Luxury yachts anchored at Davos offer a stark image of the world’s wealthiest enjoying privileges far beyond the reach of ordinary Americans. Yet while those yachts gleam, their owners often pay less in taxes – proportionally – than the people who wash their dishes or staff their hotels. A 2021 analysis by the White House found that the 400 richest U.S. families paid only 8.2% of their income in federal income taxes (2010–2018). By contrast, the average American taxpayer paid about 13% of income in federal tax. In fact, one public-school teacher pointed out that in 2017 she paid $1,562 in federal tax – more than twice the $750 Donald Trump paid that year. This isn’t an anomaly: studies repeatedly show working families often shoulder a heavier tax burden (federal and otherwise) than the ultra-wealthy.

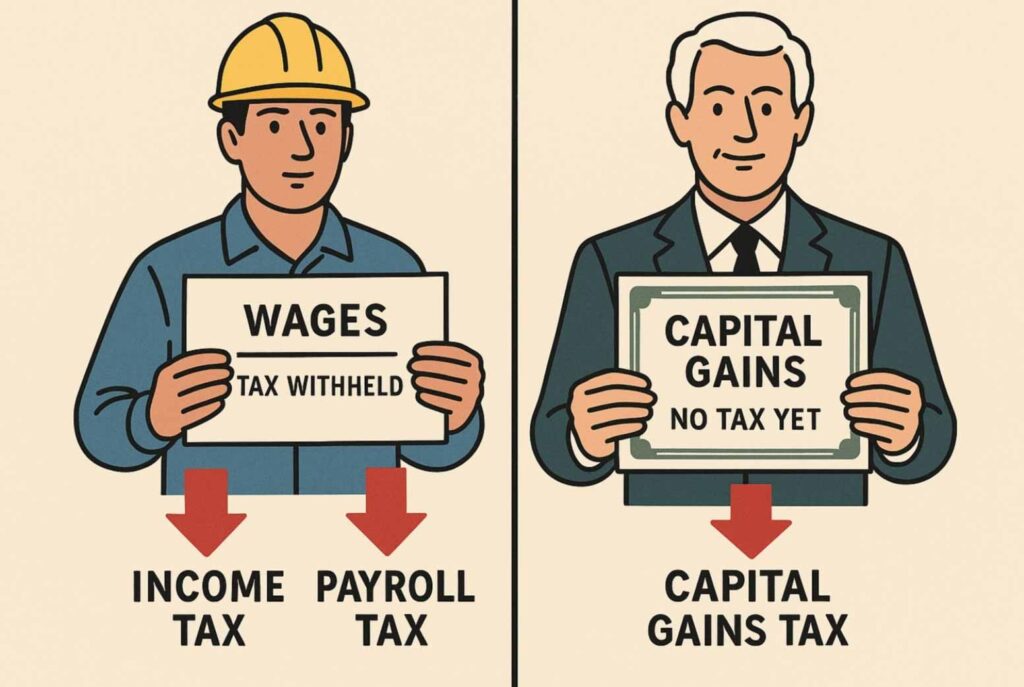

This gap has only grown as the tax code has evolved. Laws over decades have gradually tilted the system in favor of capital income (interest, dividends, stock gains) and wealth over wages. Today, lower- and middle-income Americans pay payroll and sales taxes on every dollar they earn or spend, while many of the rich earn mostly untaxed gains on assets that can be deferred or passed to heirs tax-free. In practice, this means a teacher, nurse or factory worker can end up paying a far larger share of their wages in taxes than a hedge-fund manager or tech founder pays on an equivalent cash flow.

In this deep-dive analysis we document that paradox in detail. We break down the U.S. tax burden on wage-earners versus asset-owners – from federal income and payroll taxes to sales and property taxes. We show how special breaks like lower capital-gains rates, tax-deferred accounts and stepped-up basis let the wealthy avoid taxes that fall on workers. We tell anonymized stories of everyday Americans alongside sketches of high-net-worth taxpayers. And we look back at how historical reforms shaped the current rules, as well as how other countries tax income and wealth differently. The result is an “upside-down” system: one that, on balance, takes a bigger bite from the bottom half of earners and a much smaller bite from the top. This feature will trace every corner of that burden – with numbers, history, and real-world examples – to explain why poor and middle-class wage-earners effectively pay more in taxes, proportionally, than the richest Americans.

