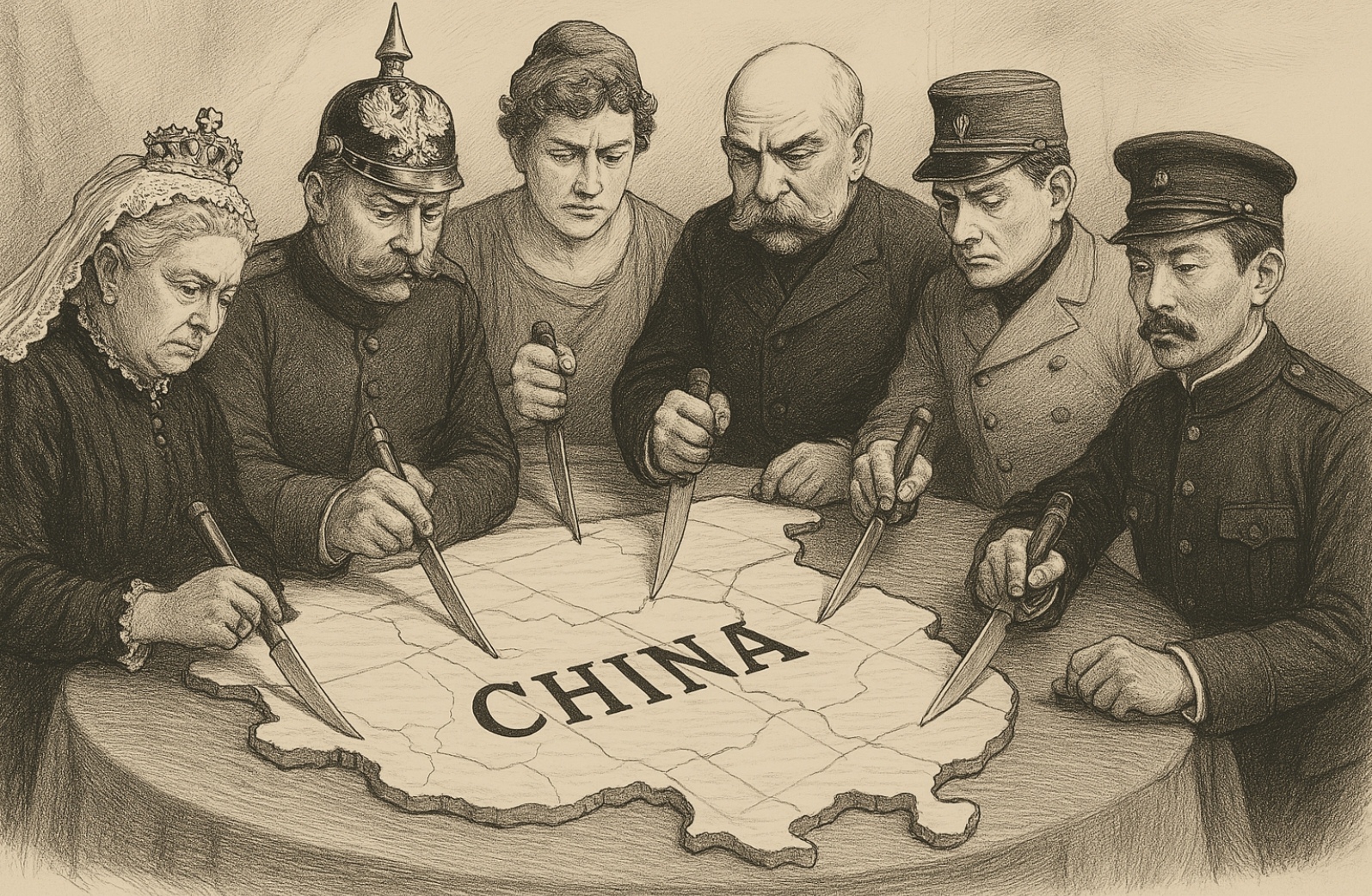

The Eight-Nation Alliance’s intervention in China during the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901) is often framed as a response to anti-foreign violence, but its deeper motivations were economic. The coalition—comprising Britain, France, Germany, Russia, the United States, Japan, Italy, and Austria-Hungary—was driven by the pursuit of trade dominance, territorial control, and financial interests.

