, and the Federal Reserve can always print dollars in a crunch – which is why a U.S. “default” would likely be an inflationary money-printing one, not an inability to pay.

Reserve Currency Privilege: The U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency (used in trade, held by central banks worldwide) gives the U.S. a special edge. It creates a natural demand for dollars and dollar-denominated assets (like Treasuries). Many other countries don’t have that: if they print too much money or borrow too heavily, their currency plunges and inflation soars. The U.S., to some extent, can spread its debt around the world and people still want more – at least as long as faith in the U.S. remains. This “exorbitant privilege,” as it’s sometimes called, has allowed America to run larger deficits without immediate crisis than any other country could. But it’s not a license to be reckless forever. If the U.S. were ever to undermine confidence in its currency or bonds (through hyperinflation or chronic political dysfunction), that privilege could erode, and the adjustment would be painful (suddenly we’d have to live within our means much more strictly).

Interest Burdens: When comparing interest burdens internationally, one measure is interest as a percentage of GDP or as a percentage of government revenue. The U.S. is now around 3% of GDP going to interest and roughly 15-18% of revenue. Those numbers are rising. By comparison, Japan’s interest is about 1-1.5% of GDP (very low, again thanks to near-zero rates). Italy’s interest is about 3-4% of GDP (similar to the U.S. now), and since Italy’s revenue is higher relative to GDP (Europe taxes more), interest is maybe around 8-10% of Italy’s revenue. Some emerging economies have to spend a big chunk of their revenue on interest – for instance, a country like Egypt or Pakistan sometimes spends over a third of revenue on interest, which crowds out needed spending (and often leads them to seek IMF help). The U.S. isn’t near those extremes yet, but it’s moving in the wrong direction.

Handling Debt: Different nations have tried different strategies to handle high debt:

- Economic Growth: This is the ideal: grow out of the debt. After WWII, the U.S. and U.K. had huge debts but then had strong growth (and some inflation), so the debt-to-GDP ratio plummeted even without paying debt off – they just outgrew it. Many policymakers hope for growth to outpace debt increases again. But with an aging population and moderate growth rates, it’s unclear if growth alone can do the trick now.

- Austerity: Some countries have cut spending or raised taxes sharply to reduce deficits (e.g., Britain in the 2010s, some Eurozone crisis countries). This can lower debt but often at the cost of short-term economic pain and public pushback. The U.S. has generally avoided severe austerity – which some see as good (to not harm the economy), but it also means we haven’t made much debt progress.

- Structural Reforms: Some nations implement changes to reduce future liabilities – e.g., raising retirement ages, reforming pensions, or healthcare systems – to slow debt growth. The U.S. has been very slow on this front in recent years, whereas some countries like Sweden or Canada reformed pensions decades ago when facing demographic shifts.

- Default or Restructuring: This is what happens when countries truly can’t pay (like Greece partially did, or Argentina repeatedly) – they negotiate to pay creditors less than owed or delay payments. For a global financial lynchpin like the U.S., defaulting would be catastrophic globally, so it’s really not considered an option. The U.S. can always technically pay in dollars – the issue is will those dollars be worth anything if overprinted.

Lessons and Warnings: One global lesson is that high debt becomes risky when lenders doubt a country’s political will or economic ability to manage it. The U.S., despite its high debt, still enjoys relatively low borrowing costs because investors trust the U.S. economy and its institutions. If that trust erodes, the U.S. could face a reckoning that other countries have faced, but on a scale the world has never seen. That’s why maintaining credibility (e.g., avoiding debt-ceiling fiascos, addressing long-term challenges) is important. Another lesson: countries with aging populations (Japan, much of Europe, U.S. to a slightly lesser extent) all face rising debt from pension and healthcare obligations. This is a global challenge – how to care for an older population without drowning in debt. Some countries, like Germany, instituted higher retirement ages and strong export-driven growth to cope; others, like Italy, struggled due to lower growth and political constraints.

It’s also worth noting differences in taxation: Many peer countries fund their larger social programs with higher taxes (for instance, a European value-added tax, VAT, which is like a national sales tax, often 20% on goods). The U.S. lacks a VAT and relies more on income taxes. If the U.S. were to align its revenue more with those peers, it could raise a lot more money (though that comes with its own economic impacts).

In conclusion, international comparisons show that the U.S. is not alone in having high debt, but the U.S. stands out in absolute size and global impact. We have advantages (global currency, strong institutions) that have allowed more leeway. But other countries’ experiences should serve as both inspiration (for example, Canada in the 1990s successfully tamed large deficits through bipartisan effort, and its debt-to-GDP dropped significantly) and caution (the turmoil seen in places that waited until a crisis to act). Ultimately, no economic law exempts a country from fiscal gravity forever – not even the United States. But by learning from global examples, the U.S. can hopefully make the choices that avoid the worst outcomes and maintain economic leadership.