How U.S. Taxes Are Split Between Wages and Wealth

The U.S. tax system has many parts: federal income taxes (progressive), Social Security/Medicare payroll taxes, state income taxes, sales taxes, property taxes, estate taxes and more. On paper, the federal income tax is progressive: higher wages pay higher rates. In reality, other taxes make the overall burden regressive. Wage earners face immediate taxes on each paycheck or purchase; wealth-holders often defer or avoid tax for years. For example, imagine two Americans who each see $1,000 of income in a year. A cashier earning that as salary owes payroll and income tax immediately, along with sales tax on purchases made with it. An investor who simply holds $1,000 worth of stock that appreciates by $1,000 owes no tax at all until (and unless) she sells that stock. That deferral can stretch for years – and if she never sells and instead dies, the gain can pass to heirs entirely untaxed under today’s “stepped-up basis” rules.

To see the overall effect, analysts compare effective tax rates (total taxes paid divided by income) across income groups. The findings are striking:

- Federal income tax: If we look strictly at federal income taxes on reported taxable income, higher earners do pay higher marginal rates (37% top bracket today). But when all taxes and all income are counted, the rich often pay less. For instance, White House economists found the top 400 richest families paid just 8.2% of their income in federal income tax – far below the 13% average among all taxpayers. (That analysis counts not only wages but also unrealized stock gains as “income,” making it clear how much of the rich families’ wealth growth goes untaxed.) Other studies confirm that some billionaires’ effective tax rates on total wealth gains are lower than those of ordinary workers when all factors are included.

- Payroll taxes (Social Security/Medicare): These are flat taxes on wages (12.4% SS + 2.9% Medicare on earnings up to a cap). Because Social Security taxes stop above ~$160,000 (2023 cap) and Medicare above $200k earns only a small 0.9% extra, very high earners pay a tiny portion of their total income in payroll taxes. By contrast, low-income workers pay the full rate on every dollar. One analysis found that Americans making under $10,000 effectively pay 14.1% of their income in payroll taxes, while those making over $1 million pay just 1.9%. (Once that high earner hits the Social Security cap, almost all additional earnings escape payroll tax.)

- State and local taxes: Most states levy sales taxes and some levy income taxes. Both tend to be regressive: states like Louisiana and Texas (with no income tax but high sales taxes) squeeze poor households more. A report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that in the ten most regressive states, the poorest 20% of households pay three times as much of their income in state and local taxes as the richest 1%. Nationwide, the poorest quintile pays roughly 11.4% of income in state/local taxes, versus 7.4% for the top 1%. In practical terms, that means low-wage families shell out a larger share of their paychecks on sales and property taxes than the very wealthy do.

Overall, studies conclude that the combined state and local tax system is often “upside-down”: it asks more from those earning the least and less from those at the top. In 41 states the wealthiest pay lower state taxes on average than middle-income families. Because poor and middle earners spend a higher proportion of their income on consumption (food, clothing, gas), sales taxes hit them hardest. By contrast, the rich often rent out properties or live off investment gains, which face lighter or no sales tax.

Federal Payroll Taxes: A Hidden Regressive Levy

One of the most burdensome taxes for working Americans is the payroll tax funding Social Security and Medicare. Unlike income tax, it is levied at a flat rate on wages up to a cap. In 2024, workers pay 6.2% Social Security tax on wages up to $168,600, plus 1.45% Medicare tax on all wages (with an extra 0.9% on wages above $200,000). Employers match these contributions. In effect, every $1 earned by an entry-level worker faces the full 7.65% employee payroll tax (plus a mirror amount from the employer), whereas an extra $1 earned by a millionaire above $168k faces no Social Security tax and only the tiny additional Medicare rate.

This creates a strongly regressive effect. As the Center for American Progress explains:

- Low earners pay ~14%: Americans earning under about $10,000 end up paying around 14.1% of their income in combined payroll taxes (counting both the employee and employer halves).

- High earners pay ~2%: By contrast, those with millions of dollars in wages see their effective payroll tax rate drop to just 1.9%. Once a high-income worker exceeds the Social Security cap, nearly all further earnings are free of the 12.4% Social Security levy.

