The United States has amassed a record-high national debt, approaching roughly $35–36 trillion by early 2025. This debt is the sum of all outstanding U.S. Treasury securities – the bedrock instruments of global finance – and it is owed to a wide array of creditors. Broadly, America’s debt is held by domestic entities (including U.S. government accounts, the Federal Reserve, banks, mutual funds, pensions, and individuals) and foreign investors (ranging from foreign governments to international investors). This article provides a detailed breakdown of who owns U.S. government debt in 2024–2025, examines how this ownership has shifted over time, and discusses the implications of the current debt ownership structure.

Overview of U.S. Debt Composition (2024–2025)

As of late 2024, gross U.S. federal debt stands around $35.5 trillion. This can be divided into two main components:

- Debt Held by the Public (~$28–29 trillion): The portion of debt held by outside investors (domestic and foreign) and the Federal Reserve. These are marketable Treasury bills, notes, and bonds sold in financial markets (plus a small amount of non-marketable debt like savings bonds and certain state/local holdings).

- Intragovernmental Holdings (~$7 trillion): The portion of debt the government owes itself. This is held in federal government trust funds and accounts (for example, the Social Security Trust Fund, Medicare Trust Fund, and civil service retirement funds) as special Treasury securities.

In percentage terms, about 79–80% of the debt is held by the public and 20–21% is intragovernmental as of 2024. Intragovernmental debt represents internal accounting between government accounts and has no direct impact on credit markets (it’s essentially one arm of the government owing another). However, it reflects obligations to future program beneficiaries – for instance, the Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund holds about $2.6 trillion (roughly 38% of intragovernmental debt), which will be drawn down to pay retirees, converting that internal debt into public debt over time.

By contrast, the $28+ trillion in publicly held debt is what the government owes to outside creditors and is crucial for financial markets. Below, we break down the major holders of this publicly held debt, first looking at domestic holders and then foreign holders.