By the late 19th century, China had become a battleground for foreign economic exploitation following a series of humiliating defeats in the Opium Wars (1839–1842, 1856–1860) and the imposition of unequal treaties. These agreements forced China to cede Hong Kong, open treaty ports to foreign merchants, and grant extraterritorial rights to Western and Japanese traders. Britain and France had already carved out significant spheres of influence in southern China, while Germany, Russia, and Japan competed for control over northern regions, particularly Manchuria and the Shandong Peninsula. The United States, although lacking territorial ambitions, pushed for the Open Door Policy to ensure equal trading rights in China, fearing that exclusive European and Japanese control would cut off American access to the vast Chinese market.

By the 1890s, Western and Japanese economic interests in China extended beyond trade into mining, railway construction, and banking, with foreign investments deeply embedded in the country’s infrastructure. As foreign concessions grew, resentment among Chinese citizens intensified, culminating in the Boxer Uprising—a nationalist and anti-foreign movement that sought to expel foreign powers and resist economic exploitation. The Eight-Nation Alliance’s military response to the uprising was justified as a mission to protect their nationals, but its true objectives included securing foreign financial interests, safeguarding trade routes, and reinforcing colonial dominance.

This article explores the economic underpinnings of the intervention, examining how capitalist elites influenced military actions and how economic competition among imperialist powers shaped their policies in China. The consequences of this intervention not only deepened foreign control over China’s economy but also set the stage for the country’s long struggle toward economic sovereignty and modernization.

Economic Conditions Leading to the Intervention

By the late 19th century, China was economically weakened and politically fragmented, making it a prime target for foreign exploitation. The Qing Dynasty, struggling with internal strife, corruption, and inefficiency, found it increasingly difficult to control its vast territory. Several key factors contributed to foreign intervention:

- Unequal Treaties and Economic Concessions: Following the Opium Wars, China was forced into a series of Unequal Treaties with Western powers and Japan. These treaties granted foreign nations control over key trade ports, such as Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Tianjin, which were vital centers for trade and commerce. Additionally, foreign powers were given tariff exemptions, meaning they were able to import goods into China without paying the high customs duties that were imposed on Chinese goods. Foreigners were also granted extraterritorial rights, which allowed them to live and operate outside Chinese law in designated areas known as concessions. This imbalance of power led to significant resentment among the Chinese population, who saw these treaties as humiliating and detrimental to national sovereignty.

- The Scramble for Markets: The period of rapid industrialization in Europe, Japan, and the United States created an insatiable demand for raw materials and new markets. As Western economies sought to expand their manufacturing capabilities, they turned to China, a country rich in natural resources, including silk, tea, porcelain, and minerals. In exchange for Chinese raw materials, foreign countries offered manufactured goods, which further cemented the trade imbalance in favor of Western powers. The growing global competition for markets during the late 19th century, often referred to as the “Scramble for Markets,” intensified this exploitation. Foreign powers were eager to secure China’s vast consumer base and extract resources such as coal, copper, and iron, which were crucial for their industrial operations.

- Financial Interests: Foreign banks and multinational corporations played an increasingly influential role in China’s economic landscape during the late 19th century. They heavily invested in infrastructure projects, particularly in the building of railroads, mining operations, and telecommunications networks. These investments were critical in opening up the interior of China for further exploitation and facilitating the extraction of raw materials to feed Western industries. The construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway by Russia and the Kwantung Railway by Japan, for example, linked remote regions of China to the broader global economy. These investments, however, were threatened by the rising tide of anti-foreign sentiment, which culminated in the Boxer Rebellion. As the Boxer movement gained momentum, the safety of foreign nationals and the protection of their investments became primary concerns for the imperial powers, spurring the formation of the Eight-Nation Alliance.

The Economic Interests of the Eight-Nation Alliance

Each member of the Eight-Nation Alliance had distinct economic objectives in China, driven by both national ambitions and the pressures of global capitalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Despite their differing goals, all the powers sought to maintain and expand their economic dominance through trade monopolies, resource extraction, and territorial concessions. Understanding these interests is crucial to comprehending the full scope of the Eight-Nation Alliance’s intervention in China during the Boxer Rebellion.