Thus the payroll tax, which looks flat, actually hits the poor the hardest. In raw dollars a millionaire pays a lot, but as a percentage of income it is small. Meanwhile, a low-wage worker pays the same 6.2% up to the cap, making it a far larger share of a modest paycheck. (Families with multiple low-earners also have each wage taxed similarly.) The regressive nature of payroll tax means that working families have fewer dollars to spend on essentials, even as the wealthy dodge much of this tax.

State and Local Payroll Taxes: Many states also impose payroll-like taxes for unemployment insurance or disability. These too often have caps and flat rates. The combined picture is that ordinary workers get hammered by every paycheck, while wealthy people’s income often escapes much of these levies.

Federal Income Taxes: Progressive on Paper, Preferential in Practice

Federal income tax law has a progressive rate schedule (from 10% up to 37%), along with deductions and credits aimed at low- and middle-income families. But several features blunt its progressivity:

- Capital gains and dividends taxed lower: Long-term investment gains and qualified dividends face a top rate of 20% (plus a 3.8% Medicare surtax for very high incomes), far below the 37% top rate on ordinary wages. In practice, this means two high earners with $1 million each can owe very different taxes: one earning wages pays up to 37% on each extra dollar, whereas one earning $1M from stock sales pays at most 20%. As the Institute for Policy Studies notes, this gap allows the richest Americans to pay “a small share of total U.S. taxes” relative to their income. Indeed, for the richest filers the effective tax rate on capital income can be well under 20% after deductions – far below the rate on wages.

- Uneven distribution of investment income: A tiny sliver of Americans captures most of the capital gains and dividends. The richest 0.5% of taxpayers receive roughly 70% of all long-term capital gains and about 43% of all qualified dividends. By contrast, households earning less than $40,000 account for only about 0.4% of gains and 1.2% of dividends. In dollars, that means almost all of the $700+ billion in stock-market gains each year go to the wealthiest Americans. Lower-income households live mainly off wages (78% of income from wages for under-$100k families) and get almost no benefit from the low 15–20% tax rates on profits.

- Large deductions favor the rich: Certain tax breaks mostly help those with higher incomes. For example, before its cap change, the SALT deduction (for state and local taxes) was claimed by 75% of taxpayers with incomes over $1 million but by under 1% of those under $30,000. The mortgage interest deduction similarly skewed rich: in recent years the top 1% claimed an average $13,000 deduction each year, whereas those earning under $10,000 got only about $33. By reducing taxable income, these deductions shrink the effective rate paid by the wealthy.

- Low estate and gift taxes: Only the very richest estates pay any estate tax at all (exemption ~$13.6M per person in 2024). Most unrealized gains in estates are wiped out by the “stepped-up basis” rule – heirs inherit property with its value reset to market at death, so decades of gains escape tax. In short, billionaire fortunes can grow largely tax-free across generations while middle-class estates face no such advantage.

The combined effect is that tax rates on capital and wealth are far lower than on wages. A 2021 CAP study bluntly states: “wages are taxed at higher rates than income derived from wealth and [our] tiered rate system benefits the richest Americans”. This point is echoed in headlines: “The Forbes 400 Pay Lower Tax Rates Than Many Ordinary Americans,” noting the ultra-rich’s ~8.2% rate vs much higher rates for workers. Warren Buffett famously explained in 2011 that his 17.4% tax rate was lower than any of his employees’ rates (who averaged ~36%). These are not aberrations but predictable outcomes of our tax rules.

Key Tax Code Breaks: How Wealth Rolls Up Advantages

Several discrete features of the tax code, taken together, generate the “upside-down” burden on workers and wealth. Among the most important:

- Flat/Regressive Payroll Taxes: Social Security and Medicare levies fall heaviest on middle- and low-income labor. (There are no analogous payroll taxes on dividend or interest income.)

- Preferential Capital Income: Investment returns (stock gains, interest, rent, etc.) face lower tax rates and often escape tax entirely until realized. Assets sold after a year pay at most 20%, versus 37% on wages. Even those high earners who do pay the 20% rate accumulate wealth under tax-deferral regimes.

- Special Deductions: Breaks like the SALT and mortgage deductions, and the pass-through business income deduction, overwhelmingly benefit the rich. These lower the top incomes’ tax bills far more than average taxpayers’.

- Deferred and Exempt Gains: Because capital gains are taxed only when realized (sold), wealthy owners of appreciating assets can postpone tax indefinitely. Importantly, if they never sell and hold onto assets until death, the gains often escape taxation under stepped-up basis. One analysis notes, “unrealized capital gains are the main form of income for some very wealthy people,” allowing them to pay no income tax on most of their true income.