Major Domestic Holders of U.S. Debt

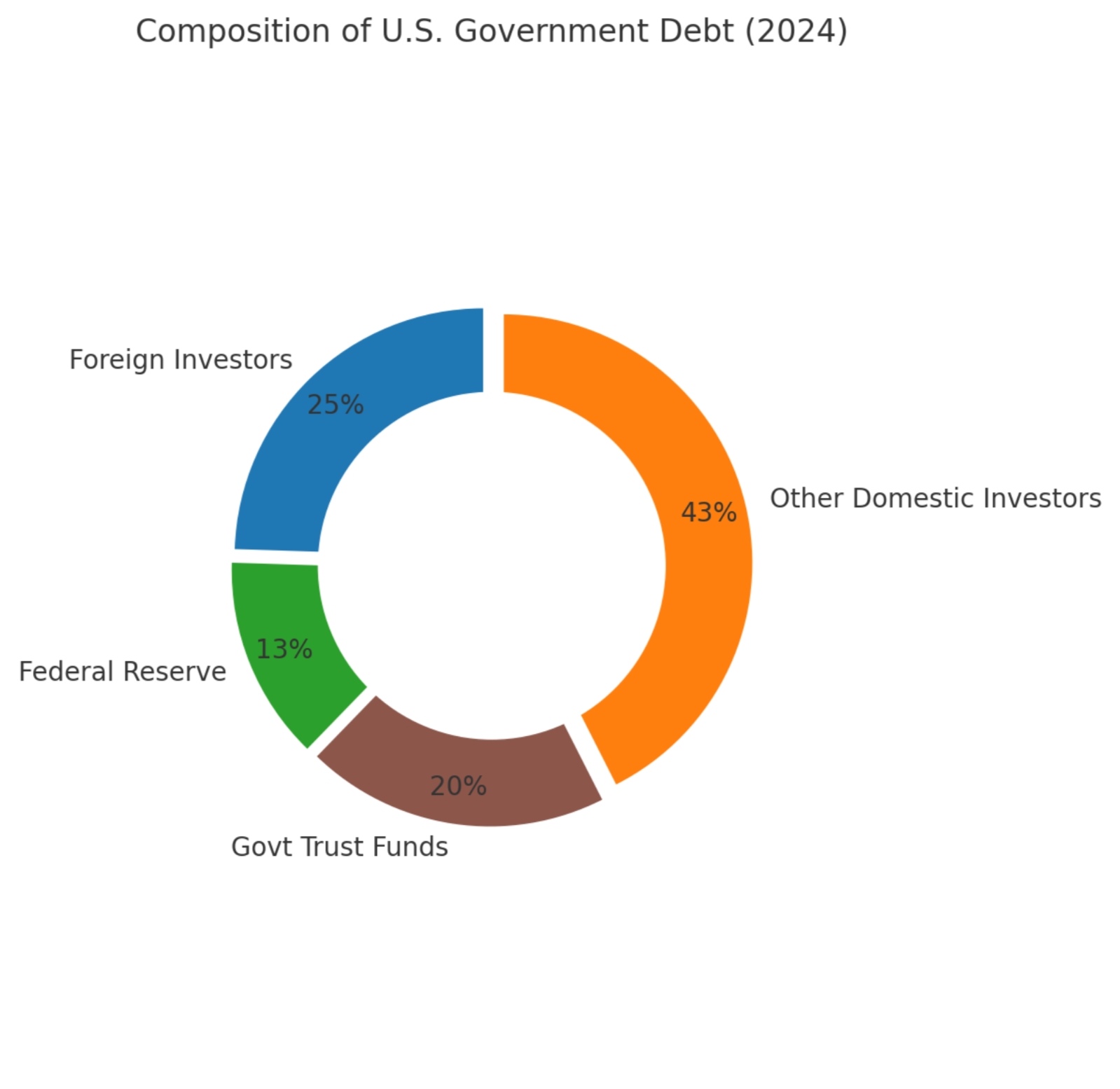

Composition of U.S. government debt by holder in 2024. “Other Domestic Investors” include U.S. mutual funds, banks, insurers, pensions, corporations, and individuals. Data based on U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve reports.

About three-quarters of U.S. public debt is held by domestic entities (the U.S. government itself, the Federal Reserve, and various U.S. investors). The remaining roughly one-quarter is held by foreign investors (detailed in the next section). The domestic holders of U.S. debt can be further categorized as follows:

- Federal Reserve: The U.S. Federal Reserve (the nation’s central bank) is the single largest holder of U.S. government debt. As of early 2025, the Fed holds around $4.7 trillion in Treasury securities – roughly 13% of total U.S. debt (or about one-third of all domestically held public debt). The Fed’s holdings ballooned in recent years due to quantitative easing (QE) programs: for example, it increased its Treasury holdings from about $1 trillion in 2010 to over $6 trillion at the peak of the pandemic response in 2022. Since 2022, the Fed has been gradually reducing its bond holdings (quantitative tightening) to combat inflation, bringing its share down slightly. Even so, the Federal Reserve’s portfolio of Treasuries remains enormous, making it a key lender to the U.S. government. (Notably, interest paid on Treasuries held by the Fed is mostly remitted back to the U.S. Treasury after the Fed covers its expenses, somewhat blunting the cost of that portion of the debt.)

- U.S. Government Accounts (Intragovernmental Holdings): Various federal government trust funds and accounts together hold roughly $7.0 trillion in Treasuries (about 20% of total debt). These are not investors in the usual sense – they reflect money the government owes to programs like Social Security, Medicare, and federal employee retirement funds. The largest such holder is the Social Security Trust Fund (OASI), with about $2.6 trillion in Treasuries. Other sizable intragovernmental holders include the Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) fund, the Medicare Hospital Insurance fund, and federal military/civil service retirement funds. While these accounts hold a significant share of the debt, this portion is essentially the government’s IOUs to itself. As these obligations come due (for example, paying Social Security benefits), the Treasury will need to finance them by issuing new debt to the public or raising revenues.

- Mutual Funds and Pension Funds: Investment funds are major purchasers of U.S. debt. U.S.-based mutual funds (including money market funds) alone hold on the order of several trillion dollars in Treasuries – roughly 10% of the total debt. At the end of 2023, mutual funds and similar investment vehicles held about $3.6–4.0 trillion in Treasuries (including short-term T-bills via money market funds). Pension funds also invest in Treasuries for safety and liquidity. Private pension funds held around $0.45 trillion as of 2023, and state/local government pension funds around $0.40 trillion. Together, mutual funds and pension funds account for a substantial share of domestic privately-held debt (roughly 12–15% of U.S. public debt).

- Banks and Financial Institutions: U.S. depository institutions (banks and credit unions) and other financial entities are significant holders of Treasury securities. At the end of 2023, U.S. depository institutions held roughly $1.6–1.7 trillion in Treasuries – about 5% of total U.S. debt. Banks hold Treasuries as part of their investment portfolios and to meet liquidity and regulatory requirements. Insurance companies, too, invest in Treasuries (around $0.4 trillion as of 2023) to match their long-term liabilities. Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and other financial firms also hold some U.S. debt (often included in “other investors” category).

- State and Local Governments: Besides their pension funds, state and local governments themselves sometimes hold Treasuries (for example, in rainy-day funds or other cash management accounts). Collectively, state and local governments held roughly $1.5–1.6 trillion in Treasuries as of 2023, about 4–5% of the total debt. These holdings are often short-term and for liquidity purposes.

- Households and Other Investors: The category of “other investors” includes U.S. individual investors, corporations, estates, trusts, and other entities not classified elsewhere. This group also holds a large chunk – on the order of $5–6 trillion – of the national debt (this can include wealthy individuals’ holdings, non-profit organizations, U.S. savings bonds held by households, etc.). For instance, Americans hold about $0.17 trillion in the form of savings bonds (non-marketable bonds popular with individuals). Many individuals also indirectly hold U.S. debt through bond funds, ETFs, or retirement accounts that are part of the above categories.

In sum, domestic holders – spanning the Federal Reserve, government accounts, and U.S. private investors – account for the majority (~75%) of America’s debt. Importantly, the Federal Reserve’s ownership plus intragovernmental holdings (together, roughly one-third of total debt) mean that a sizable portion of the debt is effectively owed “to ourselves” as a nation. The remaining portion (debt held by domestic private investors and foreign investors) is subject to market forces and investor sentiment. Next, we look at the foreign share of U.S. debt, which, while smaller than the domestic share, still represents trillions of dollars held by overseas creditors.

Foreign Holders of U.S. Debt

Foreign investors hold approximately $7–8.7 trillion of U.S. Treasury debt, making up roughly 24% of America’s total debt as of 2024. This includes both foreign governments (central banks) and private foreign investors. U.S. Treasury securities are attractive globally because they are considered one of the world’s safest assets – backed by the U.S. government’s full faith and credit. Many countries buy U.S. debt to store foreign exchange reserves or stabilize their currencies, and international investors buy Treasuries for safety and liquidity.

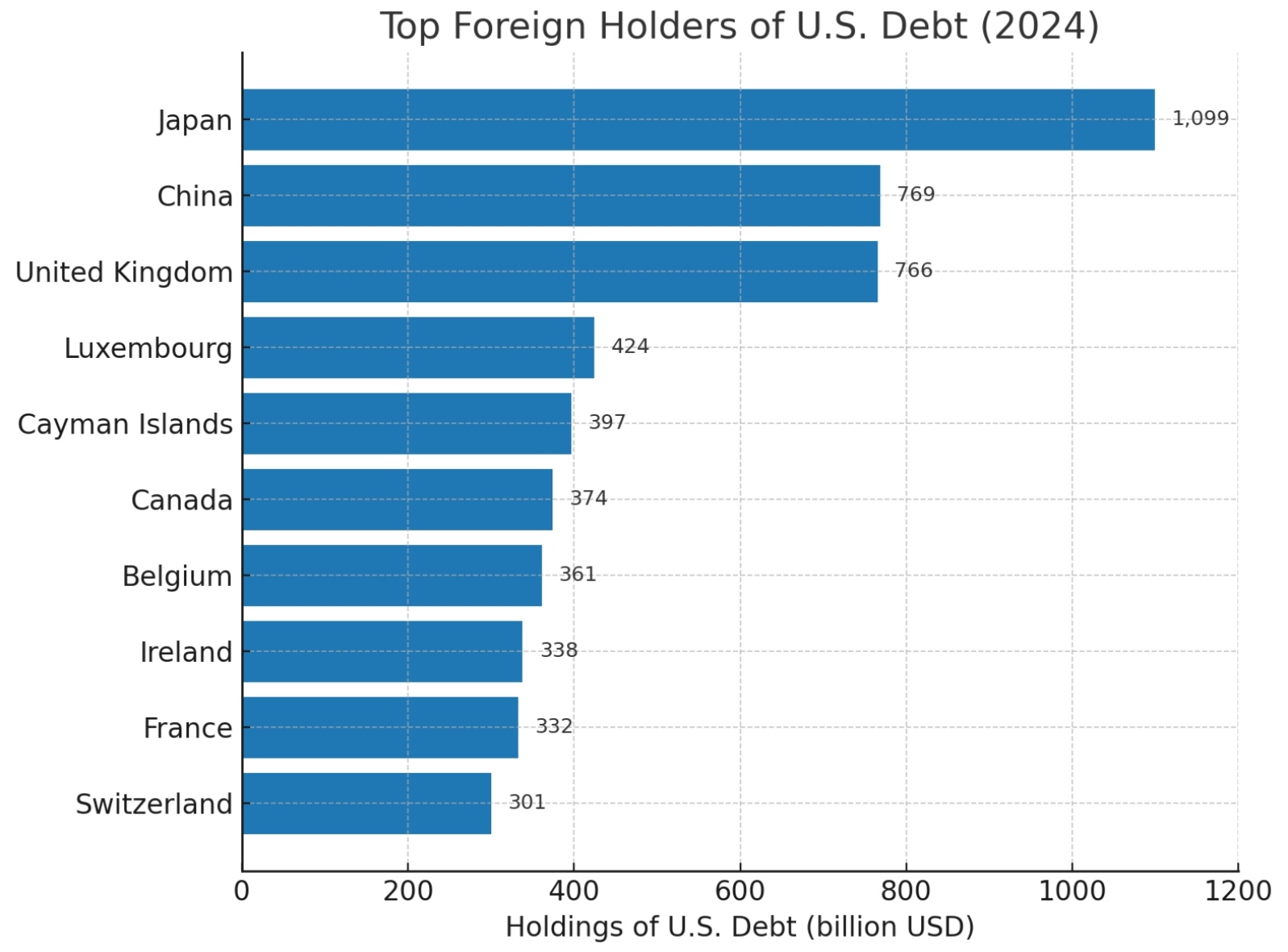

Top foreign holders of U.S. Treasury debt (in USD billions) as of end of 2024. Japan and China are the largest foreign creditors, collectively holding about 5% of total US debt. Data source: U.S. Treasury TIC report.

Japan and China are the two largest foreign holders of U.S. debt. As of late 2024, Japan holds about $1.09 trillion in U.S. Treasuries, and China holds about $0.77 trillion. Together, these two East Asian economic giants account for roughly one-quarter of all foreign-held U.S. debt. (A decade ago, China’s holdings were larger – peaking above $1.3 trillion around 2013 – but have since declined, while Japan’s holdings have remained relatively steady.) Both countries invest in U.S. bonds as a safe place to park their extensive foreign exchange reserves and to manage their currencies’ exchange rates.

Other major foreign holders include:

- United Kingdom – about $766 billion (the UK is a major financial center, and some of these holdings may be by UK-based custodians on behalf of other international investors).

- Luxembourg – around $425 billion (Luxembourg’s large total reflects its status as a financial hub where many investment funds operate).

- Cayman Islands – about $397 billion (another financial center; many hedge funds and custodial accounts for international investors are domiciled here).

- Canada – roughly $374 billion.

- Belgium – about $361 billion.

- Ireland – about $338 billion.

- France – about $333 billion.

- Switzerland – about $301 billion.

- Taiwan – about $287 billion.

- India – about $234 billion.

- Brazil – about $229 billion.

In addition, oil-exporting nations like Saudi Arabia ($128 billion), Mexico ($98 billion) hold notable amounts. The category “Rest of the World” (all other countries combined beyond the top holders) accounts for roughly $1.59 trillion. This long tail includes numerous countries each holding tens of billions in U.S. debt.

It’s important to note that the U.S. Treasury’s country-by-country figures are based on where securities are held in custody, which can obscure the ultimate ownership. For example, Chinese investors might purchase Treasuries through accounts in Belgium or London. Nevertheless, the data gives a good approximation of the major foreign creditors.

Overall, foreign entities hold about 24% of U.S. public debt in 2024, down from roughly 34% a decade earlier. In 2014, foreign holdings peaked at ~33.9% of total debt (around $8.0 trillion at the time, on a smaller debt base). Over the past decade, the U.S. debt has grown rapidly, and domestic buyers (especially the Fed and U.S. institutions) absorbed much of the increase, causing the foreign share to fall. Foreign governments like Russia have also sharply reduced their U.S. debt holdings in recent years (Russia sold off most U.S. bonds amid sanctions and geopolitical tensions).

Despite the declining share, foreign investors remain absolutely crucial. The doubling of foreign-held U.S. debt from about $4 trillion in 2010 to over $8 trillion in 2024 has provided the U.S. government with ample financing. Global demand for dollars and Treasuries allows the U.S. to run budget deficits more easily, but it also means a significant portion of U.S. interest payments flows abroad to these creditors.

Historical Shifts in Debt Ownership

The ownership landscape of U.S. debt has shifted significantly over time:

- Rise (and Fall) of Foreign Share: Fifty years ago, foreign holdings of U.S. debt were negligible – only about 5% in 1970. The share of debt held by foreign investors climbed dramatically in the 1990s and 2000s, reaching a peak of about 49% of publicly held debt in 2011. This was fueled by globalization, trade imbalances (countries like China accumulating dollars and reinvesting them in Treasuries), and oil exporters recycling petrodollars. However, since 2011 the foreign share has declined to roughly 24–30% by 2023–2024. The decline in percentage is partly because domestic holdings (especially by the Fed) grew rapidly in response to crises. In absolute terms, foreign holdings are near all-time highs (~$8 trillion), but domestic holdings grew even faster in the past decade. Notably, China’s holdings have decreased over the past decade (from over $1.2T in 2010 down to ~$770B now) due to financial strategy changes and capital outflows, whereas Japan’s holdings have remained large and stable, recently overtaking China as the top foreign creditor.

- Federal Reserve’s Expansion: Historically, the Federal Reserve held a relatively small portion of the national debt (mainly as needed for monetary policy). In 2007 (pre-financial crisis), the Fed held around $0.8 trillion of Treasuries. This changed with the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, when the Fed engaged in massive bond-buying (QE) to lower interest rates and support the economy. The Fed’s Treasury holdings jumped from ~$1 trillion in 2010 to over $4.5 trillion by 2014, then to $6+ trillion in 2020–2021. As of 2024, the Fed’s share is receding slightly due to policy normalization, but it remains the largest single domestic holder of U.S. debt – a dramatic shift from two decades ago when foreign investors or U.S. mutual funds were larger holders than the Fed.

- Intragovernmental vs Public Debt: In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Social Security trust fund was running surpluses and accumulating Treasuries, which swelled intragovernmental debt. By 2008, intragovernmental holdings were about 45% of gross debt. Since then, however, debt held by the public has grown much faster than intragovernmental debt, due to large budget deficits and the eventual shift of Social Security to cash deficits. Today, intragovernmental debt is only ~20% of gross debt. The Social Security trust fund is projected to be drawn down in coming years (as retiree benefits exceed payroll tax revenues), which will further reduce intragovernmental holdings and require more borrowing from the public.

- Domestic Private Investors: U.S. banks, funds, and individuals have always been key lenders to the government, but their role has grown as the debt has exploded. For instance, U.S. private sector holdings grew from about $8 trillion in 2010 to nearly $24 trillion in 2024. Mutual fund ownership of Treasuries surged with the growth of money market funds and bond funds. The composition of domestic private holders has evolved – e.g., banks increased holdings post-2008 due to new liquidity rules (and then slightly reduced them when yields rose sharply in 2022–2023), and money market funds became dominant players in T-bill markets especially in times of financial uncertainty (like during COVID-19, when they absorbed much of the surge in short-term Treasury issuance).

These shifts underscore that who finances U.S. debt can change depending on economic conditions, policies, and global trends. After 2008 and 2020, the Federal Reserve stepped in as a buyer of last resort. Meanwhile, foreign central banks like China’s reduced their reliance on Treasuries, while domestic investors took up more. The landscape continues to evolve with each economic cycle and policy change.

Implications and Risks of the Current Debt Ownership Structure

The structure of U.S. debt ownership in 2024–2025 carries several implications and potential risks for the economy and national security:

- Foreign Influence & Economic Diplomacy: With roughly a quarter of U.S. debt held abroad, the U.S. is somewhat reliant on foreign creditors. This raises concerns (often debated in policy circles) about potential foreign leverage over the U.S. For example, could a major holder like China destabilize U.S. finances by suddenly selling its Treasury holdings? In practice, dumping Treasuries would also hurt the seller (by driving down bond prices), and there are limited alternative safe assets for countries to invest in at this scale. Nonetheless, the U.S. must consider that foreign governments manage their Treasury holdings in line with their own interests, and geopolitical tensions could influence their behavior. A gradual decline or slower growth in foreign demand (already observed in recent years) means the U.S. Treasury may need to rely more on domestic buyers, which could push interest rates higher if not enough buyers are found.

- Interest Payments Flowing Overseas: When foreign investors hold U.S. debt, interest payments on those bonds send income abroad. As of FY2024, U.S. annual gross interest outlays exceeded $1 trillion for the first time, and a portion of that – perhaps around $250 billion – is paid to foreign holders. This is income not retained in the domestic economy. Over time, large external debt means a transfer of wealth abroad in the form of interest, which can modestly dampen U.S. national income relative to a scenario where all debt was domestically held.

- Crowding Out and Financial Stability: Heavy reliance on domestic investors to absorb debt can crowd out private investment – i.e. if banks, funds, and others put more money into Treasuries, that’s less available for lending to businesses or investing in corporate bonds/stocks. On the other hand, high domestic ownership also indicates strong internal capacity to finance deficits. The mix of domestic holders matters for financial stability. For instance, banks holding large amounts of Treasuries face interest rate risk – as seen in 2022–2023, when rising interest rates caused unrealized losses on banks’ bond portfolios (a factor in some regional bank failures). Similarly, the substantial Fed ownership of Treasuries concentrates a lot of bonds in one entity; as the Fed unwinds its holdings, the private market must absorb more supply, which could put upward pressure on interest rates.

- Monetary Policy and Federal Reserve Holdings: The Fed’s large Treasury holdings tie into monetary policy. By holding so much government debt, the Fed has kept borrowing costs lower than they might otherwise have been. As it sells or lets bonds mature, borrowing costs could rise. Moreover, some critics worry that large Fed purchases of government debt blur the lines between fiscal and monetary policy, potentially making it easier for the government to run deficits (a phenomenon sometimes termed “debt monetization”). The Fed aims to avoid this by maintaining independence and focusing on inflation/employment mandates. Still, the interplay between the Fed’s balance sheet and Treasury’s financing needs will be a key factor to watch in coming years.

- High Debt Burden and Flexibility: Regardless of who holds the debt, the sheer size of the debt (now about 98% of GDP and rising) poses risks. A diverse investor base (domestic and foreign) has so far absorbed U.S. issuance without disruption, but high and rising debt could lead investors to demand higher interest rates in the future. If a larger share of debt ends up in shorter-term hands (like money market funds or foreign central banks that might reduce holdings), the U.S. could face refinancing risks or interest rate volatility. The current ownership mix – with a solid domestic base and broad international participation – is an asset, but it cannot fully shield the U.S. from the consequences of continued debt growth.

In conclusion, America’s debt is owed mostly to Americans themselves, with the Federal Reserve, government trust funds, and domestic investors holding the lion’s share, and about one-quarter owed to foreign creditors. Over time, reliance has shifted more toward domestic sources. Each category of holder has different motivations and potential impacts: foreign holders underscore global confidence in U.S. creditworthiness, yet introduce geopolitical considerations; domestic holders provide stability but can be subject to domestic financial conditions; intragovernmental holdings represent future liabilities for programs like Social Security; and Federal Reserve holdings intertwine debt management with monetary policy.

The sustainability of the debt depends on continued confidence from all these holders. So far, U.S. Treasuries remain in high demand due to their safety and the depth of the market. However, the rising debt burden and its evolving ownership structure will require careful management. Policymakers will need to consider how interest costs (already surging) divert resources from other priorities, how foreign investment trends might change, and how to ensure a broad and stable investor base for U.S. debt. As history shows, the makeup of debt holders can change – but the underlying need for fiscal sustainability remains paramount. Reducing deficits over time could alleviate some of these risks, ensuring that the nation’s debt – whoever holds it – remains manageable and does not undermine economic prosperity or financial stability.

Sources: Official U.S. Treasury data (including the Treasury Bulletin and TIC reports), Federal Reserve releases, Peter G. Peterson Foundation analysis, Reuters, USAFacts, and Congressional research. All data are the latest available as of 2024–2025.