Western Powers: Protecting Trade Monopolies

Western powers, particularly Britain, France, and Germany, were deeply entrenched in China’s economic system by the late 19th century, having already secured favorable treaties that granted them significant privileges in the country. For these powers, the primary motivation behind their involvement in the Boxer Rebellion was to protect and expand their economic interests, as well as to safeguard their existing monopolies in trade, finance, and industry.

Britain: The Dominant Foreign Power in China

By the late 19th century, Britain was the most dominant foreign power in China, with a long history of economic exploitation through trade. Britain had established its economic foothold in China during the 19th century through the opium trade, which proved to be immensely profitable. Despite the official cessation of the opium trade following the Second Opium War (1856–1860), the British continued to profit from trade in other goods, such as tea, silk, and cotton. Key ports like Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Canton served as vital centers of British commercial activity.

Britain’s economic interests in China were multifaceted. The British government and business elites had significant investments in Chinese infrastructure, including railways, factories, and mines, which were critical for the extraction of raw materials and the export of goods back to Britain. British financiers also controlled major shipping lines and monopolies in various sectors, including cotton and silk industries. Furthermore, British merchants were highly involved in banking and the financing of international trade. The control of Shanghai as a major financial hub and the establishment of the International Settlement further cemented Britain’s economic dominance in the region.

British elites feared that the growing anti-foreign sentiment, exemplified by movements like the Boxer Rebellion, would threaten their economic interests, and were therefore committed to intervening militarily to preserve their commercial privileges. The British also sought to secure continued access to Chinese markets for their manufactured goods, as industrialization in Britain created a growing demand for international markets. Any disruption of their economic monopoly in China would have been detrimental to their global economic influence, and so they were determined to maintain their commercial advantages through military and diplomatic means.

France: Expanding Colonial Influence

France, like Britain, had established its economic foothold in China through a combination of trade, territorial control, and missionary work. French economic interests in China were focused primarily on infrastructure development, including the construction of railways, and access to natural resources. The French government and business elites were particularly interested in exploiting China’s rich mineral resources, including coal, iron, and copper, which were crucial for their expanding industrial economy.

French interests in China were also closely tied to their broader colonial ambitions in Asia, especially in Indochina. As part of their desire to expand French influence in the region, French business interests sought to build a network of railways that would connect French-controlled Vietnam with southern China, facilitating the flow of resources between the two regions. These railway projects were seen as key to enhancing France’s ability to access China’s rich agricultural and mineral wealth.

In addition to commercial and industrial ambitions, France’s involvement in China was also driven by its missionary activities. Catholic missionaries, supported by the French government, sought to expand their influence in China and convert the population to Christianity. The Boxer Rebellion, which targeted foreign missionaries and their Chinese converts, posed a direct threat to France’s religious interests in China, further motivating France to join the Eight-Nation Alliance in quelling the uprising. The protection of French citizens, including missionaries, was deemed essential to maintaining both economic and religious influence in the region.

Germany: Seeking Expansion in the Chinese Market

Germany, a relatively new imperial power in the late 19th century, was eager to establish itself as a dominant player in East Asia. German economic interests in China centered on expanding trade and securing access to the growing Chinese market for its industrial products, particularly steel, chemicals, and industrial machinery. Germany’s ambitions in China were also motivated by the desire to compete with other European powers, particularly Britain and France, in securing territorial concessions and exclusive economic privileges.

One of the most significant moves in Germany’s imperialist expansion in China was the seizure of Jiaozhou Bay in 1898, which was leased to Germany for 99 years. This strategic port on the Shandong Peninsula became a key base for German trade and military operations in the region. The establishment of a German protectorate over Jiaozhou Bay allowed German businesses to set up industrial operations and exploit China’s resources, including coal and iron. The port served as a gateway for German exports to China, further integrating the two economies.

Germany’s involvement in the Boxer Rebellion was partially driven by its desire to protect these newly established economic interests. The growing unrest in China, particularly the violence against foreign nationals and the threats to German-owned businesses, made it imperative for Germany to intervene. By joining the Eight-Nation Alliance, Germany aimed to safeguard its colonial investments and ensure continued access to the Chinese market for its industrial products. The Boxer Rebellion, in this context, was seen as an opportunity for Germany to assert its dominance in China and solidify its economic and geopolitical position in East Asia.

Overall, while each member of the Eight-Nation Alliance had distinct economic objectives, they all shared a common desire to protect and expand their commercial interests in China. Through military intervention, they sought to preserve their trade monopolies, safeguard their financial investments, and maintain exclusive access to China’s vast resources and markets. These economic motivations were at the core of their collective action during the Boxer Rebellion, and they shaped the economic trajectory of China for decades to come.

Russia and Japan: Expansionist Economic Goals

- Russia: The Russian Empire was particularly interested in expanding its influence in Manchuria, a resource-rich region in northeastern China. The acquisition of control over Manchuria and its vital resources, including coal, timber, and agricultural land, was seen as essential to Russia’s economic and strategic interests. In 1896, Russia secured a lease from China for the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER), which would link Russia’s Siberian Railway to the Chinese port of Dalian, providing Russia with direct access to the Pacific Ocean. This railway became a key component of Russia’s broader plan to assert dominance over Manchuria and its resources, and it played a crucial role in facilitating the transport of Russian goods and military personnel to and from the region.

- Russia’s imperial ambitions in China were also fueled by its desire to prevent Japan from gaining too much influence in the region. The Russian Empire had long viewed Manchuria and Korea as critical to its geopolitical security, and Russian leadership saw Japan’s rapid modernization and imperial expansion as a direct challenge to its interests. Russia feared that if Japan gained control of Manchuria or Korea, it would shift the balance of power in East Asia and diminish Russia’s ability to expand westward. The Boxer Rebellion gave Russia a pretext to send military forces into China to secure its economic investments, particularly the CER, and to safeguard its ambitions in Manchuria.

- Japan: Following the Meiji Restoration (1868), Japan rapidly modernized and industrialized, transforming itself into a formidable military and economic power. Japan sought to expand its influence across East Asia, especially in Korea and northern China, regions rich in raw materials and strategically important for Japan’s growing industrial economy. Japan’s interest in Korea was primarily driven by the desire to access its agricultural resources and mineral wealth, while its interest in northern China, including Manchuria, was motivated by the potential to secure valuable raw materials such as coal, iron, and soybeans.

- Japan’s expansionist goals were formalized through the acquisition of territories and economic zones. In 1895, after its victory in the First Sino-Japanese War, Japan annexed Taiwan and gained significant control over Korea. This set the stage for Japan’s more aggressive actions in China during the Boxer Rebellion. Japan, which had secured significant commercial and territorial privileges in China through unequal treaties, was eager to protect and expand these holdings. Japan’s economic interests were also closely tied to its military activities, as it sought to secure ports, railway networks, and mining concessions to ensure the flow of resources necessary to sustain its rapidly growing economy. Japan’s intervention in the Boxer Rebellion was motivated not only by the desire to protect its economic investments but also by its ambition to establish itself as the dominant power in East Asia.

The United States: An Open Door Policy for Economic Gain

Unlike European powers that favored direct territorial control over their spheres of influence, the United States pursued a different approach in China, known as the Open Door Policy. The policy, first articulated in 1899 by U.S. Secretary of State John Hay, advocated for equal trading rights for all nations within China, with the goal of ensuring that no single power would dominate Chinese markets. While the United States did not seek formal colonization, American businesses and financiers had substantial interests in protecting their investments in the Chinese economy.

The Open Door Policy was motivated by the need to secure unfettered access to Chinese markets, which were seen as vital to the U.S. economy. By the turn of the 20th century, American businesses had already invested heavily in China, particularly in railroads, mining, and the burgeoning consumer market. American entrepreneurs, including those in the railroad industry, were eager to expand their operations in China, seeing the country as a potential market for agricultural goods, machinery, and manufactured products. The U.S. also had a vested interest in securing favorable terms for its merchants and financiers in Chinese ports, which were increasingly controlled by European and Japanese powers.

Despite advocating for an “Open Door” policy, the United States’ economic interests were deeply tied to securing exclusive access to Chinese markets. While the U.S. did not seek territorial control, it wanted to ensure that American businesses could compete on an equal footing with European and Japanese companies. As part of this strategy, the U.S. government engaged in diplomatic efforts to preserve the balance of power in China, ensuring that no single nation could monopolize trade or extract too much influence from the country. The U.S. intervention in the Boxer Rebellion, while framed as a defense of Chinese sovereignty, was also intended to protect American economic interests in the region and ensure continued access to the vast Chinese market.

In addition to economic interests, the United States saw its involvement in China as part of a broader strategy to secure its position as a global power. The intervention in the Boxer Rebellion reinforced the idea of the U.S. as a rising imperial power, committed to defending its commercial interests and ensuring its access to key international markets.

The Role of Industrial and Financial Elites

Economic elites played a crucial role in shaping the foreign policy decisions of the Eight-Nation Alliance during the Boxer Rebellion and in the years that followed. These elites were primarily motivated by financial interests and a desire to expand their power, which they achieved through military interventions, infrastructure development, and financial control. Their influence significantly shaped the dynamics of imperialism in China and the broader global economic system.

- Arms and Infrastructure Industries: Western arms manufacturers were key beneficiaries of the military interventions during the Boxer Rebellion. These companies, including giants like Krupp (Germany) and Vickers (Britain), were able to profit immensely from supplying both their own governments and factions within China with weapons and military equipment. The demand for arms fueled further instability in the region, as the various factions—both foreign and domestic—competed for control. This created a cycle where foreign powers continuously intervened in China, maintaining instability in the country and ensuring ongoing profits for military suppliers. The Chinese conflict was not only a political and military battle but also a lucrative market for arms companies, whose economic power influenced foreign policy decisions in favor of prolonged interventions.

- Banking Sector: The involvement of European and American banks in China was also central to the financial exploitation of the country. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, banks such as the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) and the Deutsche Bank extended loans to Chinese provincial governments. These loans, often secured with land or resources, forced the Qing Dynasty into an economic dependency on foreign credit, deepening China’s vulnerability to foreign influence. As a result, the Chinese government was unable to finance much-needed reforms without incurring substantial debt to foreign banks. This created an economic environment where China’s fiscal policies were heavily influenced by foreign interests, and its sovereignty was further compromised. The legacy of foreign-controlled banking in China laid the groundwork for further exploitation by international financiers and gave foreign powers leverage in their dealings with the Qing government.

- Colonial Business Interests: Several multinational corporations had significant financial stakes in maintaining China’s economic subjugation. Companies such as the British East India Company, which had previously played a central role in controlling opium trade in China, and German industrial firms, which invested heavily in the construction of railroads and other infrastructure, were among the most powerful actors in the region. These companies were incentivized to protect their financial interests in China, which included profitable trade agreements, concessions, and control of resources. The economic influence of such businesses ensured that foreign powers had the ability to dictate the economic direction of China for decades. American trade consortia also played a major role in securing access to China’s vast markets, and their lobbying efforts within the U.S. government were key in shaping U.S. foreign policy. These business interests helped ensure the persistence of an unequal global economic system, wherein imperial powers maintained economic control over China’s vast resources and strategic markets.

The Economic Consequences of the Intervention

The suppression of the Boxer Rebellion and the subsequent foreign intervention had far-reaching economic consequences for China. The effects of these interventions were felt throughout the early 20th century, as foreign powers solidified their control over China’s economy and exploited its resources. This period marked a critical phase in China’s struggle for sovereignty, and the economic consequences laid the groundwork for both resistance movements and long-term instability.

- Increased Foreign Economic Control: One of the most significant economic consequences of the Boxer Rebellion was the imposition of the Boxer Protocol in 1901, which forced China to pay massive indemnities to the foreign powers involved in the intervention. The Qing government was required to pay 450 million taels of silver (equivalent to approximately $330 million at the time), a sum that placed enormous financial strain on the already weakened Chinese state. The indemnities were paid over a period of several decades, further indebting the Qing government and perpetuating China’s economic dependence on foreign powers. This financial burden made it difficult for China to implement reforms or invest in modern infrastructure, contributing to its continued vulnerability to external pressures. The indemnities also had long-term economic consequences, as the funds were used to support foreign businesses, military operations, and diplomatic influence rather than improving China’s own development.

- Strengthening of Spheres of Influence: In addition to the financial indemnities, the foreign powers involved in the intervention further entrenched their economic dominance by expanding their spheres of influence within China. Through a series of treaties, foreign nations obtained exclusive rights to control key industries, ports, and trade routes. Britain, Germany, Russia, Japan, and other powers gained control over lucrative trade ports such as Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Tianjin, establishing economic enclaves where they exercised authority over local governance and commerce. These spheres of influence allowed foreign companies to operate without interference from the Chinese government, ensuring that they could extract maximum profits from Chinese resources. Foreign-owned railroads, mining operations, and shipping lines further integrated China into the global capitalist system, but this came at the expense of China’s economic independence and sovereignty.

- The Rise of Chinese Nationalism: The economic exploitation of China during the Boxer Rebellion and the subsequent foreign interventions fueled growing resentment among Chinese intellectuals and reformers. The mounting financial burdens and increasing foreign control over China’s economy sparked nationalist movements that sought to restore China’s sovereignty and break free from the grip of foreign imperialism. Figures such as Sun Yat-sen, who would later lead the revolution that overthrew the Qing Dynasty, called for modernization and the establishment of a republican government that would be free from foreign influence. The humiliation of the Boxer Rebellion and the economic subjugation that followed also contributed to the decline of the Qing Dynasty, which was already weakened by internal corruption and external pressures. The economic consequences of foreign intervention played a central role in the eventual collapse of the Qing Dynasty and the rise of the Chinese Republic in 1912, marking a turning point in China’s history and its ongoing struggle for political and economic independence.

The Evolution of the Eight-Nation Alliance into the G7

While the Eight-Nation Alliance was initially formed to suppress the Boxer Rebellion, its member nations continued to shape global economic and geopolitical structures throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. The military intervention during the Boxer Rebellion was only one chapter in the broader narrative of imperialism, economic dominance, and international cooperation that defined these nations’ actions. Over time, the nations of the Eight-Nation Alliance—Britain, France, Germany, Russia, Japan, the United States, Italy, and Austria-Hungary (though Austria-Hungary no longer exists as a political entity)—evolved their economic and political relations, ultimately leading to the formation of the Group of Seven (G7), an influential forum for global economic governance. Today, the G7 includes the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan, and it serves as a platform for shaping global economic policy and addressing complex international challenges. This transition reflects a broader shift from imperialistic power struggles to more formalized, yet still unequal, systems of global governance.

Post-WWI and WWII Economic Collaboration

Following World War I and World War II, the industrial powers of the Eight-Nation Alliance were major players in shaping the new global economic order. The aftermath of the two world wars provided both challenges and opportunities for these nations, as they sought to rebuild their economies and prevent future conflicts. The devastation of war had highlighted the need for a more coordinated economic approach to promote international stability and prevent another global depression, which had contributed to the rise of fascism and global instability in the 1930s.

In response to the economic dislocations caused by the wars, the Allies—primarily the United States, Britain, and France—established key international institutions designed to stabilize the global economy. One of the most significant initiatives was the Bretton Woods Conference of 1944, which led to the creation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. These institutions were designed to promote international financial stability, support post-war reconstruction, and foster global economic growth. The IMF’s role in stabilizing national economies through currency exchange and balance of payments support became crucial in the decades following WWII, while the World Bank focused on funding development projects in newly independent nations and war-torn countries.

The Bretton Woods system also established the U.S. dollar as the world’s primary reserve currency, further consolidating the economic dominance of the United States, which had emerged from WWII as the world’s leading economic power. This system provided a framework for economic cooperation that was rooted in the interests of the major industrial powers of the Eight-Nation Alliance and established the foundation for the post-war economic order.

Cold War and Economic Coordination

With the onset of the Cold War in the late 1940s, global capitalism found itself in direct competition with the Soviet Union’s socialist economic model. The ideological and economic rivalry between the two superpowers—led by the United States and the Soviet Union—shaped the geopolitical landscape for much of the 20th century. In response to the threat posed by Soviet communism, the Western capitalist nations coordinated their economic policies and trade strategies in an effort to bolster the global capitalist system and maintain a competitive edge.

The G7, initially an informal forum of leading industrialized nations, was formally established in 1975 as a means of coordinating economic policies among the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Japan, and Italy. At its core, the G7 was driven by the need for the industrialized powers to present a unified front against the Soviet Union, which was seen as a direct threat to the capitalist global order. The group’s agenda focused on promoting economic stability, liberal trade policies, and managing global financial crises. While it was originally created as a forum for economic cooperation, the G7 quickly expanded its focus to include broader global issues such as security, environmental sustainability, and human rights, reflecting the changing geopolitical realities of the post-Cold War world.

Throughout the Cold War, the G7 members coordinated their economic and military strategies, facilitating the flow of trade, technology, and investment among themselves while excluding socialist and developing nations from the decision-making processes. This economic coordination was instrumental in promoting economic growth in the West, particularly in Europe and Japan, which had been devastated by the war but were rapidly recovering due to the support of American capital and investment. The success of the G7 in maintaining global capitalist stability during the Cold War era can be seen as a continuation of the imperial economic strategies that were first articulated by the Eight-Nation Alliance during the Boxer Rebellion. The Cold War-era economic policies of the G7 represented a formalization of the economic dominance of the industrial powers that had intervened in China during the Boxer Rebellion.

Modern Economic Governance

Today, the G7 remains a central institution in global economic governance, although its role has evolved in response to the changing dynamics of global politics and the rise of new economic powers. While the original G7 members continue to shape global economic policies, other nations—particularly China, India, and Brazil—have risen as significant players in the global economy. The G7, however, still represents a coalition of the world’s most advanced economies, accounting for a substantial portion of global GDP, international trade, and technological innovation.

The G7 serves as a platform for addressing a wide range of global economic challenges, including financial stability, trade policies, climate change, and technological advancement. In recent years, the group has taken on a more proactive role in addressing issues such as income inequality, global health crises (such as the COVID-19 pandemic), and environmental sustainability. While the G7’s economic policies still reflect the interests of its member nations, it has also had to confront the rising economic influence of countries like China, which continues to challenge the Western-dominated global economic order.

Despite its evolution into a more formalized platform for global governance, the G7 continues to reflect some of the same dynamics of economic control and influence that characterized the actions of the Eight-Nation Alliance. While the imperialist methods of direct territorial control have been replaced by more sophisticated economic tools—such as trade agreements, multinational corporations, and financial institutions—the G7 continues to be an important forum for shaping the rules of global capitalism. The lessons of the Eight-Nation Alliance, particularly the ways in which economic dominance can be achieved through military intervention, diplomatic pressure, and international institutions, remain relevant in understanding the ways in which the global economic system is structured today.

The Legacy of Economic Imperialism: How the Eight-Nation Alliance Shaped Modern China

The intervention of the Eight-Nation Alliance was not merely a reaction to the Boxer Rebellion but a calculated move to secure economic dominance in China. Capitalist interests shaped military strategies and diplomatic policies, ensuring that financial gain remained at the core of imperialist interventions. The long-term effects of these economic impositions contributed to China’s struggle for sovereignty and shaped its modern approach to economic and political independence.

As China emerged from the shadows of imperial exploitation, it adopted policies focused on economic self-sufficiency, industrial modernization, and strategic global positioning. The experience of foreign intervention fostered a deep mistrust of Western economic control, influencing China’s policies on foreign direct investment, trade agreements, and global financial institutions. Furthermore, China’s rise as an economic powerhouse in the 21st century can be seen as a direct response to its historical subjugation, with policies such as the Belt and Road Initiative aiming to reshape the global trade order on its own terms.

The legacy of the Eight-Nation Alliance is thus twofold: it not only contributed to China’s economic hardships but also set the foundation for its modern resurgence. As China continues to assert its influence on the global stage, the historical scars of economic imperialism remain a guiding force in its geopolitical and economic strategies.