- Estate and Gift Leverages: Under current law, heirs pay no tax on unrealized gains (stepped-up basis), and only a tiny fraction of estates ever pay the federal estate tax at all. In effect, fortunes can pass to the next generation largely tax-free, compounding wealth without corresponding tax burdens.

These breaks mostly flow to the top. For example, a CAP analysis found that roughly 70% of all reported capital gains (taxable as capital income) go to the richest 0.5%. Similarly, analysis shows that around 69% of “pass-through” business income (income earned via partnerships, LLCs, etc.) ends up in the top 1%. By contrast, lower- and middle-income households derive almost all their income from wages, pensions and small business earnings, which face higher rates and immediate taxation.

In sum, wealthy taxpayers play by different rules. They often leverage legal tools to transform wages into investment income, borrow against untaxed gains, and delay tax indefinitely. As FactCheck.org noted in 2023, “many billionaires pay lower tax rates than schoolteachers… if you count the unrealized gains” – gains that middle-class Americans would have to recognize and tax on immediately. Under the current system, the effective outcome is that millions of working households pay a far higher fraction of their income in taxes than the ultra-rich do in practice.

Breaking Down the Burden on an Ordinary Worker

Consider a composite example (informed by real data): Maria is a single mother earning $40,000 per year as a school custodian. Federal income tax on her taxable income might be roughly 10-12%. Her payroll taxes (Social Security + Medicare) take about 7.65% of each paycheck (half withheld by her employer). A 5% state income tax might take another few hundred dollars. She pays sales tax (say 6-7%) on groceries, clothing and fuel. Altogether, Maria could spend around one-quarter to one-third of her gross income on taxes at various levels. If she rents an apartment, she still pays property tax indirectly through rent. There is little she can do to avoid these taxes – withholding is automatic, and sales tax is embedded in every purchase.

Now imagine Samuel, a retiree who lives on investment income. Samuel earned much of his wealth decades ago. In recent years he has taken no salary, but his stock portfolio and rental properties have appreciated. Because he doesn’t sell the properties, those gains are unrealized and untaxed. He occasionally sells a few mutual fund shares, realizing $10,000 of capital gains, on which he pays roughly 15–20% tax ($1,500–$2,000). He pays no payroll tax (since he has no wages) and likely minimal state tax on investment income. When Samuel dies, his heirs will inherit the assets at current market value, with no tax on all the appreciation he earned in life. In total, Samuel may end up paying only a few percent of his wealth’s growth in taxes each year – far less than the fraction Maria pays on her wages.

This hypothetical mirrors countless real cases. A New York teacher bluntly illustrated it after the 2020 election: she paid more in federal tax in 2017 than Donald Trump did that same year. Warren Buffett, in 2011, calculated that his 17.4% tax rate was lower than any of the 20 employees he had, whose rates averaged 36%. When Washington state passed a capital gains tax in 2021, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos quickly moved to Florida and then sold billions in stock – saving an estimated $288 million in taxes by avoiding Washington’s levy. These stories underscore how legal tax strategies allow the wealthy to pay far less than ordinary earners.

For contrast, Congress recently estimated that the poorest 20% of households pay about 5–6% of their income in federal taxes, while the top 1% pay around 30%. (Those numbers include payroll tax and income tax.) But that conventional view doesn’t count all wealth income. If unrealized gains and wealth are counted, the vast fortunes of the richest end up paying a much smaller percentage of their true economic gains than working families do.

How 100 Years of Tax Changes Tilted the System Toward the Wealthy

The current tilt toward capital has deep roots in U.S. tax history. Throughout the 20th century, reform debates swung back and forth between taxing labor and capital. In the mid-1900s, top income tax rates were very high (over 90% in the 1950s), and the capital gains tax was often close to ordinary rates. But starting in the 1960s and accelerating in the 1980s, Congress aggressively cut those top rates and created new loopholes. For example, the Tax Reform Act of 1986 lowered the maximum tax rate on long-term capital gains from 28% to 20%. Since then, long-term gains have mostly stayed at 15–20%, while statutory top wage-tax rates eventually sank from 70+% to the current 37%. By 1962 the top marginal rate was 91%; by 2018 it was just 37%.