Debates on Debt Sustainability, Tax Burdens, and Reform Options

The national debt and how to handle it is a subject of lively debate among economists, policymakers, and the public. There are competing viewpoints on how much debt is too much, whether we should worry now or later, and the best ways to address it (or whether to address it at all). Let’s outline a few key perspectives and proposed solutions:

1. The Debt Sustainability Debate:

- Fiscally Conservative View (Debt Hawks): Many budget watchdogs, economists, and conservative policymakers argue that the current debt path is unsustainable and dangerous. They often liken the government to a household or business that can’t indefinitely spend beyond its means. They point to the rapidly rising interest costs and high debt-to-GDP ratio as red flags that, if ignored, could lead to an eventual crisis. This camp often emphasizes immediate action to reduce deficits – “the sooner, the better” – to avoid saddling future generations with impossible burdens or risking a tipping point where investors lose faith. They also worry that high debt will force either punishing tax increases or severe inflation down the road. For these thinkers, the national debt is a top-priority problem that intersects with national security (as high debt could limit defense resources or make the U.S. beholden to creditors like China) and moral responsibility (not leaving our children to pay our bills). They frequently call for spending cuts (especially on entitlements which drive future debt) and pro-growth policies to help shrink the debt relative to the economy. Organizations like the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget or the Concord Coalition, for example, advocate for comprehensive deficit reduction plans. In political terms, many Republicans (at least rhetorically) align with this view, focusing on spending restraint, though their follow-through varies. Some centrists and Democrats also share concern about long-term debt (witness the Simpson-Bowles commission in 2010, a bipartisan group that proposed a mix of cuts and taxes to stabilize debt).

- Moderate/Keynesian View: Some economists and policymakers take a middle ground – acknowledging that high debt is a concern, especially long-term, but also cautioning against overreacting in the short term in ways that could harm the economy or vulnerable populations. They tend to argue that while debt levels are high, the current cost of debt is manageable (especially if interest rates remain below the economy’s growth rate) and that precipitous austerity (like sudden big spending cuts or tax hikes) could do more harm than good, particularly if the economy is weak. They advocate a gradual, balanced approach: for instance, pairing modest spending curbs with targeted tax increases, and implementing reforms that take effect over time (like slowly raising retirement age over decades, or a multi-year plan to raise revenue) so that the economy and people have time to adjust. This view also emphasizes that not all debt is equal – borrowing to invest in things that boost future growth (infrastructure, education, R&D) is better than borrowing for wasteful or purely consumptive spending. So, some debt can “pay for itself” indirectly if it expands the economy’s capacity. Many Democratic policymakers and centrist economists fall into this pragmatic category: they don’t dismiss debt concerns but prioritize other short-run issues (like maintaining employment and funding important programs) while suggesting we tackle debt in a sensible, phased manner. They often support things like closing tax loopholes, slightly higher taxes on the wealthy, and entitlement tweaks that protect the most vulnerable while improving solvency.

- Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and Dovish View: A more radical departure comes from proponents of Modern Monetary Theory and some progressive economists. MMT argues that a country like the U.S., which issues its own sovereign currency, cannot “run out of money” the way a household can, and therefore should not focus on nominal debt levels. The key claim is that the government can always create more money to pay its bills, and the constraint on spending is not solvency but inflation. In this view, as long as there are unused economic resources (unemployment, for example) and inflation is low, the government can and even should run deficits to boost the economy or achieve social goals. MMT advocates note that the U.S. has been able to borrow at low rates and that dire predictions about debt (like those made in the 1980s or 1990s) often didn’t come true. They often ask: if the economy clearly needs investment (say in infrastructure or climate change mitigation), why arbitrarily hold back due to debt fears, especially when borrowing costs are low? However, MMT does acknowledge that if inflation becomes a problem, the government should then raise taxes or cut spending to cool the economy (thus controlling inflation rather than worrying about debt per se). MMT is controversial and has many critics who argue it downplays the risks of excessive money creation and inflation (indeed, some say the big COVID fiscal stimulus was influenced by such thinking and contributed to the inflation uptick in 2021-22). But its influence has been to encourage more tolerance for deficit spending, particularly on the left. Even among economists who don’t fully buy MMT, some will argue that as long as interest rates are below the growth rate of GDP, debt can gradually melt away or be managed (a concept known as the debt-to-GDP stabilizing condition). They point out that advanced countries like the U.S., with credible institutions, can carry more debt without crisis than previously thought. This is a more dovish stance on debt – not saying “debt doesn’t matter at all,” but saying “we have time and bigger problems to solve first.”

