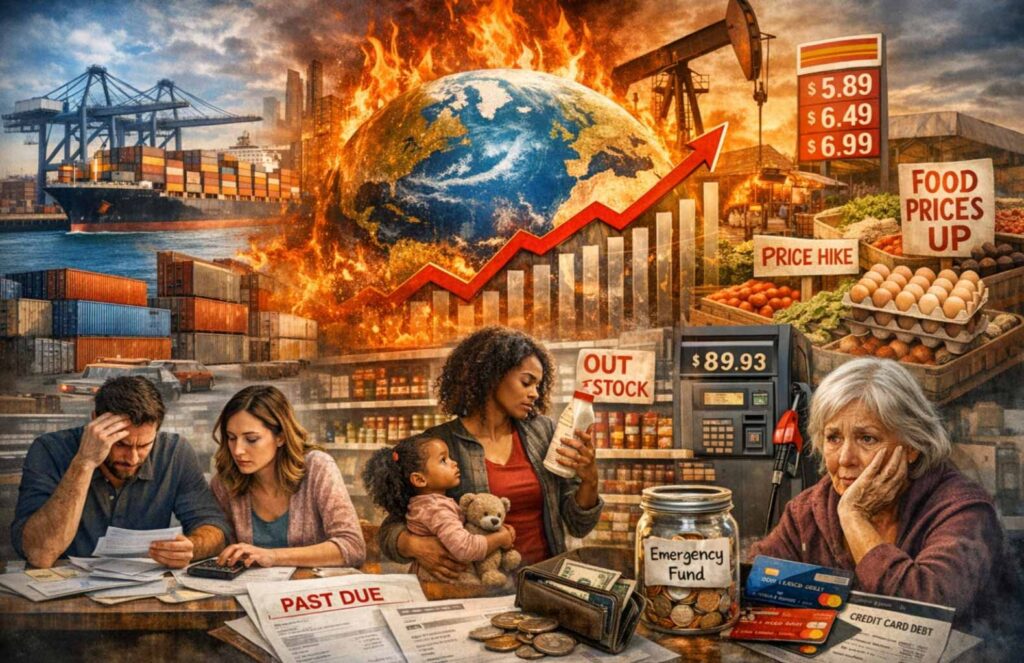

Inflation is back with a vengeance across the globe, and everyday people are feeling the pain. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, consumer prices have surged at rates not seen in decades, catching many households and policymakers off guard. Shoppers from Chicago to Cairo have watched the cost of food, fuel, housing, and other essentials climb relentlessly. Yet even as paychecks grew in nominal terms, wages have failed to keep pace with the soaring prices. This disconnect – prices racing ahead while pay stagnates – has eroded real purchasing power for millions. In 2022, global inflation hit its highest level since the mid-1990s, with many countries experiencing their steepest price increases in a generation. But that same year marked the first decline in real worldwide earnings of the 21st century, as global average wages fell by 0.9% after adjusting for inflation. In the United States, consumer prices jumped over 9% in the 12 months through June 2022 – a 40-year record – while wages grew only around 5%, effectively shrinking workers’ buying power. Across advanced economies, inflation has outstripped pay, meaning most workers got a real pay cut even if their paycheck was nominally larger. The result is a cost-of-living crisis: families are paying more for basics even though their incomes aren’t rising enough to cover the difference. This article blends a journalistic narrative with academic insight to explore why inflation has spiked globally, why wage growth hasn’t kept up, and how this imbalance is impacting different communities. We will examine the forces driving prices higher – from supply chain kinks to energy shocks, monetary policy, corporate pricing power, and more – and why the burden of inflation falls unevenly across society. We’ll also compare today’s inflationary surge with episodes from the past, and discuss why policy responses often fail to fully ease the public’s suffering. The goal is to shed light on the dynamics behind “global inflation, local suffering,” and to explain in clear terms why prices soar even when wages don’t.

The Inflation Surge: Global Spike Meets Stagnant Pay

After years of relative price stability, inflation made a dramatic comeback worldwide starting in 2021. As pandemic disruptions eased and economies reopened, pent-up consumer demand collided with constrained supply, igniting price hikes across sectors. By mid-2022, the inflation rate in the United States hit 9.1% – the highest since 1981. The eurozone likewise saw record inflation (over 8%), the highest since the euro was created. Many other countries from the United Kingdom to Brazil, Turkey, and beyond experienced their fastest price growth in decades. This was truly a global phenomenon: the median worldwide inflation rate jumped from under 2% in 2020 to about 8% by 2022. In other words, after a dormant period, inflation suddenly roared back to life nearly everywhere.

Yet even as consumer prices soared, wages did not remotely keep up in most cases. In the United States, average hourly earnings were rising at a roughly 4–5% annual pace in 2021–2022, far below the inflation rate that peaked above 9%. The biggest gap came in June 2022, when wages were up 4.8% from a year earlier but inflation was 9.1%, leaving workers 4.3% poorer in real terms on average. U.S. workers’ inflation-adjusted weekly earnings fell over the course of 2022 despite a tight labor market, illustrating how paychecks lagged behind price increases. This pattern was echoed globally. An International Labour Organization report found that global real monthly wages fell by 0.9% in 2022, marking the first such drop in the 21st century. In high-income countries, the decline was even sharper: real pay fell by an average 3.2% in North America and 2.4% in the European Union, as inflation in those regions outpaced nominal wage growth. In effect, inflation gave workers an across-the-board pay cut. While households saw bigger numbers on their pay stubs, those dollars or euros bought fewer groceries, gallons of gas, or kilowatts of electricity than before. It’s a one-two punch: prices rising at the fastest clip in forty years, and wages not rising fast enough to maintain living standards.

Why haven’t wages kept up? Part of the answer is timing – inflation surged very quickly, and wages tend to adjust more slowly and unevenly. Another factor is that many workers have weak bargaining power in today’s labor markets, especially after decades of globalization and declining unionization (issues we’ll explore later). There was also an initial belief among policymakers that inflation would be “transitory,” which led some employers to hesitate in raising pay aggressively. The bottom line is that the cost of living has been climbing much faster than incomes. In the U.S., the median household income rose about 12% from 2019 to 2023, but the overall cost of living jumped roughly 20% in that time. That 8-point gap represents a significant erosion of purchasing power. As a report by NerdWallet noted, since 2019 the cost of essentials has risen nearly twice as much as median income. Families are essentially getting poorer in real terms, even if headline economic numbers (like low unemployment or nominal wage gains) seem positive. This disconnect between prices and pay is at the heart of the current public frustration. Polls consistently show that large majorities of people feel financially strained despite a strong job market, because their paychecks don’t stretch as far at the store. In sum, we are living through an unusual moment where inflation is sky-high but wage growth is not, and it’s causing widespread economic pain.

To understand how we got here, we need to examine the drivers behind the global inflation spike and why those forces didn’t translate into commensurate wage gains for most workers. A complex storm of factors converged: pandemic aftershocks in the supply chain, volatile energy and commodity prices, huge swings in monetary and fiscal policy, corporate pricing strategies, and structural trends like globalization. We will break down each of these in turn. Together, they help explain why a burst of inflation took off around the world – and why ordinary workers are bearing the brunt without seeing equivalent boosts in their pay.

Post-Pandemic Supply Chain Shockwaves

One of the first sparks that ignited inflation was the disruption of global supply chains during the pandemic. In early 2020, worldwide production and trade were upended: factories closed, workers stayed home, and shipping routes stalled. When consumer demand rebounded in 2021, the system struggled to catch up. The result was a classic supply-demand mismatch: too many dollars (or euros, etc.) chasing too few goods. Shortages and bottlenecks popped up in everything from microchips to furniture to shipping containers, driving prices skyward.

By 2021, stories of supply chain chaos were making headlines. Container ships backed up at major ports, waiting weeks to unload. A shortage of semiconductor chips hit auto production, sending new and used car prices soaring. Retailers faced delays restocking inventories, and “out of stock” notices became common for many products. This phenomenon showed up directly in inflation data: durable goods (like cars, appliances, electronics) saw especially steep price increases for the first time in years. In the U.S., goods inflation outpaced services inflation in 2021 – a reversal of the usual pattern – indicating how supply constraints for physical products were a key driver. Consumers flush with stimulus money wanted to buy items like home exercise equipment or new laptops, but global manufacturing and logistics simply couldn’t keep up at normal prices. Companies that did have inventory found they could charge more, given the high demand.

Economists estimate that these supply chain disruptions were a major contributor to the inflation spike. Research by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland concluded that both strong demand and supply factors (including supply-chain snarls) “contributed significantly” to the high inflation of 2021–2022. When analysts tried to parse how much of the unexpected inflation was due to supply issues, they often found supply shocks to be dominant. One empirical study found that global supply chain problems were the single largest driver of U.S. inflation in 2021–2022 – more than any other individual factor. Increases in a popular index of global supply chain pressure were strongly correlated with rising prices. In plain terms, broken supply chains meant scarcer goods, which meant higher prices.

A World Bank analysis similarly noted that after staying low for years, global inflation surged in 2020–2022 largely because of supply disruptions and a rapid rebound in demand. At one point in 2022, supply bottlenecks were estimated to be adding several percentage points to the U.S. inflation rate. Certain sectors provided vivid examples: the shortage of new cars (due to lack of chips) led to a bizarre jump in used car prices by over 40% year-on-year in 2021, heavily boosting the consumer price index. Shipping costs for international freight routes quintupled or more, and those costs passed through to consumer prices for imported goods. Manufacturers facing higher input costs (whether for parts or transportation) adjusted by charging more downstream. Thus, the tangled global supply web – normally invisible to consumers – suddenly became a prime mover of inflation.

Importantly, these supply strains took time to resolve. By mid-2022, there were signs that port backlogs and delivery times were improving, which helped ease goods inflation somewhat. Indeed, inflation in durable goods began cooling by late 2022 as supply chains healed and retailers worked off excess inventories. However, the damage was done: the initial supply shocks had set off a broad inflationary wave. They also had distributional consequences. Products that are more essential or have fewer substitutes (like certain auto parts or medical supplies) experienced sharper inflation, which hurt consumers who rely on them. And because supply-driven inflation doesn’t come with higher wages (unlike a classic wage-price spiral), it immediately translates to a real income loss for workers. In short, post-pandemic supply chain breakdowns “primed the pump” for inflation, creating scarcity and higher costs in key goods markets, which then cascaded into the prices paid by households. This was one critical reason prices shot up even as paychecks didn’t – workers had little control over these global logistical problems, yet they felt the impact in the form of pricier cars, appliances, and other goods.

Energy Price Volatility and Commodity Shocks

If strained supply lines set the stage for inflation, soaring energy and commodity prices poured fuel on the fire. Energy is a foundational input for virtually everything – when the cost of oil, gas, and electricity jumps, it ripples through the entire economy. And that’s exactly what happened in 2021–2022. After collapsing early in the pandemic, global oil prices rebounded sharply, then spiked further with geopolitical turmoil. By mid-2022, crude oil was trading around $120 a barrel, roughly double its price a year earlier, driven in large part by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent supply disruptions. Gasoline and diesel prices shot up in tandem. In the United States, gasoline hit a record national average of over $5 per gallon in June 2022, contributing to a 41.6% year-over-year increase in overall energy prices – the largest jump since 1980. Within that, fuel oil was up an astonishing 70% over the year, and gasoline itself nearly 60%. Households felt the pain directly at the pump and in utility bills, and indirectly in the higher cost to produce and transport all manner of goods.

The war in Ukraine in early 2022 was a pivotal trigger for energy volatility. Russia is one of the world’s top oil and natural gas exporters, and the conflict (along with sanctions on Russia) constrained global supply. Natural gas prices particularly skyrocketed in Europe, which had relied heavily on Russian gas – leading to eye-watering increases in heating and electricity costs across Europe in late 2021 and 2022. Globally, the Russian invasion sent oil, gas, fertilizer, and grain prices soaring. This constituted a classic commodity shock, reminiscent of the 1970s oil embargo that led to stagflation. Suddenly, many essential commodities were more scarce and expensive on world markets. Energy companies saw profits surge to record levels amid the high prices, while consumers saw their expenses climb.

Higher energy costs feed into inflation in multiple ways. There is the direct impact – for instance, the energy component of U.S. consumer inflation was up over 40% in mid-2022 as noted. But energy also raises production and transportation costs for businesses, who often pass those costs on. A farmer faces pricier fuel for tractors and higher fertilizer costs (since fertilizer is made from natural gas), which can translate into more expensive groceries. A trucking company paying more for diesel will charge retailers more to ship goods, which can lead to higher shelf prices. Airfares jump when jet fuel prices climb. Even service industries feel it: utility bills for restaurants or schools go up, adding pressure to raise fees or cut elsewhere. In short, energy is a universal input, so an energy price shock has an amplifier effect on broad inflation.

In 2021–22, we saw that dynamic play out. Energy-driven inflation was especially brutal because it heavily affected necessities. For example, natural gas utility prices rose nearly 40% in the U.S. over the year to June 2022, straining household budgets for heating and cooking. Electricity prices were up nearly 14%, the most in over a decade. And as fuel and fertilizer costs increased, food prices followed suit – global food commodity indices hit all-time highs in spring 2022. Staples like wheat, vegetable oils, and meat became markedly more expensive worldwide. In the U.S., grocery prices rose over 12% year-on-year in mid-2022, the steepest climb since 1979. Many developing countries, where food is a larger share of consumer spending, experienced even worse. Low-income nations saw heightened risks of hunger and unrest due to spiking bread and oil prices. Thus, the energy and commodity shock not only fueled inflation in statistical terms, but it intensified the hardship on consumers, particularly the poor, who spend a greater fraction of their income on food and fuel.

Geopolitical conflict amplified this trend. Beyond Ukraine, other events – such as OPEC oil production decisions, sanctions, or extreme weather – added uncertainty to commodity markets. For instance, droughts in some regions cut crop yields, boosting grain prices. All these factors made commodity prices highly volatile and on an upward trend during the inflation surge. By early 2022, inflation in many places was being driven heavily by energy and food costs. Even as central banks began raising interest rates (which we’ll discuss next), those tools cannot directly bring down oil or wheat prices – that requires supply increases or demand reduction in those markets. This is why central bankers often emphasize “core” inflation (excluding food and energy), but from a household perspective, food and energy are exactly where the pinch was fiercest.

In summary, the spike in energy and commodity prices acted as an accelerant for global inflation, coming on top of the supply chain issues. It pushed up the price of critical goods and services around the world. And because these prices are set in global markets, even countries with stable domestic policies could import high inflation via higher fuel or food costs. For consumers, it meant huge hits to their real income: any wage gains were quickly eaten up by gasoline fill-ups and grocery bills. The energy shock underscores a cruel aspect of inflation – it often strikes hardest in areas people can’t avoid spending on, leaving little room to maneuver.

Monetary Policy: The Fed and the Flood of Money

Another key piece of the inflation puzzle lies in monetary policy and the actions of central banks, especially the U.S. Federal Reserve. In simple terms, a rapid expansion of the money supply and prolonged ultra-low interest rates helped set the stage for an overheating of demand. When the pandemic hit in 2020, central banks around the world unleashed unprecedented monetary stimulus to prevent an economic collapse. The Fed slashed its benchmark interest rate to near zero, began buying trillions of dollars in bonds, and effectively printed money at a historic pace to support lending and spending. These actions were successful in stabilizing financial markets and spurring a rapid recovery – but they also meant a lot more money was chasing goods and services, which can be a recipe for inflation, especially once the economy’s productive capacity is constrained.

To put numbers on it, the U.S. money supply (M2) ballooned by approximately 40% in less than two years due to the Fed’s interventions. From March 2020 to the end of 2021, the Fed’s asset purchases and lending programs injected about $6.4 trillion of new money into the economy – a 42% increase in M2 in just 22 months. This scale of expansion was far beyond normal, and far above what economic output growth could absorb. In essence, there was a tsunami of liquidity. Initially, much of this money piled up in bank reserves or was saved by households (some of it in stimulus checks). Inflation remained low in 2020 because demand was depressed by the pandemic. But by 2021, with vaccines and reopening, that extra money contributed to surging demand. People had cash in their accounts and were eager to spend, buy homes, cars, etc., aided by very cheap credit (mortgage rates hit record lows around 2-3%). The Fed’s intention was to spark recovery, but in hindsight many economists argue it overstimulated, given that supply was still constrained.

Milton Friedman’s old adage, “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” seemed relevant. While not the sole cause, easy money and low rates undoubtedly helped fuel the inflation by boosting spending power. The American Farm Bureau Federation noted that the Fed’s massive money creation in 2020 was “turning, inevitably, into inflation” once the economy reopened. By late 2021, inflation had leapt well above the Fed’s long-run 2% target, yet the central bank initially believed this was temporary “transitory” inflation that would abate on its own. This delayed a policy response. In retrospect, the Fed kept monetary conditions too loose for too long into 2021, even as warning signs of persistent inflation emerged (like rising housing rents and wages). When it became clear that inflation was not fading, the Fed pivoted abruptly. Starting in March 2022, the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates at the fastest pace in decades. In a span of about one year, U.S. short-term interest rates went from near 0% to over 5% – a speed of tightening roughly twice as fast as the last big cycle in the 1980s. Other major central banks (European Central Bank, Bank of England, etc.) also began aggressive rate hikes in 2022, all aiming to slam the brakes on inflation.

This monetary whiplash – first a flood of liquidity, then a sudden tightening – has had mixed effects on wages and prices. On one hand, the earlier easy money clearly boosted asset prices and demand, which contributed to inflation without equivalent wage gains for workers (since money flowed into many channels, including financial markets). On the other hand, the subsequent interest rate hikes are cooling off demand by design, which may slow inflation but often at the cost of slower wage growth and rising unemployment risk. Higher interest rates hit sectors like housing particularly hard: mortgage rates more than doubled, making home-buying unaffordable for many and eventually tempering home price inflation. But for those who don’t own homes, that’s cold comfort – rent inflation actually accelerated even as the Fed tightened, because higher mortgage costs kept more people in the rental market.

It’s worth noting that monetary policy can have distributional impacts. The initial low-rate environment benefited borrowers and those with assets (stock prices and home values surged), while savers earned almost nothing on deposits. The subsequent high-rate environment helps savers and cools asset markets, but it also raises debt service costs for households (credit card and loan interest rates have jumped). Crucially, raising interest rates – the main tool to fight inflation – does little to directly lower the price of groceries or gasoline in the short run. What it does is slow down overall economic activity, hopefully enough to curb demand and ease price pressures over time. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has acknowledged that the burdens of high inflation fall heaviest on those least able to afford it, and that the Fed is “intent on tackling inflation” even if the medicine (rate hikes) is painful. Indeed, central bankers face a dilemma: act too slowly and inflation may become entrenched; act too aggressively and they risk causing a recession, which also hurts workers.

Monetary policy’s role in the recent inflation can be summarized as follows: extraordinary stimulus helped economies rebound strongly from the pandemic, but likely overheated demand relative to supply, contributing to the price surge. Then, monetary authorities played catch-up, quickly tightening policy to restrain inflation, which is now helping cool price growth but also damping wage growth and broader economic momentum. In short, the era of “free money” ended in a rush, and we are seeing its aftereffects. For the average worker, this sequence meant that any gains from a hot economy (like plentiful jobs or slight wage upticks) were largely negated by the higher cost of living – and now they face a tougher job market as central banks tap the brakes.

Corporate Profits and Pricing Power: The “Greedflation” Debate

Amid the turmoil of supply shocks and stimulus, another controversial factor in the inflation story emerged: the role of corporations’ pricing strategies and profit margins. Some economists and commentators have pointed out that many companies were able to raise prices well beyond their own cost increases, fattening profit margins in the process. This has been colloquially dubbed “greedflation” – the idea that corporate opportunism or market power allowed prices to soar more than necessary. While not all experts agree on the magnitude of this effect, evidence shows that corporate profits contributed markedly to the initial inflation surge, especially in 2021.

During the early phase of the pandemic recovery, numerous companies enjoyed a rare combination of circumstances: booming demand for their products, coupled with supply shortages that limited competition and supply. This allowed firms to hike prices without losing customers. In technical terms, the price elasticity of demand was low – consumers were willing to pay more because goods were scarce (and many had extra savings from stimulus). The result was a jump in corporate profit margins. By late 2021, U.S. corporate profits (after tax) hit record highs both in absolute terms and as a share of GDP. Analysis by the Economic Policy Institute found that from the end of 2019 to mid-2022, rising profits accounted for over 40% of the increase in prices in the U.S. nonfinancial corporate sector, far above the typical 11–12% contribution of profits in normal times. In other words, a significant chunk of inflation was linked to higher unit profits, not higher costs. Even by mid-2023, profits still explained roughly one-third of the price increase since 2019, indicating that margins remained well above pre-pandemic norms.

Why did this happen? Economists like Josh Bivens of EPI argue that pandemic distortions granted many producers temporary pricing power “akin to monopoly power” in key sectors. Industries like shipping, semiconductors, commodities, and retail goods saw consolidation or bottlenecks that let the dominant suppliers or firms charge top dollar. Additionally, some companies likely took advantage of the general inflationary environment as cover to raise prices more than needed – a phenomenon sometimes called “excuseflation.” For example, if input costs went up 5%, a firm might raise its product price 10% and blame “inflation” or supply chain issues, thereby widening its margin. This is easier to do when the whole market is seeing price increases, so it doesn’t stick out as much to consumers.

The data bears out that profits surged at the same time inflation did. The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City noted that corporate profits were the main contributor to U.S. inflation in 2021. Specifically, in the first few quarters after the 2020 recession, profit growth accounted for a large portion of price increases – a pattern the researchers found was consistent with past recoveries. Historically, after a recession, you often see profits jump while costs (like labor) are still subdued; firms set prices anticipating future cost rises, an instance of “anticipatory price-setting”. This appears to have happened again: businesses raised prices early on, boosting profits, and only later did costs like wages start rising and eating into those margins. The Kansas City Fed study showed that by 2022, profits’ contribution to inflation started to fall as labor and other costs caught up. But the initial spike was significant. Chart analysis going back to the 1940s confirms that inflation driven by profits tends to spike right after recessions and then moderate – exactly what we saw in 2021–22.

This is not to say that “greed” alone caused inflation – clearly, underlying supply/demand factors were at play. However, corporate behavior influenced how those factors translated into final prices. How much firms mark up prices over costs (their markup or margin) can amplify inflation if they choose to expand margins. During 2021, it seems many did. One striking point from EPI is that normally in a booming economy, competition and rising costs keep profit shares in check or even shrinking (as wages go up). But the pandemic recovery was unusual: in a hot economy, profit shares actually rose to multi-decade highs, implying an imbalance. Bivens notes that historically, as the economy heats up, labor’s share of income rises and profit’s share falls – yet post-2020, the opposite initially happened. This suggests corporate power was leveraged in a different way: instead of suppressing wages (as in the past), firms maintained or raised prices aggressively, taking advantage of disruptions.

Some real-world examples illustrate this dynamic. Major American companies in sectors like consumer goods, food, and transportation reported robust earnings and in investor calls admitted to hiking prices in excess of cost increases. For instance, some food conglomerates faced maybe 15–20% higher input costs but raised product prices by 25–30%, pocketing the difference. Energy companies obviously benefited from high oil/gas prices, yielding record profits in 2022, but many did not rapidly increase production (which could lower prices) – they instead kept supply limited and enjoyed high margins. Shipping companies (container lines) in 2021–22 had unprecedented profit windfalls as freight rates went up tenfold on some routes.

To be sure, by 2023 as the economy normalized, some of these extreme profit margins began to revert down. Input costs like labor were rising (wages belatedly climbing, as we will discuss) and consumers started pushing back or seeking cheaper alternatives as inflation wore on. The Kansas City Fed observed that by the second year of recovery, costs displace profits as the main inflation driver. Nevertheless, the initial phase of inflation was disproportionately a profit story. European Central Bank research similarly found that in Europe, profits contributed more to inflation in 2021–22 than wage increases did – an atypical pattern. This has fueled debate: were companies price-gouging and exploiting crises, or just naturally taking what the market gave? Regardless of motive, the outcome was that a notable share of inflation ended up in corporate earnings, not workers’ pay. One could cynically say companies could raise prices because consumers had little choice, and they did – hence record margins.

For workers, this meant that even as their own wages might have started to inch up, those gains often went to pay for pricier goods where the extra money was flowing to corporate profits. In a sense, there was a transfer of purchasing power from consumers to producers. It also helps explain the political anger at “profiteering” during inflationary times. The narrative of “greedflation” gained enough traction that some governments considered windfall profit taxes or price controls on essential goods. While the full extent of profit-driven inflation is debated, it’s clear that pricing power was a part of the story of why prices ran ahead of wages. Had firms maintained pre-pandemic margins, inflation would likely have been lower (though shortages might have persisted longer). In sum, corporate pricing behavior amplified the inflation surge, especially early on, which further skewed the distribution of benefits away from workers and toward shareholders during this period.

Globalization, Labor Outsourcing, and the Wage Squeeze

Underlying the current mismatch between prices and pay is a longer-run structural factor: globalization and the way it has shaped wages and prices over decades. For roughly 30 years prior to the pandemic, the integration of low-cost labor from countries like China, India, and Eastern Europe into the world economy had a profound disinflationary effect. Global supply chains allowed companies to produce goods more cheaply overseas and import them, keeping consumer prices low (especially for manufactured goods). At the same time, this put downward pressure on wages for certain workers in high-income countries, as jobs could be outsourced or competition from imports restrained pay increases. In short, globalization tended to mean lower prices but also sluggish wage growth for many middle and low-skill workers in developed economies.

Economists have documented that as trade expanded, inflation dynamics changed. Increasing trade integration and the participation of low-wage producers in global production exerted a direct disinflationary effect on advanced economies. Cheap imports from China, for example, held down prices of everything from clothing to electronics for U.S. and European consumers (often dubbed the “Walmart effect”). Moreover, global competition reduced the pricing power of domestic firms – they couldn’t easily raise prices if a foreign competitor could undercut them. One European Central Bank analysis noted that trade globalization decreased the average mark-ups of domestic firms and reduced wage growth in importing countries. Essentially, companies faced tougher competition and had access to cheaper labor abroad, so they kept costs and wages low to stay competitive, and passed some of those cost savings to consumers as lower prices.

At the same time, globalization eroded the bargaining power of many workers in advanced economies. Manufacturing workers in Michigan or Sheffield suddenly found themselves competing (indirectly) with workers in China or Eastern Europe earning a fraction of the wages. This contributed to the well-documented stagnation of real wages for middle-class jobs in the U.S. and UK since the 1990s. Labor’s share of national income fell in many countries during the high-globalization era, while capital’s share (profits) rose. Unions also lost leverage as employers could threaten to offshore or automate jobs. The result was a period of low inflation and low wage growth – good for price stability, not so great for many workers’ living standards. Consumers benefited from cheap goods, but as workers they didn’t see robust pay increases.

Now, how does this relate to the recent inflation and wage disconnect? The legacy of globalization meant that going into the pandemic, workers’ wage gains were modest and often lagged productivity gains (except at the very top of the skill ladder). When the pandemic struck, some of the pillars of globalization wobbled – international trade faltered, countries realized the vulnerabilities of long supply chains, and talk of reshoring production or “decoupling” from China grew. If we are entering an era of partial de-globalization or higher trade frictions, that could remove some of the dampening effect on prices (making inflation higher) while potentially giving workers slightly more bargaining power (as labor markets tighten domestically). However, these shifts are slow-moving. In the short run, what we observed was that even during the inflation spike, globalization’s long-run imprint on wages persisted. Companies still had the option to source cheaper inputs globally or automate instead of granting big raises. And indeed, outside of a few sectors, we did not see a generalized wage-price spiral.

One example: manufacturing wages in the U.S. remain relatively subdued. As of late 2025, average hourly earnings for production workers in manufacturing were growing around 3.9–4.1% annually, which is not high by historical standards (and barely keeping up with current inflation). The fact that goods production can be done in multiple locations around the world puts a lid on how much domestic factory workers can demand – if wages rise too much, production might shift elsewhere or companies invest in automation. Trade and global supply chains also mean that inflation is more synchronized globally – a boom in one region can transmit inflation elsewhere through import prices. During 2021–22, this meant U.S. inflation (partly driven by stimulus-fueled demand) spread via higher import prices to trading partners, and conversely, Europe’s energy inflation spread to others through natural gas and oil markets.

However, globalization did not prevent the inflation surge – far from it, because the shocks were global. What it did do was influence who feels what. For instance, highly traded goods had low inflation pre-COVID, but then supply chain breakdowns flipped that script, causing a jump. Services (which are less offshorable) started to see wage pressures in 2022 in areas like hospitality, as domestic labor shortages emerged. Interestingly, the pandemic momentarily gave lower-wage service workers more leverage (due to labor shortages and stimulus boosting demand for their services). This led to unusual gains for some historically underpaid roles: between 2019 and 2023, real wages of low-wage U.S. workers (10th percentile) jumped by 13.2%, outpacing higher-wage groups. Policies like enhanced unemployment benefits, stimulus checks, and higher local minimum wages, combined with worker shortages, created conditions for pay raises at the bottom. Restaurants, for example, had to offer higher pay to attract staff in 2021–2022. Leisure and hospitality job stayers saw double-digit annual pay increases during that period – the only sector where that was true.

But even those gains, while notable, must be viewed in context. First, many low-wage workers were starting from such a low base that a double-digit percentage increase still left their wages not far above subsistence. And inflation ate into those gains; a 13% real increase over four years is good, but these workers remain among the most vulnerable to price hikes. Second, middle-wage workers didn’t see such dramatic raises, and high-wage workers saw modest growth (the 90th percentile wage grew ~4% real from 2019–2023). So inequality narrowed slightly during this unique period, but the overall wage distribution still reflects decades of global and technological pressures. In fact, despite recent gains, “nowhere can a worker at the 10th percentile earn enough to meet a basic family budget” according to EPI’s analysis. That speaks to how inadequate wage levels were to begin with, thanks in part to the prior forces of globalization and weak labor standards.

Globalized production also means that inflation and wages can diverge by sector. Highly tradable sectors like manufacturing and retail have to keep prices competitive internationally and have more access to outsourcing, which restrains wages. More local sectors (like healthcare or hospitality) can have more wage pressure if local labor is tight, but those often weren’t tradable and so did not benefit from globalization’s price dampening in the same way. During 2021–22, goods inflation spiked largely due to global factors, whereas wages in goods-producing sectors did not spike similarly. In services, wages in some niches rose (e.g. tech sector and finance had strong pay until late 2022, and low-end services saw jumps due to labor shortages), which eventually fed into service inflation, but that took time.

In summary, decades of globalized production kept prices low and wages stagnant for many workers, creating an environment where when inflation finally did hit, workers didn’t have a cushion of high wage growth or robust bargaining power to offset it. Global competition is one reason why companies felt comfortable raising prices (their costs from overseas suppliers went up, so they passed it on) yet remained resistant to raising wages until they absolutely had to. Now, with some retreat from globalization possibly underway (e.g. reshoring certain industries, or higher tariffs), there’s speculation that inflation could run structurally higher (because production costs will be higher domestically) while wages could benefit somewhat from more localized production. But those effects are in early stages. What we saw in this cycle is that globalization’s legacy – cheap goods, outsourced labor – was interrupted and reversed in pricing (leading to inflation), but the wage suppression didn’t reverse as much. Global factors still restrained an all-out wage-price spiral. Thus, globalization contributed to the dissonance: prices reacting strongly to global shocks, wages responding weakly due to global labor competition. Workers in many countries thus face the worst of both worlds: high living costs and paychecks that have long been under pressure from global labor arbitrage.

An Uneven Burden: Inflation’s Winners and Losers

Inflation is often called the “cruelest tax” because it eats away at everyone’s purchasing power, but crucially, it does not hit everyone equally. The recent bout of inflation has been felt unevenly across income levels, regions, and demographic groups, exacerbating existing inequalities. In effect, the pain of rising prices has been far more acute for some households than others. Let’s break down who has suffered more, and why.

By income class, inflation has a regressive effect. Lower-income households tend to experience higher effective inflation rates than wealthier households. This is because spending patterns differ: families living paycheck to paycheck spend a larger share of their budget on essential items like rent, groceries, utilities, and gasoline – categories which have seen some of the largest price increases. Wealthier households spend more on discretionary items or investments, and a smaller fraction on necessities. During 2021–2023, necessities had outsize inflation. For example, by late 2022, food prices were up over 10% and rents roughly 7–8% year-on-year, far above overall inflation in some prior years. A poor family that spends, say, 40% of their income on rent and utilities and 20% on food is heavily exposed to those increases. In contrast, a high-income family might spend only 20% on rent/utilities and, say, 10% on food, with more of their budget going to things like travel or entertainment (some of which were less affected by inflation initially).

Bureau of Labor Statistics data confirms this disparity. The lowest-income quartile of households spends about 35% of their budget on housing (rent) and a much larger share on food at home and basic utilities than the top quartile. In contrast, the richest households spend more on things like recreation, dining out, travel, and have more room to cut back or substitute items. During the recent inflation, the lowest income households consistently faced higher inflation rates than the national average, while the highest income households faced slightly lower than average inflation. One study found that by the end of 2022, households in the bottom 40% income bracket had the highest inflation rate year-over-year, whereas the top income bracket had the lowest. That means the poor were losing purchasing power faster.

Additionally, low-income families have fewer coping mechanisms. They often can’t easily switch to cheaper alternatives because they already buy the cheapest goods. The Dallas Fed noted that when prices rise, middle-income households might trade down to store brands or delay some purchases, but low-income households “do not have the same flexibility; in many cases, they are already consuming the cheapest products.” They also are less likely to buy in bulk or stock up before expected price hikes – simply because they lack extra cash or storage. And critically, they have smaller financial buffers (savings) to absorb a period of higher prices. The result, as surveys showed, is that inflation caused severe financial stress for lower-income Americans. Nearly half of all surveyed Americans in late 2022 said they felt “very stressed” by inflation, but this share was much higher among low-income respondents than high-income ones. For wealthier folks, inflation might mean a reduction in discretionary spending or smaller investment returns; for poorer folks, it can mean choosing which bill not to pay, or skipping meals.

By region and location, inflation’s impact has varied as well. Within countries, some areas saw faster price rises than others. In the U.S., for instance, Sunbelt cities like Phoenix, Atlanta, and Tampa had inflation rates several points above the national average at certain times, largely due to rapidly rising housing costs and strong demand influxes. Phoenix at one point in 2022 registered over 12% inflation year-on-year – partly a result of a hot housing market and more people moving there, driving up rents. Meanwhile, some Northeastern cities had slightly lower inflation. Rural versus urban differences also exist in specific cost categories: rural households might drive longer distances (so high gas prices hit them harder) but many own their homes (so they avoid the surge in rents, though they face higher utility/energy costs for heating larger homes). Urban low-income renters, conversely, got hit by big rent hikes. Europe saw regional variations too – e.g., Baltic countries experienced over 20% inflation at peak (due to energy dependency and smaller economies), whereas some others were lower.

Globally, lower-income countries generally experienced higher inflation and more hardship relative to their means. Many developing nations entered 2022 with weaker recoveries and less fiscal space. When food and fuel prices spiked, these countries faced acute crises because food can be 40% of consumer spending in such economies (versus, say, 10–15% in advanced economies). Countries like Egypt, Nigeria, and Pakistan saw food inflation cause real suffering, even if their official headline inflation might not always appear as high as in some richer nations with broad-based price increases. There were also extreme cases like Turkey and Argentina, which had their own monetary problems and ended up with inflation over 70–80% in 2022, utterly dwarfing wage growth and plunging many into poverty. In such cases, inflation wasn’t just a hardship – it was a social and political upheaval.

Demographics and specific groups have also seen uneven effects. Seniors on fixed incomes, for example, can be very vulnerable to inflation. A retiree living off a fixed pension or savings suddenly finds their income buys much less; they can’t easily go back to work to compensate. Social Security in the U.S. is indexed to inflation (with a lag), so retirees did get a big cost-of-living adjustment of 8.7% in 2023 – but that came after they had already suffered through the high inflation of 2022. Not all pensions are indexed, so some seniors effectively got poorer. Younger individuals, conversely, often have more flexibility – but younger families with kids faced high costs for items like baby formula (which had its own shortage/inflation issues) and childcare. In 2022, childcare and nursery school costs rose significantly in many places as those services faced labor shortages and had to raise wages to retain staff.

Families with children also felt the pinch of housing inflation if they needed more space. By contrast, some older homeowners who had locked in low mortgage rates were somewhat insulated from housing inflation (their payments stayed the same while market rents soared). Homeowners in general fared better than renters – inflation in home prices benefitted those who owned an asset (their home value rose), whereas renters saw nothing but higher outflows. Between demographic lines, Black and Hispanic households in the U.S. are disproportionately renters and spend larger shares on food and energy, so they experienced higher inflation burdens on average. The Dallas Fed analysis pointed out that the survey data did not support the idea that low-income families were hurt less (as one commentator speculated); on the contrary, their data showed these groups were more stressed by inflation despite some wage growth at the low end.

There were a few “winners” in relative terms. Those with fixed-rate debts (like a 30-year mortgage at 3%) effectively saw the real value of their debt eroded by inflation, which is a form of gain – they are paying back in “cheaper” dollars. And workers in certain high-demand industries (tech, until the late-2022 downturn, or energy sector jobs, or unionized workers who negotiated big raises) kept closer pace with inflation. For instance, unionized workers in some industries secured cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) or significant pay bumps (the U.S. postal workers’ new contract in 2022 included COLAs, some manufacturing unions pushed for raises). But outside a few examples, most wages lagged. Some asset owners benefitted: real estate investors saw property values inflate and could charge higher rents (though interest rates later cut into that). Likewise, businesses with pricing power (as discussed) enjoyed high profits in inflationary times. But now, as interest rates rise, some of those gains are reversing.

In essence, inflation has acted like a tax that fell heaviest on the poor, the young renting family, the marginalized communities, and those on fixed incomes, whereas those with assets or greater flexibility could weather it better. It widened the gap between those living on the edge and those with a cushion. The public discourse around inflation often reflects a median perspective, but it’s important to note that for a sizable portion of society, the inflation of 2021–2023 was not just an inconvenience – it was a severe threat to their financial stability. Many low-income families incurred debt to cope (credit card balances in the U.S. hit record highs, with nearly 1 in 4 adults taking on debt to pay for groceries amid high prices), or they drained whatever modest savings they had accumulated during early pandemic stimulus periods. Food banks reported increased demand, and utility shutoffs rose as people fell behind on energy bills.

By late 2023, inflation was moderating, but the damage to household finances was done. And importantly, prices don’t fully fall back – a slowed inflation rate only means prices are rising more slowly, not that they’re dropping to pre-spike levels. As Fed Chair Powell observed, low-income folks get hit hardest by inflation, and that was clearly evident: it has been a highly unequal burden. Any serious policy response or relief measures thus needs to consider targeting help to those most strained – whether through indexed benefits, targeted subsidies for essentials, or other support – otherwise the legacy of this inflation will be increased poverty and inequality.

Then and Now: Lessons from 1970s Stagflation and the 2008 Crisis

To put the current inflation-wage disconnect in perspective, it’s useful to compare it to past inflationary episodes – notably the stagflation of the 1970s and the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. History doesn’t repeat exactly, but it often rhymes. Each period of high inflation has its own drivers and outcomes for wages, and examining them can highlight what’s similar or different today.

The 1970s are often invoked as the last time inflation was this high in advanced economies. Back then, inflation in the U.S. peaked at over 14% in 1980. A major catalyst was the oil shocks: in 1973 and 1979, geopolitical events (the OPEC oil embargo and the Iranian revolution) caused oil prices to skyrocket, much like the 2022 energy shock but even more dramatically in percentage terms. This led to high inflation across the board, since oil is fundamental to the economy. However, the 1970s also saw something we largely haven’t seen this time: a true wage-price spiral. In that era, many workers were unionized and had COLA clauses in contracts, meaning wages automatically rose with inflation (often with a lag). As prices rose, workers successfully demanded higher pay, which in turn raised business costs and pushed prices up further. This dynamic, combined with accommodative monetary policy initially, kept inflation entrenched. Unemployment and inflation were both high (“stagflation”), a nasty combination.

In the U.S., real wages actually did rise in the early 1970s before falling later in the decade. Workers in strong unions sometimes secured raises that outpaced inflation for a while, protecting them somewhat. But by the late ’70s, inflation was eroding real pay and only belated hefty nominal raises kept some workers afloat. It ended with the Volcker Fed jacking up interest rates to extreme levels (~20%) to break the cycle, triggering a deep recession in 1981–82. After that ordeal, inflation expectations were finally beaten down, and a long era of low inflation began.

Comparatively, today’s situation has echoes of the 1970s (an energy shock, high inflation) but differs in crucial ways. One difference is the role of wages: in the 2020s episode, wage growth has been much tamer and has lagged inflation, whereas in the 1970s wages and inflation chased each other more tightly. Union coverage is far lower now, and automatic COLAs are rare, so there was less of a built-in mechanism for wage-price feedback. Indeed, policymakers today often express relief that a 1970s-style spiral hasn’t materialized – that is, long-term inflation expectations among the public and businesses have remained relatively anchored, and wage demands (while higher than pre-pandemic) have not kept inflation accelerating. Another difference: central banks reacted faster and more aggressively this time (learning from the ’70s). The Fed started hiking in early 2022 when inflation had been high for about a year; in the ’70s, rates were not raised as quickly at first, and policymakers oscillated. That said, inflation also came down quicker this time (so far) than in the 1970s, partly due to those rapid rate hikes and partly due to unique factors like improving supply chains.

There are also parallels. Both episodes highlight the role of commodity shocks: oil price spikes were central in driving inflation in the 1970s and again in 2022. Global factors were at play (in the ’70s, the Cold War and OPEC; today, the pandemic and war in Ukraine). And in both cases, inflation proved broader and stickier than initially expected, forcing tough central bank action. For workers, both episodes have the similarity that initially real wages fell – in 2021–22, real wages dropped because nominal raises weren’t enough; in the 1970s, real wages also took a hit at times when inflation outpaced pay. However, in the ’70s many workers had mechanisms to eventually catch up (albeit at the cost of entrenching inflation). Today, most do not – which is why real wages fell more steeply and for a longer continuous period (2021–early 2023 real wages were down for many quarters straight in the U.S., the longest sustained drop on record).

Now consider the post-2008 financial crisis period – essentially the 2010s. That was the opposite problem: too low inflation. After the Great Recession of 2008–09, the global economy saw years of weak demand, high unemployment, and below-target inflation, even deflation scares. Central banks slashed rates to zero (and did QE) in that period too, but inflation remained muted because slack in the economy was huge. Wages were very slow to recover – it was a long slog before unemployment fell enough that workers saw meaningful pay increases. In the U.S., by the late 2010s, the labor market tightened and wages at the bottom did start rising, but inflation still hovered around 2%. In Europe, inflation stayed under 2% and wage growth was anemic in many countries, contributing to populist discontent of a different sort (stagnant living standards).

Comparing that to now, it’s almost inverted: then we had persistent slack and subdued prices; now we had a sudden overheating and price spike. Both are problematic. The 2010s taught central bankers to worry about getting inflation up to target (some even mused about needing higher inflation to reduce debt burdens). The 2020s humbled them with a forceful reminder that high inflation can reappear suddenly. For workers, the 2010s were frustrating because even low inflation outpaced wage growth for a while – in the early recovery, unemployment was so high that many workers saw pay freezes or cuts. Only in the last few pre-pandemic years did real wages for median workers start to show consistent gains. Many households never fully recovered wealth lost in the 2008 crisis (like home equity), contributing to a feeling of “one step forward, two steps back.” Fast forward to 2022 and many of the same people felt, “Just when things were getting better, now inflation has taken away our purchasing power again.”

In other words, one could argue broad middle-class living standards in places like the U.S. have barely improved since the early 2000s once you account for these shocks – the 2008 crisis, then the pandemic and inflation. That’s a long stagnation, which breeds discontent.

One specific contrast: after 2008, central banks did unprecedented quantitative easing (QE) and low rates, but because banks were damaged and credit didn’t flow strongly, that money mostly bid up asset prices (stocks, bonds, housing) rather than consumer prices. So we got asset inflation but not consumer inflation. Wages stayed low, inequality arguably widened as asset-owners benefited. After 2020, there was again massive QE and also fiscal stimulus that put money directly in consumers’ hands – this time banks were healthy and consumers spent vigorously. The result was actual consumer inflation, which is more politically salient and directly painful day-to-day than asset inflation. Wages rose faster post-2020 than post-2008, especially for lower earners, due to tight labor markets and direct support. But inflation rose even faster, nullifying a lot of that benefit. So ironically, despite very different initial conditions, the 2010s and early 2020s both ended up with many workers saying “we’re not getting ahead.” In the 2010s it was because wage growth was too slow (though prices were stable); in the 2020s it’s because wage growth sped up but prices sped up more.

Another historical episode: the early 1980s disinflation. When Volcker’s Fed crushed inflation with high rates, it caused back-to-back recessions. Unemployment shot up to ~10%. That was extremely painful for workers (millions lost jobs), but once inflation was tamed, the stage was set for a long expansion where wages and prices were relatively stable. The lesson there was that taming ingrained inflation may require short-term pain. Policymakers today are trying to avoid a repeat of that severe cure, hoping to achieve disinflation with a softer landing (so far, by late 2023, the U.S. has slowed inflation to ~3-4% with only a slight uptick in unemployment, suggesting maybe a less brutal outcome than 1981–82). Europe and others face similar balancing acts.

In sum, history provides cautionary tales. From the 1970s, we learn the importance of not letting inflation expectations and wage-price spirals get out of hand, because the remedy is harsh. The current episode so far avoided the full spiral – wage growth never approached inflation, and now inflation is coming down, meaning a classic 1970s spiral has been averted, albeit at the cost of a period of falling real wages. From the post-2008 period, we’re reminded that low inflation/weak demand carries its own problems – and that big demand stimulus can pull us out of that, but if overdone can swing to the opposite extreme. Policymakers essentially erred on different sides in 2009 (too little stimulus leading to slow recovery) versus 2021 (arguably too much stimulus contributing to high inflation).

For workers, perhaps the silver lining is that the current high inflation did coincide with one of the tightest labor markets in modern times – unemployment hit 50-year lows – which gave some leverage, particularly to low-wage workers who finally saw sizable nominal raises. The challenge now is: can we bring inflation fully under control without slamming the labor market into a recession? If yes, workers might be able to hold on to those nominal gains and see their real wages rise again as inflation falls. If no, we might repeat a cycle of job losses and another slow recovery. History’s lesson is that once high inflation is beaten, the subsequent period can be good for real income growth (as in the later 1980s and 1990s). But getting there is fraught with risk. Policymakers today are navigating between the ghosts of the 1970s (don’t let inflation stay high) and the ghosts of 2008 (don’t crush the economy unnecessarily). The outcome will determine whether today’s workers see their living standards recover or face a prolonged squeeze.

Wages vs. Inflation Across Sectors: A Tale of Two Economies

Not all workers and industries have experienced the inflation and wage situation identically. There’s a stark contrast between different sectors of the economy – for example, services vs. manufacturing, or high-paying industries vs. low-paying ones – in terms of how wages have trended versus prices. Understanding these nuances gives a clearer picture of why some people might feel better off (or at least not worse off) while others feel left behind.

Consider the service sector (encompassing everything from hospitality and retail to healthcare and education) versus the manufacturing sector (factories producing goods). During the pandemic recovery, demand shifted more toward goods initially (people bought exercise bikes instead of gym memberships), then later swung back toward services (travel, dining out, concerts once vaccines came). This meant the pressures on wages and prices also shifted.

Manufacturing and goods-producing industries faced massive supply chain issues that drove up prices of their outputs (as we discussed), but many manufacturing firms managed to do so without equally large increases in labor costs. Why? Partly because manufacturing employment did not recover as robustly – output came back with fewer workers, thanks to automation or offshoring or productivity boosts. Also, manufacturing is globally competitive, so although product prices rose, there was a limit to wage hikes because companies could move production or automate if domestic wages jumped too much. As a result, manufacturing wage growth was moderate. As noted earlier, manufacturing average hourly earnings were rising around 3-4% annually in recent times, which lagged inflation in 2021–22 (so real wages fell), though by 2023 as inflation cooled, those wage gains turned into slight real improvements. But broadly, manufacturing workers did not see huge nominal raises during the inflation spike; many essentially treaded water or lost a bit in purchasing power.

In contrast, some service industries – especially those with historically low wages – saw much sharper pay increases because of acute labor shortages. The poster child is leisure and hospitality (restaurants, bars, hotels). This sector was decimated in 2020, then experienced a crazy rebound in demand and a shortage of willing workers (many workers left during COVID and were slow to return, plus competition from other jobs and some reluctance to work in public-facing roles due to health concerns). Employers had to hike wages significantly to attract staff. The data is striking: Leisure and hospitality wages for new hires jumped about 38% from 2018 to late 2024, with much of that occurring after 2020. Even for existing employees (job stayers), leisure/hospitality saw double-digit annual wage growth in late 2021 through 2022 – something virtually unheard of before. For example, many restaurants raised their starting pay from, say, $10–12/hour pre-pandemic to $15–18/hour or more by 2022, due both to market forces and increases in local minimum wages in many states.

These wage hikes in services contributed to services inflation, particularly in categories like dining out, hotels, and personal services. Restaurant menu prices climbed as businesses passed some of their higher labor costs (and food costs) onto customers. By 2022, inflation in services (excluding energy) had picked up to around 5-6% in the U.S., the fastest in decades. This was driven in part by wages: whereas goods inflation was largely supply-driven, services inflation is more closely tied to labor costs. Research from the Peterson Institute noted that service prices closely follow wages, whereas goods prices are more driven by supply factors. So as wage growth in services accelerated in 2022, service inflation also rose, even when goods inflation started to cool.

However, importantly, those service sector wage gains, while large in percentage terms, often just brought low-wage workers a bit closer to a living wage rather than putting them ahead of inflation. For instance, a hotel housekeeper’s hourly wage might have gone from $12 to $15 (25% increase), but if their rent and grocery bills went up 15% and 12% respectively over the same period, their improvement in real terms was modest. EPI highlighted that despite these strong gains, low-wage workers still generally earn too little for basic needs.

Higher-wage service industries (like tech, finance, professional services) initially saw strong demand and wage growth as well (tech companies were bidding up salaries to attract talent in 2021, finance bonuses were huge after a booming market, etc.). But by 2022–23, some of those industries cooled dramatically – tech, for example, went from labor shortage to significant layoffs as interest rates rose and stock valuations fell. Wage growth in those sectors slowed or even reversed for some (with smaller bonuses, etc.). Yet these workers often have savings or assets to buffer inflation, so their consumer impact is different.

Public sector vs private sector is another split: many government workers, such as teachers or civil servants, have pay scales that adjust slowly and often lag market rates. During 2021–22, a lot of public employees got meager raises (if any) because budgets were tight or bargaining was slow, meaning they lost considerable purchasing power. Some quit for private jobs, exacerbating shortages (e.g., nurses leaving public hospitals for private agencies). Eventually, some governments started approving larger raises (some teacher unions negotiated 5-8% raises in 2022 or 2023 to catch up), but by then inflation had already eaten into their earnings.

Unionized vs non-union sectors also diverged. Unions in sectors like trucking, airlines, and manufacturing (auto workers, etc.) saw their collective agreements coming up for renewal in 2022–23 and pushed for big raises, citing the high cost of living. Many succeeded in winning historically large pay increases. For example, in 2023 the United Auto Workers negotiated a deal with the Big Three automakers including wage hikes of roughly 25% over the contract plus cost-of-living adjustments – a direct response to the inflation that had occurred. This means those workers will likely outpace inflation going forward (if inflation stays moderate). But these gains came after the fact; in 2021–22, those same workers’ real pay had declined (their previous contracts had smaller raises that were wiped out by inflation). Non-union workers, unless in very in-demand roles, often had less leverage to demand inflation-matching raises and many simply had to tolerate the loss in purchasing power.

Sectoral inflation differences also matter. Housing-related sectors (construction, real estate) saw booming prices – home prices and rents soared – but construction worker wages did not skyrocket to the same degree. They rose, certainly (construction jobs were plentiful), but home prices were more driven by low interest rates and material costs than labor costs. Healthcare saw high labor cost growth (nurse shortages led to rising pay for travel nurses, etc.), contributing to rising medical services inflation (though measured healthcare inflation in CPI was modest in 2021–22, partly due to how it’s calculated). Education sector wages were quite stagnant, but college tuition still went up (though not as much as some other things).

It’s illustrative to think of two economies: one, the low-wage service economy (restaurants, retail, caregiving, hospitality), which in 2021–22 experienced unusual wage growth due to labor scarcity – essentially a partial correction of decades of stagnation – but is also very sensitive to inflation in essentials. The other, the goods-producing and high-end service economy, where wages grew more slowly or even faced cuts (in inflation-adjusted terms), but companies had high profits and pricing power. In the first, workers gained some ground nominally, yet still struggle with costs; in the second, workers didn’t gain much ground, but many companies did well until higher interest rates slowed demand.

A concrete example: grocery store workers vs grocery prices. Grocery prices (food at home) were up about 12% in 2022. Did grocery store employees get 12% raises? Not typically – many are low-wage and non-unionized (except in some cities). They might have gotten perhaps 4-5% raises. So even in the very sector where prices soared, the front-line workers saw real wage drops. Meanwhile, large grocery chains saw strong sales and in some cases higher profits because they could pass on supplier cost increases plus a bit more.

Another example: airlines. Airfares jumped as travel demand returned and fuel prices rose, plus limited flight capacity. Airline pilots and crews, many unionized, leveraged the situation to win big raises (pilots got contracts with 20-40% increases over a few years in 2023). So here, a sector had high inflation (ticket prices) and eventually also high wage growth – but one could argue wages were catching up for pilots after a weak 2020 when many took cuts. Still, pilots likely will stay ahead of inflation going forward because of those raises.

In summary, the inflation vs wage story has been highly sector-specific. Services generally saw higher wage growth than goods, yet services inflation also picked up due to those wage gains and other factors. Goods industries saw high prices but moderate wage gains. Low-wage sectors saw the biggest nominal wage jumps (long overdue, one might say), but because those sectors’ workers spend most of their income on necessities, they still often fell behind in real terms. The broad outcome was that very few sectors saw real wage growth keep pace with the spike in prices – perhaps only a handful of niche fields or those who renegotiated salaries at just the right time. By late 2023, average wage growth in many countries finally edged above inflation (with inflation coming down), meaning a return to real income growth. For instance, U.S. average weekly wages grew about 4.2% year-on-year in mid-2025 while inflation was ~2.7%, a modest real gain. But that was after a cumulative real wage loss in 2021–22.

Looking ahead, the question is whether sectoral differences will persist. Will those hospitality and retail wage gains stick (and continue) even as the labor market cools? Will manufacturing and tech wages rebound if inflation ebbs and demand picks up? Early signs suggest that the lowest-paid workers may hold onto much of their raises – companies are not broadly cutting pay – though the pace of further increases is slowing. That means relative inequality between sectors narrowed slightly during this period (janitors got closer to parity with higher earners, relatively speaking, as one analysis showed wage gaps between groups narrowed). But inflation basically “paid for” that narrowing by knocking down everyone’s real incomes – a Pyrrhic victory of sorts for equality. In an ideal scenario, wage growth could remain solid while inflation comes down, allowing real incomes to rise, especially for those who fell behind. Whether that happens will vary by sector and depend on broader economic conditions.

For now, it’s clear that different industries had very different experiences of the inflation shock – some saw profit booms and limited wage pressure, others saw wage spikes and cost pressure. Any worker’s personal situation depended a lot on what sector they were in. The overall narrative of “prices outpacing wages” holds true, but beneath it lies a mosaic of mini-stories.

The Cost-of-Living Squeeze: Housing, Food, Transportation, and Healthcare

To truly grasp the burden inflation has placed on households, it helps to zoom in on the everyday expenses that make up the cost of living. Over the past couple of years, the prices of life’s essentials – shelter, food, transportation, healthcare – have all climbed, squeezing family budgets. Even where wages rose, those gains often evaporated when paying the monthly rent or filling up the gas tank. Let’s examine each of these key categories:

Housing Costs (Rent and Mortgages)

For many families, housing is the single largest expense – and it’s one that has seen relentless inflation. Home prices and rents surged dramatically during the pandemic period. Initially, record-low interest rates and a desire for more space drove a housing price boom: by 2022, U.S. home prices were roughly 40% higher than pre-pandemic levels in many areas. That created huge equity gains for homeowners, but for buyers it meant stretching further (and then facing higher mortgage rates in 2022–23).

Renters felt the crunch as well. After a brief dip in 2020 (when urban rents fell due to remote work), rents rebounded and then some. Nationwide U.S. rents rose about 10–15% in 2021 and another 5–10% in 2022, depending on the measure – some of the fastest rent increases on record. The Consumer Price Index’s rent measure (which lags real-time rents) showed rent inflation of around 7–8% in late 2022, the highest since the 1980s. For context, that means a tenant paying $1,000 would be paying $1,080 a year later on average – and many faced far larger jumps at lease renewal, especially in high-demand cities or Sunbelt regions where double-digit rent hikes were common. This kind of increase can wreck the finances of lower-income renters who budget nearly every dollar. BLS data shows the lowest quartile spends 35% of income on rent on average, so a 10% rent hike can gobble up an extra 3.5% of their income – often more than any raise they got.

The housing inflation has two painful aspects: prices shot up, and interest rates shot up. For those aspiring to buy a home, 2021–2022 was a nightmare – home prices at record highs, then mortgage rates spiking from ~3% to ~7%. The result: mortgage payments for a median home nearly doubled in some cases. This effectively pushed millions out of the home-buying market, keeping them renting (which then adds pressure to rents). Homeowners with fixed mortgages were somewhat insulated from inflation (a benefit for them), but new buyers or those with variable rates faced big cost increases.

Shelter inflation has a lasting impact because unlike, say, gas which you buy continuously, rent resets infrequently but then locks you in at a higher level. Many renters depleted savings or took roommates or moved to cheaper areas to cope. In cities like New York, rents hit all-time highs in 2022/2023, exacerbating affordability crises. Some states saw rent increases of 20-30% over a year or two (e.g., Florida, parts of the Southwest), absolutely crushing for local workers whose wages definitely didn’t rise that fast.

Housing also influences other costs: high housing costs leave less for other spending, and can increase commuting costs if people move farther out for cheaper rent. Governments responded mildly – some cities expanded rental assistance or passed rent control measures, but broad relief was limited. Higher interest rates eventually cooled the housing market – by 2023, home price growth stalled or reversed in some areas, and rent growth moderated – but the elevated price level remains. As noted, inflation easing doesn’t mean rents drop; it mostly means they rise slower. So a renter might see a 3% hike instead of 10%, but that’s still an increase on top of prior increases.

Food and Groceries

Few things hit consumers as viscerally as rising food bills. Food prices worldwide jumped sharply, driven by supply chain issues, higher transport costs, bad weather, and the war in Ukraine (a major grain exporter). By 2022, grocery inflation in advanced economies hit multi-decade highs. In the U.S., food-at-home (grocery) prices were up 12.2% year-over-year in June 2022, the largest spike since 1979. Prices for staples like meats, dairy, cereals, and fruits/veggies all climbed. Eggs, for example, more than doubled in price at one point due to an avian flu outbreak reducing supply – a carton that used to cost $1.50 became $3.50 or more, adding up for families who buy eggs weekly.

For low-income families, higher food prices forced difficult trade-offs: food is often one of the flexible parts of their budget (unlike rent or utilities which are fixed). Surveys showed many people cut back on meat, switched to cheaper generic brands (if not already on them), or outright bought less food. The Urban Institute found about 1 in 5 adults reported household food insecurity (skipping meals, etc.) in late 2022, up from before. Food banks saw increased demand as well. Even middle-class families felt sticker shock; a typical grocery trip that used to cost $100 might be $115-$120 for the same items.

Restaurant prices also rose (~8% in 2022 in the U.S.), partly reflecting the higher ingredient costs and higher wages for staff. So whether cooking at home or eating out, consumers paid more. Internationally, the situation was dire in many developing countries: countries that import a lot of wheat or cooking oil (like many in the Middle East/North Africa) experienced huge price surges that sparked protests. The phrase “cost-of-living crisis” was particularly apt for food in those locales, as some governments had to expand subsidies or risk unrest.

The good news: by mid-2023, global food commodity prices had come down from peaks and grocery inflation cooled. But again, that’s a slower increase, not a reversal. And some sticky areas remain – e.g., in the U.S., snacks and sweets continued to climb in price even after meat and produce stabilized, perhaps because companies found consumers were tolerating higher prices (linking back to corporate strategies).

Transportation (Gasoline, Cars, and Travel)

Transportation costs were another major pressure point. This includes the price of fuel, the cost of vehicles, and fares for public or commercial transport.

Gasoline prices, as discussed, hit eye-popping levels in 2022. An average American driver saw gas go from around $2.20/gal in 2020 to over $5 by June 2022. That’s more than double, directly taking a bigger chunk of budgets for commuters and anyone who drives for a living (rideshare drivers, truckers—though truckers often have fuel surcharges to pass cost on). Gas inflation was incredibly salient and politically sensitive; it alone contributed about 2-3 percentage points to overall CPI at its peak. While drivers did get some relief in late 2022 when oil prices fell slightly, by 2023 gas was still higher than pre-pandemic. People responded by driving less or carpooling where possible, but many had no choice but to pay. In Europe, natural gas for heating and petrol for cars spiked, prompting some governments to cut fuel taxes or offer rebates. The U.S. released oil from strategic reserves to try to temper gas prices.

Car prices were a unique saga. Due to the chip shortage and supply chain snarls, new car production couldn’t meet demand, so new car prices rose ~12% year-over-year at one point. But even crazier, used car prices shot up ~40% year-over-year in 2021, an unprecedented jump, making some used cars more expensive than they were brand new. This was temporary, but for a while, anyone needing a vehicle faced either long waits or exorbitant prices. Many lower-income workers rely on older used cars to get to work; seeing those prices spike meant some were priced out or had to delay purchases, keep driving very old cars, and risk breakdowns. Auto loan rates also climbed as the Fed raised rates, so the financing cost of a car went up too.

By mid-2023, used car prices had actually come down from their peak (deflating a bit), but new car prices remained elevated, and auto loan interest was much higher, so the overall cost to buy a car remained burdensome. Repair and maintenance costs also rose (parts shortages, etc.), so even keeping an old car running got pricier (e.g., the price of tires, batteries, and auto parts were all up double-digits in 2022).

Public transit and travel: many transit agencies in cities faced higher fuel and labor costs, though some did not raise fares significantly due to policy choices (or they were still trying to lure riders back post-COVID). On the other hand, airline fares in 2022 jumped ~25-30% as travel demand surged and fuel prices soared. So vacations became more expensive, which might seem discretionary, but for some workers (business travel, or visiting family) it’s meaningful. The spike moderated later, but flying remains pricier than pre-pandemic generally.

Healthcare