As top rates fell, wealth inequality surged. The rich’s share of national income climbed back to levels not seen since before the Great Depression. Cutting tax rates on the wealthy was explicitly linked to that rise in inequality. A 2021 report notes that the top 0.01% of taxpayers pay far less tax relative to their wealth today than in the 1950s–1970s. In short, policy choices – lower top rates, incentives for investment, and expanding tax shelters – have magnified the gap between labor and capital.

Today’s tax preferences are relics of that era. Congress continues to allow (and often extend) breaks like the carried-interest rule for hedge funds (treating those payments as capital gains, not wages), generous 401(k) deferrals, and little enforcement of transfer taxes on wealth. The Build Back Better proposals of 2021/2022 aimed to claw some of this back by raising capital gains rates for the very wealthy and limiting step-up basis, but as of 2025 most of those measures have not passed. Thus, the basic structure remains: capital income gets softer treatment than wages.

One stark demonstration is the “step-up in basis” at death. Experts note that when an asset is inherited, its basis is reset to market value. This wipes out all uncollected income tax on appreciation. As Tax Policy Center’s Steven Rosenthal put it: “If a wealthy investor never sells stock that has increased in value, those gains are wiped out for income tax purposes when those assets are passed on”. In other words, a $1 billion gain over 40 years can vanish from the tax rolls entirely by dying. Meanwhile, workers retire and draw down savings that have already been taxed through payroll and income tax – a double disadvantage.

Overall, the evolution of the U.S. tax code – from the Reagan cuts to the Bush tax cuts and beyond – has increasingly favored capital and the richest Americans. The current gulf between labor and capital taxation is the product of decades of policy decisions that tilted the playing field.

State-by-State and Local Taxes: Squeezing the Bottom

While federal taxes get most attention, state and local taxes amplify the burden on ordinary workers. Every state except Alaska and a few rely heavily on sales and excise taxes. These taxes are almost always regressive – poorer people spend a larger share of their income on goods like food and clothing. For example, Louisiana has one of the highest combined sales-tax rates in the U.S. (over 9.5%), and its poorest families pay a huge share of income in sales taxes, while the richest pay much less. In many states, services and essentials (like groceries, drugs, utilities) carry lower rates or exemptions, but that still leaves big-ticket items (cars, electronics) fully taxed.

Moreover, some blue states have begun taxing capital gains at the state level. Washington imposed a 7% tax on large capital gains in 2022, and California imposes tax on high earners’ stock sales. These state capital-gains taxes have drawn fierce opposition from wealthy taxpayers. When Washington’s tax went into effect, the state unexpectedly raised nearly $900 million, more than anticipated, demonstrating the revenue potential. But opposition also cited cases like Bezos’s move: by selling $4.2 billion in stock after relocating to Florida, he avoided Washington’s 7% levy and saved about $288 million. That anecdote highlights how mobile capital can evade state taxes, while workers (who rarely relocate for a few percent income tax savings) continue paying state income or sales taxes on fixed earnings.

Property taxes also play a role. They tend to be somewhat progressive at first (homeowners vs renters), but rising property values have raised taxes on many working families, especially those in growing cities. By contrast, ultra-rich individuals often own properties through trusts or LLCs, sometimes qualifying for lower tax rates and never paying sales tax on renovations. The result: many working Americans see steep local tax bills, while the wealthy often legally minimize property tax or offset it with deductions.

In total, state and local taxes (income, sales, property) capture a larger fraction of poor and middle-class incomes. One analysis found the combined state/local tax rate for the bottom quintile is about 11.4% of income, versus only 7.4% for the top 1%. This disparity stacks on top of the federal imbalance to give working people a triple hit: federal income tax (moderate), payroll tax (very high), and regressive state/local taxes. Meanwhile, wealthy citizens mostly escape payroll taxes and benefit from state tax breaks.

Global Comparisons: U.S. vs. Other Wealthy Nations

How does the U.S. pattern compare to other countries? Many industrialized nations also tax capital at lower rates than labor, though there are variations. For instance, in several European countries the top income-tax rates are even higher than in the U.S., often exceeding 50%. But these countries usually have a broad Value-Added Tax (VAT) – a consumption tax – that all consumers pay. By design, VAT is regressive on income, so Europe’s heavy reliance on VAT means the poor there also shoulder significant tax burdens on purchases. Economists note that VAT tends to tax the poor (who spend most of what they earn) more heavily as a share of income. In effect, working Europeans pay payroll taxes (typically high, up to 40% for Social Security in some countries) and consumption taxes, while capital gains rates vary.

Some European countries do tax wealth directly: as of 2025, only Norway, Spain, and Switzerland still have broad net wealth taxes, and even those raise very modest revenue. Others (France, Italy, etc.) have abandoned wealth taxes or replaced them with one-time levies. Capital income in Europe is often taxed at lower flat rates: Reuters notes that France, Germany, Italy, Japan and others tax capital gains and dividends at a single low rate, much like the U.S. does. In short, the phenomenon of capital being treated more gently than labor is widespread among rich nations. The United States is distinctive mostly in its lack of a VAT and its comparatively low corporate tax, but in terms of personal taxation the U.S. shares many features: flat payroll taxes, lower top marginal rates than many OECD peers, and special breaks for capital.

Canada and Australia offer illustrative contrasts in the Anglosphere. Canada’s top combined income rate (federal + provincial) can exceed 50%, higher than the U.S. However, until 2024 Canada also taxed capital gains very favorably: only 50% of a gain was included in income (rising to 66.7% after 2024), effectively giving a tax discount on gains. One report in 2022 called Canada’s tax changes “more regressive,” noting that policy shifts slightly raised taxes on the poor while cutting them for the wealthy. Australia likewise taxes capital gains only when realized and allows a 50% discount for assets held over a year. A recent analysis by the Australia Institute revealed that in 2023–24 Australian households had $1.39 trillion in capital gains versus $1.25 trillion in wages paid – yet almost none of those gains were taxed immediately. The wealthiest 10% of Australians received 80% of capital gains (and 80% of the $19 billion in CGT concessions). These examples underscore that many countries allow the rich to reap large untaxed or lightly taxed gains on assets, much as in the U.S.

Even Nordic countries – often seen as tax-equalizing models – have capital preferences. For example, while Norway has high income taxes (47% top federal) and taxes wealth modestly, its capital gains and dividends also enjoy lower rates. In sum, no major economy fully equalizes the tax burden on labor and capital. The U.S. stands out mainly for not offsetting its regressivity with generous social benefits; many Europeans pay slightly higher payroll/income taxes but receive more services in return. But in terms of rate structure, the U.S. approach is sadly common: flat taxes on consumption and payroll, plus preferential treatment for investment income.

Historical Anecdote: Tax Rules Shape Inequality

The long-term data are clear: when policymakers reduced high tax rates on the rich, inequality widened. From 1950 through the late 1960s, the U.S. economy grew rapidly while the top income tax rate was extremely high (up to 91%). Wealth concentration fell by mid-century. Then, starting in the 1960s and especially the Reagan era, the top tax rate plunged (to 50%, then 39.6%) and high earners found loopholes. Over the next decades, the share of income and wealth held by the very richest Americans soared.

Recent decades saw new examples of this dynamic. In 2017 Congress passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which cut the corporate tax rate and kept the top individual rate at 37% (with other changes). It also introduced a 20% deduction for pass-through business income, disproportionately benefiting high earners. Meanwhile, the capital gains tax rate stayed at 15–20%. Critically, the TCJA put a cap on the SALT deduction, which hurt wealthy taxpayers in high-tax states (like New York) but left in place the bigger tax advantages for capital. Left unaddressed were strategies like borrowing against stock portfolios (tax-free wealth extraction) and “buy, borrow, die” techniques for billionaires.

While many Americans feel shortchanged, policymakers have often defended the system. Some argue that lower tax rates on investment spur economic growth. But studies from the 1980s to today find little evidence that stock market activity slows when capital tax rates rise. Warren Buffett commented that even when capital gains rates were 39.9% in 1976–77, investment did not retreat. The overwhelming consensus among tax economists is that the preferences for capital chiefly serve to increase inequality, not to fund innovation or jobs.

As one OECD guide bluntly put it: “The favorable tax treatment of gains is a significant driver of low effective tax rates among high-net-worth individuals”. In 2024, President Biden and Democratic lawmakers proposed a “Billionaire Income Tax” on unrealized gains and higher top rates – but political hurdles remain. Until major changes occur, the tax code’s design continues to deepen the divide between labor and wealth.

Stories of Real People, Unfair Systems

The theory above plays out in real stories. Meet Linda, a single mom and retail worker making $30,000 a year. She sees nearly 7.65% of every paycheck vanish in Social Security/Medicare tax. Federal income tax might be another 10% of her income after credits. In stores, she pays 6–8% sales tax on clothes and food. Altogether, Linda regularly parts with a quarter of her earnings in tax. She has no stocks or rental properties, so none of her income can take advantage of low capital gains rates or retirement-deferred tax shelters. By contrast, her neighbor Robert is an entrepreneur whose wealth is tied up in a family business. He pays himself modest wages (up to the FICA cap) and takes profits via dividends and retained earnings. His capital gains tax rate is 15%, and by keeping profits in the company he defers tax indefinitely. In one recent year, Robert paid far less in income tax than Linda did – even though his wealth is much greater.

In the news: A 2020 exposé revealed that hedge fund manager Louis Bacon paid effectively 0% federal income tax for 2014–2018, despite earning hundreds of millions in profit. He did this using donations (to charity and politics) and business losses. Meanwhile, a school teacher or police officer typically pays at least 10–15%. Another case: Sam the Middle Manager made $200,000 in salary and $200,000 in stock gains. He owed $40,000 in income tax on the salary (20%) but only about $30,000 on the gains (15%). Adjusted for all payroll and itemized deductions, his overall effective rate was far lower than if all $400k had been ordinary wages.

And third example: rural Mississippi farmer Janet and her brother own a family farm worth $5 million. They improved land and sold some timber, but paid only capital gains tax on the profits at 0–15%. None of the increases due to land values (rising with development) will ever be taxed as long as they don’t sell. When Janet considered retiring, she learned that her heirs would inherit the farm free of any tax on its multi-million appreciation. Contrast that with Janet’s nephew who works in a diner: each dollar he earns is taxed immediately through payroll and income tax, and he can’t easily shield it.

These stories reflect a systemic pattern. In 2018 the Washington Post noted that billionaires have an effective tax rate lower than many teachers – a finding corroborated by leaked IRS data. In its analysis, Trump’s own taxes for years showed he paid almost nothing despite a massive fortune, while ordinary New Yorkers average about $7,000 in federal tax each year. In short, many everyday Americans feel the squeeze of paying taxes on every paycheck or purchase, even as the wealthiest deploy accountants and loopholes to diminish their bills.

The Case for Reform (and the Roadblocks)

The evidence is unambiguous: the poor and middle class carry a heavier tax load, proportionally, than the rich. That is true at the federal level (when all income is counted), and even more so at state and local levels. Anyone earning wages must pay payroll taxes on the first dollar, sales taxes on every purchase, and can rarely evade the standard income tax withholding system. By contrast, ultra-high earners can earn in ways that minimize or defer those taxes – and pass on wealth without ever paying tax on it.

Economists warn that this disparity worsens inequality. Wealth grows unchecked at the top when it is untaxed. A 2021 OECD guide recommended strengthening taxes on capital to improve fairness and efficiency. Some policy proposals – from wealth taxes to eliminating stepped-up basis to raising capital gains rates – aim to rebalance things. Indeed, only a few countries still lack any VAT or wealth tax, and no OECD country taxes all income (wealth or work) the same way.

However, major reforms face political headwinds. Many lawmakers claim higher taxes on the rich would hurt growth, even though historical evidence (and Buffett’s experience) suggests otherwise. Meanwhile, the wealthy have the resources to lobby or litigate for favorable rules. As a result, the U.S. tax system retains many privileged breaks for capital.

For working Americans, the result is grinding frustration. They see their paychecks shrink with each of the many taxes, and they seldom see a reduction in their effective tax rate as they earn more (after a point, federal rates flatten for middle incomes). But across town, a tech billionaire’s ballooning stock options may never trigger a tax bill. This deep unfairness – workers paying a hefty share of wages while billionaires skirt taxes on their tens of billions – is now widely acknowledged as a driver of the country’s inequality.

In the end, the question of “fair share” comes down to tax policy choices. The United States could restructure its code (for example, by taxing capital gains like wages, or by taxing the wealth itself), but to date it has generally not done so. Instead, the U.S. relies on a patchwork of wage taxes and relatively low taxes on wealth. Unless fundamental changes occur, that patchwork will continue to extract a larger bite from the many working Americans and a much smaller bite from the few at the top.