2. Tax Burden and Fairness Debates:

Another major debate is who should bear the burden of fixing the debt, via taxes or spending cuts? If taxes are to be raised, should it be the wealthy, corporations, the middle class, consumption taxes that everyone pays?

- Those favoring higher taxes on the wealthy and corporations argue that in recent decades, top income earners and big companies have seen taxes fall (e.g., top income tax rates are well below what they were in the mid-20th century, and corporate taxes as a share of GDP have dropped). They suggest that restoring some of those taxes could raise significant revenue without harming middle or lower-income Americans. For instance, letting the 2017 tax cuts expire for top brackets, taxing capital gains at the same rate as wages, closing loopholes, or even wealth taxes on billionaires have been proposed. If such measures were enacted, the additional revenue could be used to pay down deficits (or at least prevent them from growing). The idea here is to address the debt without putting more burden on those who are already struggling. Many progressives favor this route, often coupling it with the idea that the rich benefited from deficit-fueled growth (like asset bubbles from low interest rates) so they should contribute more to fixing it.

- Those favoring broader taxes or spending cuts counter that simply soaking the rich won’t be enough. They point out that even dramatically higher taxes on the wealthy might not close the gap entirely, and that there’s risk of discouraging investment or driving wealth abroad. Some suggest more universal taxes, like a small national sales tax or value-added tax (which most other countries have) to raise revenue from the large consumer base – this would hit everyone, but potentially modestly if done right, and could fund things like healthcare or debt reduction. Others note that middle-class Americans might eventually have to pay somewhat higher taxes too if we truly want European-style social benefits without debt – because in Europe, middle classes do pay more in VAT and social contributions. This is not politically popular, so it’s often avoided in rhetoric.

- Spending cut advocates argue the problem is not that taxes are too low but that spending is too high. They often target entitlements and other mandatory programs, as that’s where the growth is. For example, suggestions include raising the Social Security retirement age (people live longer, so work longer), slowing benefit growth for higher-income retirees, converting Medicare to a voucher-like system or raising its eligibility age, block-granting Medicaid to control costs, and tightening eligibility for things like disability benefits. On discretionary spending, they might suggest cuts to certain departments, or reducing federal roles to save money (for example, spending less on departments that states could handle). Defense is sometimes exempt in their talking points (especially for conservatives), but others suggest even defense can be made more efficient. The challenge is that specific cuts often face backlash – seniors oppose Social Security changes, defense hawks oppose military cuts, etc. Nonetheless, spending hawks say without trimming the biggest drivers (entitlements), any fix is incomplete.

3. Inflation Concerns:

There’s also debate about how the debt intersects with inflation. One viewpoint (especially in conservative circles) is that excessive government debt can lead to the government effectively pressuring the Federal Reserve to monetize it (i.e., print money to buy bonds), which could cause inflation. They sometimes cite historical examples of countries that printed money to get out of debt and ended up with hyperinflation (e.g., Zimbabwe, or more relevantly, how 1970s high inflation in the U.S. was partly attributed to the Fed being too accommodative of government deficits). While the U.S. isn’t at hyperinflation risk, the high inflation in 2021-22 has renewed these arguments: was it partly because we borrowed and spent trillions in stimulus? Many say yes – too much stimulus (fiscal and monetary combined) overheated demand, causing inflation. This serves as a caution that running big deficits in a strong economy can be inflationary – basically too many dollars chasing too few goods.

On the other side, some argue the recent inflation was more due to supply chain issues and pandemic disruptions, and that prior to the pandemic, debt had doubled in a decade with no sign of inflation – in fact, inflation was quite low in the 2010s. So they say debt per se isn’t inevitably inflationary; it depends on context (like slack in the economy). But even those would concede that if you try to finance endless deficits by printing money, you will eventually get inflation. Thus, the debate is where that line is. With the Fed now raising rates to tackle inflation, it shows a willingness to prioritize price stability – even though that ironically raises interest costs on debt further. So there’s interplay: the more debt, the more painful it can be to raise rates to fight inflation (since taxpayers pay the interest). Some worry this could tempt future Fed leaders to allow a bit more inflation (to ease debt burden) instead of fighting it aggressively – essentially an implicit default on debt via inflation. Preserving the Fed’s independence and anti-inflation credibility is crucial to avoid that scenario.

4. Future Policy Reforms:

Given all these perspectives, what are some concrete reform options floated to address the situation? Here are a mix of ideas that often come up, reflecting different philosophies: